kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Elliptic Functions

Elliptic Functions

30 Jan 2026

Suppose we’re given a circle of radius $r$ and two points in its perimeter, and we want to compute the length of the arc between these points. This can be computed using elementary functions, for example by determining the angle $\theta$ in radians between these two points with respect to the center and then the arc length is $\theta r$.

For ellipses this is not as trivial. In the 18th century, Giulio Fagnano and Leonhard Euler were the first to use integrals to compute the arc length of an ellipse and these became known as elliptic integrals.

Niels Abel and Carl Jacobi studied the inverse of elliptic integrals and later realized they were doubly periodic, that is they have two fundamental periods, as oppose to trigonometric functions line sine that has a single period. Due to this connection double periodic functions became known as elliptic functions.

In this post we’ll study elliptic functions. We’ll start with simply periodic functions, then doubly periodic functions. We’ll spend most of the time studying properties of the periods.

Simply Periodic Functions

As the name suggests, periodic functions are those with image that repeats indefinitely, for example, $\sin z$, which repeats every $2 \pi$, that is $\sin z = \sin (z + 2\pi)$.

More generally, a function $f(z)$ is called periodic if $f(z) = f(z + w)$ for all $z$ in the domain, in which case $w$ is called the period. For this post, we’ll restrict ourselves to meromorphic functions.

If $w$ is the period of a function, that is $f(z) = f(z + w)$, inductively we can conclude that any integral multiple of $w$ is also a period, that is $f(z) = f(z + nw)$. If a period is not an integral multiple of any other period we call it the fundamental period. If a function has only one fundamental period, then $f$ is called simply periodic. For the remainder of the post, when we say periodic, we’ll imply simply periodic.

The function $f(z) = e^{2\pi i z / w}$ is the simplest periodic function and surprisingly, every periodic function can be expressed in terms of this one.

Lemma 1. Let $f(z)$ be a meromorphic function with domain $\Omega$ and period $w$. Then there exists a unique meromorphic function $g$ such that:

\[f(z) = g(e^{2\pi i z / w})\]So every point in the domain of $g$ has a corresponding image. We still need to make sure we can write $f$ as a function of $g$. In particular, since $f$ has period $w$, for any $z$, $f(z) = f(z + w)$, we need to make sure that $g \circ \zeta (z) = g \circ \zeta (z + w)$. Since $\zeta(z)$ also has period $w$, it also holds that $\zeta(z) = \zeta(z + w)$, since it maps to the same point in $\Omega'$, $g(\zeta(z) = g(\zeta(z + w)) = f(z)$, so it's well defined.

So far we've only found that $g$ is a valid mapping from $\Omega'$ to the image of $f$ but didn't prove anything about its properties. We can show it is holomorphic though. Consider the inverse of $\zeta(z)$, which we can obtain by applying the logarithm: $$ z(\zeta) = \frac{w}{2\pi i} \log (\zeta) $$ So we can write: $$ g(\zeta) = f(z(\zeta)) = f \circ z(\zeta) $$ The problem is that the logarithm is a multi-valued function and so is $z(\zeta)$. We need to turn it into a single-valued one by choosing a proper branch. Let $\zeta_0$ be a point in $\Omega'$. Because $\zeta(z)$ is the exponential, it cannot yield a 0, so $\zeta_0 \ne 0$. Consider a neighborhood $U$ of $\zeta_0$ that doesn't include the origin. In this region, we can choose a branch of the logarithm, denoted by $\log_U$ so that $\log_U(\zeta)$, $\zeta \in U$ is single-valued. Now we function $z_U(\zeta)$ in $U$ as: $$ z_U(\zeta) = \frac{w}{2 \pi i} \log_U(\zeta) $$ Since $\log_U$ is holomorphic in $U$, so is $z_U$. The composition of meromorphic/holomorphic functions is meromorphic so $g(\zeta)$ is meromorphic in $U$. There's nothing special in our choice of $\zeta_0$, so this applies to the entire domain $\Omega'$.

Discrete Fourier Series

Let $\Omega’$ be the domain of the function $g(\zeta)$ as defined in Lemma 1. Suppose it contains an annulus $r_1 \lt \abs{\zeta} \lt r_2$ in which $g$ has no poles. We can then express it via its Laurent series at 0 [2] as:

\[g(\zeta) = \sum_{-\infty}^\infty c_n \zeta^n\]which then lets us express $f(z)$ as:

\[f(z) = g \circ \zeta(z) = \sum_{-\infty}^\infty c_n e^{2 \pi i n z / w}\]which is the Fourier series [3].

Properties

We now consider some properties of periodic functions. First, Lemma 2 shows periodic functions are closed under arithmetic operations.

Lemma 2. Let $f$ and $g$ be periodic functions of same period $w$. Then $f \pm g$, $f * g$ and $f / g$ are also periodic with period $w$.

Lemma 3. Let $f$ be a periodic function with period $w$. Then $f’$ is also periodic with period $w$.

Doubly Periodic Functions

As the name suggests doubly periodic functions have two fundamental periods. Doubly periodic functions are also known as elliptic functions, which is the term we’ll use henceforth. Any period $w$ of an elliptic function $f(z)$ can be written as a integral linear combination of any of its fundamental periods, denoted by $w_1$ and $w_2$:

\[w = n_1 w_1 + n_2 w_2\]We define the set of such periods as the period module of $f(z)$, denoted by $M$. Even if we don’t know $w_1$ and $w_2$ explicitly, we can guarantee that any integral linear combination of any other 2 periods in $M$ is also in $M$, as shown in Lemma 4.

Lemma 4. Let $M$ be the period module of $f(z)$ and $u, v$ any periods in $M$. Then any integral linear combination of $u, v$ is also in $M$.

As Lemma 5 shows, we can choose $w_1$ and $w_2$ such that $w_2 / w_1$ is not real, that is it has a non-zero imaginary part.

Lemma 5. Let $M$ be the period module of $f(z)$. Then there exists $w_1, w_2 \in M$ such that for all $w \in M$, $w = n_1 w_1 + n_2 w_2$ and $w_2 / w_1$ is not real.

Let $w_2$ the element with smallest modulus in $M$ that is not an integer multiple of $w_1$. Note that it can have the same modulus as $w_1$. We claim that $r = w_2 / w_1$ is not real. Suppose it is, by the choice of $w_2$ we know $r$ is not an integer, so it can be placed between two integers $$n \lt r \lt n + 1$$ Multiply this by $\abs{w_1}$ to get: $$ n \abs{w_1} \lt r \abs{w_1} \lt n \abs{w_1} + \abs{w_1} $$ subtract $n \abs{w_1}$: $$ 0 \lt (r - n) \abs{w_1} \lt \abs{w_1} $$ Since $r - n \gt 0$, $\abs{r - n} = r - n$ and so $(r - n) \abs{w_1} = \abs{(r - n) w_1}$: $$ 0 \lt \abs{rw_1 - nw_1} \lt \abs{w_1} $$ Since $r = w_2 / w_1$ or $w_2 = r w_1$: $$ 0 \lt \abs{w_2 - n w_1} \lt \abs{w_1} $$ The number $w' = w_2 - n w_1$ is an integral linear combination of $w_1, w_2$ and is hence in $M$, but $\abs{w'} \lt \abs{w_1}$ contradicts our choice of $w_1$, which implies $w_2/w_1$ being real is false.

It remains to show every $w \in M$ can be expressed as $w = n_1 w_1 + n_2 w_2$ for integers $n_1, n_2$. Suppose we want to find $\lambda_1, \lambda_2$ that satisfy: $$ \begin{align} w &= \lambda_1 w_1 + \lambda_2 w_2 \\ \overline{w} &= \lambda_1 \overline{w_1} + \lambda_2 \overline{w_2} \\ \end{align} $$ We claim that the determinant of the coefficients is non-zero, i.e. $w_1\overline{w_2} + \overline{w_1} w_2 \ne 0$. If we denote $w_1 = a_1 + i b_1$ and $w_2 = a_2 + i b_2$ $$ w_1\overline{w_2} + \overline{w_1} w_2 = (a_1 + i b_1)(a_2 - i b_2) + (a_1 - i b_1)(a_2 + i b_2) $$ Multiplying and cancelling terms we get: $$ = 2i (a_2 b_1 - a_1 b_2) $$ If this is 0, then $a_2 b_1 = a_1 b_2$. We know $w_1$ and $w_2$ are non-zero. So if $a_2 = 0$, then $b_2 \ne 0$ and this implies $a_1 = 0$ which means $w_2 / w_1 = b_2 / b_1$, a contradiction. Similar arguments applies if $b_2 = 0$. So we assume these are all non-zero terms and thus we can write: $$ \frac{a_1}{a_2} = \frac{b_1}{b_2} = k $$ Then $w_1 = a_1 + ib_1 = k(a_2 + ib_2) = kw_2$. Then $w_2 / w_1 = k$, which is also a contradiction since $k$ is real. We conlude that the determinant is non-zero and these equations have a unique solution. This other pair of equations $$ \begin{align} w &= \overline{\lambda_1} w_1 + \overline{\lambda_2} w_2 \\ \overline{w} &= \overline{\lambda_1} \overline{w_1} + \overline{\lambda_2} \overline{w_2} \\ \end{align} $$ also have a non-zero determinant and thus also have a unique solution. The only way this can be true is if $\lambda_1 = \overline{\lambda_1}$ and $\lambda_2 = \overline{\lambda_2}$ which implies both are real. So far we showed any complex number can be expressed as a linear combination of $w_1, w_2$ using real coefficients.

We wish to show that any period in $M$ can be expressed as an integral linear combination of $w_1$ and $w_2$. We'll do that by assuming it's not, and get to a contradiction. Start by assuming that either $\lambda_1$ or $\lambda_2$ is not an integer. Let $m_1$ and $m_2$ be the closest integers to $\lambda_1, \lambda_2$ that is: $$ (5.1) \quad \begin{align} \abs{\lambda_1 - m_1} & \le 1/2 \\ \abs{\lambda_2 - m_2} & \le 1/2 \\ \end{align} $$ Since $m_1, m_2$ are integers, $u = m_1 w_1 + m_2 w_2$ is in $M$ and since we're assuming either $\lambda_1$ and/or $\lambda_2$ are not integers, then $u \ne w$. By Lemma 4, any integer linear combination of $u$ and $w$ is also in $M$, in particular $v = w - u$. We now claim that $\abs{v} \lt \abs{w_2}$. To see why, expand $v$: $$ v = w - m_1 w_1 - m_2 w_2 $$ Since any complex number can be expressed as a linear combination of $w_1, w_2$ using real coefficients, $w = \lambda_1 w_1 + \lambda_2 w_2$: $$ v = (\lambda_1 - m_1) w_1 - (\lambda_2 - m_2) w_2 $$ considering the modulus: $$ \abs{v} = \abs{(\lambda_1 - m_1) w_1 - (\lambda_2 - m_2) w_2} = \abs{(\lambda_1 - m_1) w_1 + (m_2 - \lambda_2) w_2} $$ Because $w_2 / w_1$ is not real, then $\abs{(\lambda_1 - m_1) w_1 / (m_2 - \lambda_2) w_2}$ is also not real. We can thus use the strict triangle inequality [4], i.e. $$ \abs{(\lambda_1 - m_1) w_1 - (m_2 - \lambda_2) w_2} \lt \abs{(\lambda_1 - m_1) w_1} + \abs{(m_2 - \lambda_2) w_2} $$ and obtain: $$ \abs{v} \lt \abs{(\lambda_1 - m_1) w_1} + \abs{(m_2 - \lambda_2) w_2} = \abs{(\lambda_1 - m_1)}\abs{w_1} + \abs{(\lambda_2 - m_2)}\abs{w_2} $$ by our choice of $m_1, m_2$ we can use $(5.1)$: $$ \abs{v} \lt \frac{1}{2}\abs{w_1} + \frac{1}{2}\abs{w_2} $$ since $\abs{w_1} \le \abs{w_2}$: $$ \abs{v} \lt \abs{w_2} $$ the only way this can be true is if $v$ is an integer multiple of $w_1$, because otherwise we'd have picked $w_2 = v$. In that case $\lambda_2 = m_2$ and $\lambda_1 - m_1$ is integer, implying both $\lambda_1, \lambda_2$ are integers, a contradiction. This means $\lambda_1, \lambda_2$ are integers and thus every $w \in M$ is a integral linear combination of $w_1$ and $w_2$.

Any pair of periods that satisfy Lemma 5 will be defined as a base for the module period.

Unimodular Transformations

Suppose we have a base $(w_1, w_2)$ and we want to perform a change of base to $(w’_1, w’_2)$. Since both are in $M$, each can be expressed as an integer linear combination of $(w_1, w_2)$:

\[\begin{align} w'_1 &= a w_1 + b w_2 \\ w'_2 &= c w_1 + d w_2 \end{align}\]In matricial form it becomes:

\[\left[ {\begin{array}{c} w_1' \\ w_2' \\ \end{array} } \right] = \left[ {\begin{array}{cc} a & b \\ c & d \\ \end{array} } \right] \left[ {\begin{array}{c} w_1 \\ w_2 \\ \end{array} } \right]\]So we can convert from one base to another via a transformation represented by an integer matrix. A unimodular matrix is one where the determinant has modulus 1. Lemma 6 shows that the base transformation is a unimodular matrix.

Lemma 6. Let $(w_1, w_2)$ and $(w’_1, w’_2)$ be two basis. Let $T$ be the transformation that takes $(w_1, w_2)$ to $(w’_1, w’_2)$. Then $T$ is unimodular.

We can express the ratio of two bases as:

\[r' = \frac{w'_1}{w'_2} = \frac{aw_1 + bw_2}{c w_1 + dw_2}\]Dividing both sides of the fraction by $w_2$:

\[(1) \quad r' = \frac{a r + b}{cr + d}\]and from Lemma 6, we have $\abs{ad - bc} = 1$.

Canonical Basis

So far we’ve seen there can be multiple basis for a given period module. However, if we restrict the domain of the ratio $r = w_2/w_1$ for the basis, we can make sure it’s unique. The region we’re interested in is defined by the following constraints:

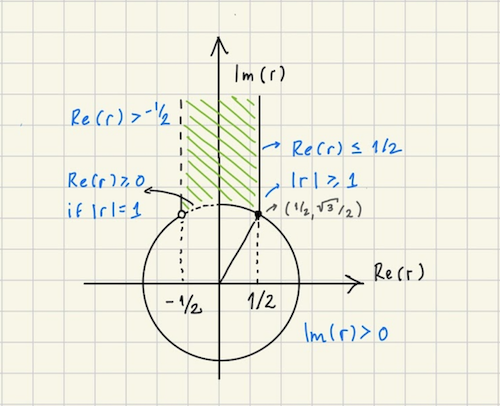

\[\begin{array}{ll} (i) & \Im(r) \gt 0 \\ (ii) & -1/2 \lt \Re(r) \le 1/2 \\ (iii) & \abs{r} \ge 1 \\ (iv) & \Re(r) \ge 0 \quad \mbox{if} \abs{r} = 1 \end{array}\]We call it the fundamental region and depicted it in Figure 1. Our first result is to show a base exists in it, as shown in Lemma 7.

Lemma 7. There exists a base $(w_1, w_2)$ for a period module with $r = w_2/w_1$ in the fundamental region.

We proceed to property $(ii)$. We already know that $\Im(r) \ne 0$ from Lemma 5. If it is negative, we can choose the base $(-w_1, w_2)$. The new ratio is $r' = -w_1/w_2 = -r$, and since $\Im(-r) = -\Im(r)$, it guarantees $\Im (r') \gt 0$, so $(i)$ is satisfied. Property $(iii)$ hasn't been violated because because $r' = -r$ then $\abs{r'} = \abs{r}$ .

We now proceed to property $(iv)$. Assume $\abs{r} = 1$, so that $\abs{w_1} = \abs{w_2}$. If $\Re(r) \lt 0$, we can replace it by $(-w_2, w_1)$. Note that because $\abs{w_1} = \abs{w_2}$ is consistent with the process for picking a base in Lemma 5. Then the new ratio is $r' = -w_1/w_2 = -1/r$. We have $\Im(r') = \Im(-1/r) = -\Im(1/r) = \Im(r)$ and $\Re(r') = \Re(-1/r) = -\Re(1/r) = -\Re(r)$. So if $\Re(r) \lt 0$, then $\Re(r') \gt 0$. It remains to show this change doesn't violate the conditions $(ii)$ or $(iii)$: $\abs{r'} = \abs{r} = 1$, which satisfies $(iii)$. If $\Im(r) \gt 0$ so is $\Im(r')$ which satisfies $(ii)$.

We finally proceed to property $(ii)$. We have that $\abs{w_2} \le \abs{w_1 \pm w_2}$, because otherwise $w_1 \pm w_2$ belongs to period module $M$ spanned by $(w_1, w_2)$ and thus we'd have picked $w_3 = w_1 \pm w_2$ instead of $w_2$. We claim that $\abs{\Re(r)} \le 1/2$. We have $w_2 = w_1 r$, so $\abs{w_2} = \abs{w_1} \abs{r}$. We also have $$ \abs{w_2 \pm w_1} = \abs{w_1 r \pm w_1} = \abs{w_1 (r \pm 1)} = \abs{w_1} \abs{r \pm 1} $$ Since $\abs{w_2} \le \abs{w_1 \pm w_2}$, $$ \abs{w_2} \le \abs{w_1} \abs{r \pm 1} $$ Replacing $\abs{w_2} = \abs{w_1} \abs{r}$, $$ \abs{w_1} \abs{r} \le \abs{w_1} \abs{r \pm 1} $$ Since $w_1$ is non-zero we get: $$ \abs{r} \le \abs{r \pm 1} $$ Square both sides and use $\abs{z}^2 = z \overline{z}$: $$ \abs{r}^2 \le \abs{r \pm 1}^2 = (r \pm 1)(\overline{r \pm 1}) = (r \pm 1)(\overline{r} \pm 1) = r \overline{r} \pm r \pm \overline{r} + 1 = \abs{r}^2 \pm (r + \overline{r}) + 1 $$ Subtracting $\abs{r}^2$ from both sides and using $z + \overline{z} = 2 \Re(z)$: $$ 0 \le \pm 2 \Re(r) + 1 $$ which gives us $\Re(r) \ge -1/2$ and $-\Re(r) \ge -1/2$ which is $\Re(r) \le 1/2$. It almost matches property $(ii)$, except that we require $\Re (r) \ne -1/2$. If that's the case, then $\abs{r} = \abs{r + 1}$ or $\abs{w_2} = \abs{w_1 + w_2}$. If $w_3 = w_1 + w_2$ then $w_3$ is a candidate for $w_2$ consistent with the process from Lemma 5. The new ratio is $r' = (w_1 + w_2) / w_1 = 1 + r$, and thus $\Re(r') = \Re(r) + 1 = 1/2$, so we satisfy $(ii)$ with this tweak. We need to make sure this doesn't violate properties $(i), (iii)$ or $(iv)$. Since $\abs{r'} = \abs{r + 1} = \abs{r}$, condition $(iii)$ is still satisfied. Since $r' = r + 1$, $\Im(r') = \Im(r)$ and property $(i)$ is satisfied. If $\abs{r} = 1$ and $\Re(r) \ge 0$, then we don't need any tweaks because we know already that $\Re (r) \ne -1/2$.

Now that we know such a base always exists, Lemma 8 shows its ratio is unique.

Lemma 8. Let $(w_1, w_2)$ be a base for a period module with $r = w_2/w_1$ in the fundamental region, then $r$ is unique.

$$ r' = \frac{ar + b}{cr + d} = \frac{ar}{d} + \frac{b}{d} = r \pm b $$ Since $b$ is real, $\Re(r') = \Re(r) \pm b$ or $\abs{b} = \abs{\Re(r') - \Re(r)}$. The maximum value the right hand side can assume is less than one, because $-1/2 \lt \Re(r'), \Re(r) \le 1/2$. Since $b$ is integer, it must be 0. Thus $r = r'$.

This was for the case where $c = 0$. Now assume $c \ne 0$. Thus we can divide $(8.3)$ by $\abs{c}$: $$\frac{\abs{cr + d}}{\abs{c}} \le \frac{1}{\abs{c}}$$ since division is closed under modulus: $$\abs{\frac{cr + d}{c}} = \abs{r + \frac{d}{c}} \le \frac{1}{\abs{c}}$$ in the complex plan, this equation corresponds to a circle of radius $1/\abs{c}$ centered at the point $d/c$ in the real line. If $\abs{c} \ge 2$, this implies that $\Im(r) \le 1/2$. However, the smallest value of $\Im(r)$ is attained when $\Re(r) = 1/2$, for which case $\Im(r) = \sqrt{3}/2$ (this is easier to visualizer in Figure 1 of the fundamental region), so this cannot happen and thus $\abs{c} \le 1$ and since $c \ne 0$, $\abs{c} = 1$.

If $\abs{c} = 1$, $(8.3)$ becomes $\abs{r \pm d} \le 1$. Since $\abs{z} \ge \abs{\Re(z)}$, then $\abs{\Re(r) \pm d} \le \abs{r \pm d} \le 1$. Since $\abs{\Re(r)} \le 1/2$, $d$ cannot be too large. If $\abs{d} \ge 2$, then $\abs{r \pm d} \gt 1$ a contradiction, so $d \in \curly{-1, 0, 1}$.

Now suppose $d = 1$. Then $(8.3)$ becomes $\abs{r + 1} \le 1$ which is the unit circle centered in $(-1, 0)$. The intersection between this circle and the unit circumference at the origin is a single point is $(-1/2, \sqrt{3}/2)$. However this point does not belong to the fundamental region (this is easier to visualizer in Figure 1 of the fundamental region). Thus $d \ne -1$.

Now suppose $d = -1$. Then $(8.3)$ becomes $\abs{r - 1} \le 1$ which is the unit circle centered in $(1, 0)$. The intersection between this circle and the unit circumference at the origin is a single point is $r = (1/2, \sqrt{3}/2)$ which does belong to the fundamental region. But since this point is on the circumference of $\abs{r - 1} \le 1$, we have the equality $\abs{r - 1} = 1$, which implies $\abs{cr + d}^2 = 1$ and thus $\Im(r') = \Im(r)$, and thus $\Im(r') = \sqrt{3}/2$ but there's a single point with this image in the fundamental region and thus $r = r'$.

Finally suppose $d = 0$. Then $(8.3)$ becomes $\abs{r} \le 1$. Since $\abs{r} \ge 1$ in the fundamental region, $\abs{r} = 1$. From $(8.2)$ we get $bc = -1$. Since $\abs{c} = 1$, $\abs{b} = 1$ and they have opposite signs. From $(1)$ we get: $$r' = \frac{ar + b}{cr} = \frac{a}{c} + \frac{b}{cr} = \pm a - 1/r$$ Since $\abs{r} = 1$, $\abs{r}^2 = r \overline{r} = 1$ and $\overline{r} = 1/r$, so $$r' = \pm a - \overline{r}$$ or $$r' + \overline{r} = \pm a$$ Since $a$ is real, the imaginary parts of $r'$ and $r$ cancel out and $\Im(r') = \Im(r)$. We also have that $$\Re(r') + \Re(\overline{r}) = \Re(r') + \Re(r) = \pm a$$ Since $-1/2 \lt Re(r'), Re(r) \le 1/2$, their sum is at most $1$ and never $-1$, so $a \in \curly{0, 1}$. If $a = 1$, then it must be that $Re(r) = Re(r') = 1/2$. Since $\Im(r') = \Im(r)$, $r' = r$. Now if $a = 0$, $r' = -\overline{r}$ so $\Re(r') = -\Re(r)$. However, since $\abs{r} = 1$ and $\abs{r'} = 1$, property $(iv)$ tells us $\Re(r'), \Re(r) \ge 0$, so it must be that $\Re(r') = \Re(r) = 0$. In this case $\Im(r') = \Im(r) = 1$ and $r' = r$.

So we proved that no matter which valid combination of $a, b, c$ and $d$, we end up with $r' = r$.

we define any base $(w_1, w_2)$ with $r = w_2 / w_1$ in the fundamental region as a canonical basis. Note that these are not unique given $(-w_1, -w_2)$ is a base with ratio $r$.

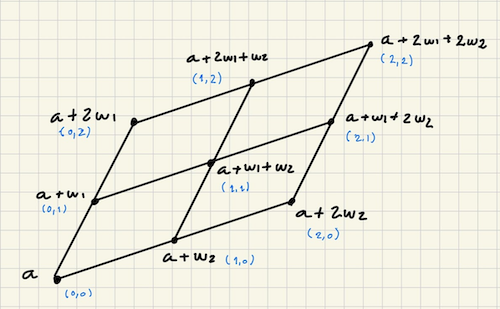

Lattice

Any base $(w_1, w_2)$ of the module period induces a lattice. The points on this lattice are those of the form $n_1 w_1 + n_2 w_2$. Each “cell” on this lattice is a parallelogram formed by adjacent points $(n_1 w_1, n_2 w_2)$, $((n_1 + 1) w_1, n_2 w_2)$, $(n_1 w_1, (n_2 + 1) w_2)$, $((n_1 + 1) w_1, (n_2 + 1) w_2)$.

The property of elliptic functions is that for any $a$, $f(a) = f(a + n_1 w_1 + n_2 w_2)$, so for any two points in different parallelograms in the same relative position within their respective parallelograms have the same value. Thus, an elliptic function is fully specified for the entire complex plane just from a single parallelogram.

Congruence Classes

We say that $z_1$ is congruent to $z_2$ with respect to $M$, denoted by $z_1 \equiv z_2 \pmod M$, if the difference $z_1 - z_2$ belongs to $M$. This induces congruence classes, and for $z_1, z_2$ on the same class $f(z_1) = f(z_2)$.

Properties

We now consider some properties of elliptic functions. Lemma 2 and Lemma 3 apply to elliptic function since they’re doubly periodic and satisfy:

\[f(z) = f(z + w_1) \quad \mbox{and} \quad f(z) = f(z + w_2)\]By definition elliptic functions are meromorphic. If they have no poles then they’re holomorphics. Since $f$ is fully specified from a single parallelogram, its value is bounded in this finite region. According to Liouville’s theorem, a bounded holomorphic function must be constant.

Corollary 9. An elliptic function without poles is a constant.

If a function does have poles, Lemma 10 shows the sum of their residues is 0.

Lemma 10. The sum of residues of an elliptic function is 0.

Because simple poles (poles of order 1) have non-zero residue, it means that a non-constant elliptic function cannot have a single simple pole.

Lemma 11. A non-constant elliptic function has equally many poles as it has zeros.

An interesting consequence of Lemma 11 is the following. Suppose $f(z)$ has $N$ poles. If $p$ is a pole of $f(z)$, then $p$ is also a pole of $f(z) - c$ because if $1/f(p) = 0$ then $1/(f(p) - c) = 0$. From Lemma 11, $f(z) - c$ has the same number of zeros as $f(z)$, so there are $N$ values of $z$ which makes $f(z) = c$. Note that it doesn’t mean that the number of distinct zeros are the same for all $c$, since $N$ accounts for the multiplicity of zeros. The value $N$ is also known as the order of $f$.

In Alfhor’s [1] he claims that the order is the number of incongruent roots of the equation $f(z) = c$. This seems to imply it’s the same no matter $c$ and equals to $N$, but I don’t understand why this is true.

Theorem 12. Let $a_1, \dots, a_n$ be the zeros and $b_1, \dots, b_n$ be the poles of an elliptic function $f$ with module period $M$. Then

\[a_1 + \dots + a_n \equiv b_1 + \dots + b_n \pmod M\]Conclusion

Elliptic functions are pretty interesting! I found the name pretty deceptive and more complicated-sounding than it actually is. I much prefer the term doubly-periodic functions.

I’m starting to see why elliptic functions appear in number theory, given that a lot of the results around the period module guarantee that the results are integers. This connection is fascinating!

Appendix

Lemma 13. Let $M$ be the period module of an elliptic function $f(z)$. There are either 2, 4, and 6 points in $M$ that are the closest to the origin.

Suppose there exists another $w_2$ which is not an integral multiple of $w_1$ but with $\abs{w_2} = r$. Let's consider the square of the module of their difference, $\abs{w_1 - w_2}^2$. By the law of cosines: $$ \abs{w_1 - w_2}^2 = \abs{w_1}^2 + \abs{w_2}^2 - 2\abs{w_1}\abs{w_2} \cos \theta $$ where we can interpret the $\theta$ is the angle between the vectors. Replacing with $r$: $$ \abs{w_1 - w_2}^2 = 2r^2 + - 2r^2 \cos \theta = 2r^2(1 - \cos \theta) $$ If $\theta \lt 60^o$, then $\cos \theta \gt 1/2$, which would imply: $$ \abs{w_1 - w_2}^2 = 2r^2(1 - \cos \theta) \lt 2r^2(1 - 1/2) = r^2 $$ So the point $w' = w_1 - w_2$ would have a modulus smaller than $r$, a contradiction. If the points in the circumference of radius $r$ must be $60^o$ appart, the maximum number of points we can "fit" in it. This leads us to 2, 4 and 6 possibilities.

Related Posts

Totally Unimodular Matrices. I was initially surprised to see totally unimodular matrices mentioned in the context of elliptic functions. I had studied them in the context of integer linear programming, but in hindsight it makes sense. There seems to be a deep connection between elliptic functions and integers and mentioned in the conclusion.