kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Totally Unimodular Matrices

Totally Unimodular Matrices

02 Sep 2012

In this post we study totally unimodular matrices. We’ll start with their definition and understand their importance by covering different equivalences between them and problems in combinatorial optimization.

We then show some properties specific to totally unimodular matrices and finish with some examples.

Motivation

Sometime ago, we said that problems such as the minimum path, maximum flow and minimum cost max flow can be modeled using linear programming with the interesting property that the optimal solutions are always integral.

In that post, we also said that it was because the coefficient matrix of the constraints of the formulations are totally unimodular. In this post we’ll prove this result.

Since linear programming algorithms work by visiting vertices of its polyhedra, this implies that integer solutions of linear programs with constraints corresponding to a totally unimodular matrix can be found in polynomial time.

In other words, if you can model a problem as a linear program satisfying the totally unimodular matrix constraint, then your problem is proven to be in $\mathbf{P}$.

Definition

An unimodular matrix is a square matrix with integer entries such that its determinant is either $-1$, $0$ or $1$. A matrix is said totally unimodular (TU for short) if all its square submatrices are unimodular. Note that a totally unimodular matrix is not necessarily square and hence not necessarily unimodular!

Properties

Let $A$ be a totally unimodular matrix with dimensions $n \times m$. Then we have the following properties:

Lemma 1. All elements in $A$ are either $0$, $1$ or $-1$.

Lemma 2. Its transpose, $A^{T}$, is TU.

Lemma 3. Let $B$ obtained by appending a column vector ($n \times 1$) with at most 1 non-zero entry to $A$. Then $B$ is TU.

Otherwise there's exactly one entry equal to 1, say at row $k$. We can use Laplace's expansion along the last column of $B'$, $m + 1$. Then we can claim that: $$\det(B') = (-1)^{k + m + 1} \det(B'_{k,m+1}$$ Where $B'_{k,m+1}$ is the matrix $B'$ without the last column and the row $k$. This (square) submatrix is definetely a submatrix of $A$ so its determinant is in $\curly{-1, 0, 1}$, so we conclude $\det(B')$ is also in $\curly{-1, 0, 1}$ and thus $B'$ is unimodular.

Since this applies to any square submatrix of $B$, $B$ is TU.

A corollary of this property is that appending the identity matrix $n \times n$ to the right of $A$ preserves TU.

Another corollary is that appending rows with at most one non-zero entry also preserves TU by combinig Property 3 and Property 2 (transposition).

Lemma 4. Any submatrix of $A$ is TU.

Lemma 5. The matrix obtained by multiplying any row of $A$ by $-1$ is TU.

We can use Laplace's expansion along such row $k'$ of $B'$: $$ \det(B') = \sum_{j = 1}^m 1^{k' + j} b'_{k', j} \det(B'_{k', j}) $$ Where $b'_{k', j}$ is the entry at row $k'$ and column $j$ of $B'$ and $B'_{k', j}$ is the matrix $B'$ without row $k'$ and column $j$. Because $B'_{k', j}$ does not contain $k'$, it's the same as $A'_{k', j}$.

Also $b'_{k',j} = - a'_{k',j}$, which gives us: $$ \det(B') = - \sum_{j = 1}^m 1^{k' + j} a'_{k', j} \det(A'_{k', j}) = -\det(A') $$ Since $\det(A') \in \curly{-1, 0, 1}$, so is $\det(B')$.

By combining Property 5 and Property 2 (transposition) we get the corollary that multiplying any column of $A$ by $-1$ also preserves TU.

Lemma 6. The permutation of rows or column preserves TU.

Let $1 \le i \le n - 1$ be a row of $A$ and $B$ the result of swapping rows $i$ and $i + 1$. Now consider a square submatrix $B'$ of $B$. If $B'$ doesn't intercept row $i$ nor $i + 1$, then it's not affected by the swap and it exists as a square submatrix of $A$ and is thus unimodular.

If $B'$ intercepts only $i$ then it must be its first row. Let the set of rows of $B'$ be denoted as $r_1, r_2, \cdots, r_k$ with $r_1 = i$ and columns $c_1, c_2, \cdots, c_k$. There should be a square submatrix $A'$ of $A$ with rows $i, i + 1, r_2, \dots, r_k$ and columns equal to $B'$'s except for an extra column $c'$, i.e. $c_1, c_2, \cdots, c', \cdots, c_k$. Then the submatrix obtained by removing row $i + 1$ and column $c'$ is also a square submatrix of $A$ and is equal to $B'$ which is thus unimodular. A similar argument holds if $B'$ intercepts only $i + 1$.

Otherwise $B'$ intercepts both $i$ and $i+1$ and they're also adjacent in it. Let $B'$ rows be denoted by $r_1, r_2, \cdots, r_{i'}, r_{i'+1} \cdots, r_k$, where $r_{i'} = i + 1$ and $r_{i' + 1} = i$. There's a square submatrix $A'$ of $A$ which is similar to $B'$ except that rows $i$ are swapped, that is, its columns are $r_1, r_2, \cdots, r_{i' + 1}, r_{i'} \cdots, r_k$. We can define $B'$'s determinant via Laplace's expansion along its row $i'$-th row: $$ \det(B') = \sum_{j = 1}^{k} (-1)^{i' + j} b'_{i',j} \det(B'_{i'j}) $$ We define $A'$'s determinant along its $i'+1$-th row: $$ \det(A') = \sum_{j = 1}^{k} (-1)^{i' + 1 + j} a'_{i'+1,j}\det(A'_{i' + 1,j}) $$ Now, because $A'$'s $i'+1$-th row is $B'$'s $i'$-th row, we have $a'_{i'+1,j} = b'_{i',j}$ and removing that row leads to the same submatrix, so $A'_{i' + 1,j} = B'_{i'j}$. Also $(-1)^{i' + 1 + j} = (-1)(-1)^{i' + j}$ thus we have: $$ \det(A') = \sum_{j = 1}^{k} (-1)(-1)^{i' + j} b'_{i',j}\det(B'_{i' + 1,j}) = -\det(B') $$ Since $\det(A') \in \curly{-1, 0, 1}$, so is $\det(B')$ and $B'$ is unimodular. We just showed that all square submatrices of $B$ are unimodular and thus $B$ is TU.

Combining this property with Property 3 enables us to insert a column or row with at most one non-zero entries anywhere in the matrix and preserve TU.

Lemma 7. The matrix obtained by duplicating any row or column of $A$ is TU

When it intercepts both $i$ and $i + 1$, $B'$ has duplicate rows and it can be shown that its determinant must be $0$ because these are linearly depended rows. For duplicate rows in particular we can use Laplace's expansion to show that $\det(B') = -\det(B')$, which leds to the same conclusion. Anyway, $B'$ is also unimodular and hence $B$ is TU.

By utilizing Property 6 we can show that the duplicated row $i$ can be inserted anywhere, not just at position $i + 1$. Further by leveraging transposition, Property 7,

Operations on TUs

Given TU matrices $A$ and $B$, the following operations preserve TU.

Lemma 9. 1-sum:

\[A \oplus_1 B := \left[ \begin{array}{rr} A & 0\\ 0 & B\\ \end{array} \right]\]We can use the equivalence between TU $(i)$ and $(iii)$, described in the section Equivalences. We first observe that $A' = \left[ \begin{array}{c} A \\0 \end{array} \right]$ is TU and so is $B' = \left[ \begin{array}{c} 0 \\B \end{array} \right]$.

So we have that $M = [A' \mid B']$. Let $C$ any subset of columns of $M$. Let $C_A$ be the columns intersecting $A'$ and $C_B$ those intersecting $B'$. We know that $S(C_A)$ is unimodular and so is $S(C_B)$.

Now we consider the partition of $C$ into $C_+ = C_{A+} \cup C_{B+}$ and $C_- = C_{A-} \cup C_{B-}$. We claim that $S(C)$ is unimodular. Let $v = S(C)$ and $v_i$ one of its elements for the $i$-th row.

If $i$ intersects the top of $M$, i.e. $[A 0]$, $v_i$ can be written as: $$v_i = \sum_{j \in C_{A+}} a_{ij} - \sum_{j \in C_{A-}} a_{ij}$$ No terms from $C_{B+}$ and $C_{B-}$ appear because they're zero. And since $A'$ is TU, $S(A')$ is unimodular and hence $v_i$ is also unimodular. If $i$ intersects the bottom of $M$, $[0 B]$, we can arrive to a similar conclusion.

Lemma 10. 2-sum:

Let

\[A' = \left[ \begin{array}{rr} A & a \end{array} \right] \qquad B' = \left[ \begin{array}{c} b \\ B \end{array} \right]\]where $a$ is a column vector and $b$ a row vector. Then

\[A' \oplus_2 B' := \left[ \begin{array}{rr} A & ab\\ 0 & B\\ \end{array} \right]\]is TU.

Case 1. Row $i$ intersects $[0 \mid B]$. Then we're done, because $[0 \mid B]$ is TU.

Case 2. Row $i$ intersects $[A \mid ab]$, we can express $v_i$ as: $$v_i = \sum_{j \in C_{X+}} a_{ij} - \sum_{j \in C_{X-}} a_{ij} + \sum_{j \in C_{Y+}} a_i b_j - \sum_{j \in C_{Y-}} a_i b_j$$ Where $a_{ij}$ is an entry in $A$, $a_i$ in $a$, and $b_j$ in $b$. Moving $a_i$ out of the sums: $$= \sum_{j \in C_{X+}} a_{ij} - \sum_{j \in C_{X-}} a_{ij} + a_i(\sum_{j \in C_{Y+}} b_j - \sum_{j \in C_{Y-}} b_j)$$ Since $Y$ is TU, $S(Y)$ is unimodular and thus $$\delta = \sum_{j \in C_{Y+}} b_j - \sum_{j \in C_{Y-}} b_j$$ is also unimodular. Note that $\delta$ doesn't depend on $i$, just on the choice of columns $C_{Y+}$ and $C_{Y-}$. So we have: $$(10.1) = a_i \delta + \sum_{j \in C_{X+}} a_{ij} - \sum_{j \in C_{X-}} a_{ij}$$ With $\delta \in \curly{-1, 0, 1}$. If $\delta = 0$, it is as if $C_{Y+}$ and $C_{Y-}$ were empty, which reduces to the case where $C$ only intersects $A$. Since $A$ is TU, we're done.

Otherwise, consider the set of columns $C_{X'} = C_{X} \cup \curly{a}$. Since this is a subset of $[A \mid a]$, which is TU, $S(C_{X'})$ is unimodular, with column $a$ belonging to either $C_{X'+}$ or $C_{X'-}$. If it's the latter, we can swap the partitions which would have the result of multiplying $S(C_{X'})$ by $-1$ but doesn't change its unimodularity, so assume $a$ is in $C_{X'+}$. Let $u = S(C_{X'})$. For the $i$-th row we have: $$u_i = a_i + \sum_{j \in C_{X+}} a_{ij} - \sum_{j \in C_{X-}} a_{ij}$$ Similarly, suppose $\delta = -1$. We can swap $C_{Y+}$ and $C_{Y-}$ which would have the effect of multiplying $S(Y)$ by $-1$, including $\delta$. So we can assume $\delta = 1$ (note this doesn't invalidate Case 1). So $(10.1)$ becomes: $$(10.1) = a_i + \sum_{j \in C_{X+}} a_{ij} - \sum_{j \in C_{X-}} a_{ij}$$ Which is exactly $u_i$, which is unimodular. So $v = S(C)$ is unimodular and $M$ is TU.

A parting note is that our choice of partition cannot be coupled with any one specific row $i$, since the partition is applied across all rows, equally. QED.

Lemma 11 3-sum:

\[\left[ \begin{array}{rrr} A & a & a\\ c & 0 & 1\\ \end{array} \right] \oplus_3 \left[ \begin{array}{rrr} 1 & 0 & b\\ d & d & B\\ \end{array} \right] := \left[ \begin{array}{rr} A & ab\\ dc & B\\ \end{array} \right]\]where $a$, $d$ are column vectors and $b$, $c$ are row vectors. The 0 and 1 are scalars (i.e. do not denote a matrix of 0s and 1s).

Case 1. Row $i$ intersects $A$ and $ab$, in which case $v_i$ is: $$v_i = \sum_{j \in C_{X+}} a_{ij} - \sum_{j \in C_{X-}} a_{ij} + \sum_{j \in C_{Y+}} a_i b_j - \sum_{j \in C_{Y-}} a_i b_j$$ Which is exactly as in Lemma 10. Isolating $a_i$ and noticing the sums of $b_j$ do not depend on the row, so it's a constant $\delta$ with a fixed choice of partition, we have: $$v_i = \delta a_i + \sum_{j \in C_{X+}} a_{ij} - \sum_{j \in C_{X-}} a_{ij}$$ With $$\delta = \sum_{j \in C_{Y+}} b_j - \sum_{j \in C_{Y-}} b_j$$ Consider the following matrix $$ \left[ \begin{array}{rr} 0 & b\\ d & B\\ \end{array} \right] $$ which is TU. Let $C_{Y'} = C_Y \cup \curly{d}$. There's a partition $C_{Y'+}, C_{Y'-}$ for which $S(C_{Y'})$ is unimodular. We want column $d$ to belong to $C_{Y'-}$. If it does not, we swap $C_{Y'+}$ and $C_{Y'-}$. The first row of $S(C_{Y'})$ is exactly $\delta$ and it's unimodular, so $\delta \in \curly{-1, 0, 1}$.

If $\delta = 0$, then $S(C_X)$ is unimodular because $A$ is TU and we're done. Assume $\delta \ne 0$. Like before, we note that the matrix $$ \left[ \begin{array}{rr} A & a\\ c & 0\\ \end{array} \right] $$ is TU. Let $C_{X'} = C_X \cup \curly{a}$. Since the matrix is TU, $S(C_{X'})$ is unimodular for partitions $C_{X'+}$ and $C_{X'-}$. As before, we can swap partitions to make sure that $a$ belongs to $C_{X'+}$, so that the ssum: $$a_i + \sum_{j \in C_{X'+}} a_{ij} - \sum_{j \in C_{X'-}} a_{ij}$$ is unimodular. If $\delta = 1$, we can set $C_{X+} = C_{X'+}$ and $C_{X-} = C_{X'-}$ and we're done. If $\delta = -1$, we cannot freely manipulate the sign of $\delta$ like in Lemma 10 since it affects Case 2 in this case.

However, we have that this matrix is TU: $$ \left[ \begin{array}{rr} 1 & b\\ d & B\\ \end{array} \right] $$ Let $C_{Y''} = C_Y \cup \curly{d}$ and let $(C_{Y''+}, C_{Y''-})$ be a partition such that $w' = S(C_{Y''})$ is unimodular for this matrix. The first element is given by: $${w'}_1 = \pm 1 + \sum_{j \in C_{Y''+}} b_j - \sum_{j \in C_{Y''-}} b_j$$ The $\pm$ depends on whether we include the column $1 / d$ in the positive or the negative partition. Let's make sure it's on the negative partition (by appropriate swapping) and since ${w'}_1$ is unimodular, we can set $C_{Y+} = C_{Y''+}$ and $C_{Y-} = C_{Y''-}$ and can conclude that $${w'}_1 = -1 + \delta$$ Which forces $\delta$ to not be $-1$, but in this case $\delta$ could be $2$. However, we claim that if $\delta$ in $C_{Y'}$ is odd, then $\delta$ in $C_{Y''}$ is odd too. To avoid confusion let's define: $$\delta' = \sum_{j \in C_{Y'+}} b_j - \sum_{j \in C_{Y'-}} b_j = P' - N'$$ and $$\delta'' = \sum_{j \in C_{Y''+}} b_j) - \sum_{j \in C_{Y''-}} b_j = P'' - N''$$ Since $\delta'$ is odd, exactly one of $P'$ and $N'$ is odd. Without loss of generality, assume $P'$ is. Thus $N'$ is even. We can "convert" the partition $(C_{Y'+}, C_{Y'-})$ into $(C_{Y''+}, C_{Y''-})$ by moving one element at a time from the positive to the negative partitions and vice-versa, because they're the partition of the same set of columns, $C_Y \cup \curly{d}$.

Let's consider the move one column $x$ from/to $C_{Y'+}$ to/from $C_{Y'-}$. If $b_x = 0$, it has no effect in $P'$ nor $N'$ so $\delta'$'s parity is maintained. Suppose $b_x = 1$. Then the effect of moving from $C_{Y'+}$ to $C_{Y'-}$ is that it subtracts $1$ from $P'$ and adds $1$ to $N'$. $P'$ is now even and $N'$ odd, but the parity of $\delta'$ is unchanged. The same logic applies for $b_x = -1$ or moving from $C_{Y'-}$ to $C_{Y'+}$.

Since $\delta' = -1$ at this point, we conclude that $\delta''$ is odd too, and more specifically $1$! So we choose the partition $C_{Y+} = C_{Y''+}$ and $C_{Y-} = C_{Y''-}$ and we're done!

Case 2. Row $i$ intersects $[dc \mid B]$. This is the symmetrical opposite of Case 1. Noting that we're assuming column $\left[ \begin{array}{c} a \\ \curly{0,1} \end{array} \right]$ is in the positive partition and $\left[ \begin{array}{c} \curly{0,1} \\ d \end{array} \right]$ in the negative one, required by Case 1.

Equivalences

There are many different characterizations of totally unimodular matrices. Let $A$ be a matrix with entries in $\curly{-1, 0, 1}$. Then the following are equivalent:

$(i)$ $A$ is totally unimodular.

$(ii)$ If $a, b, c, d$ are integral vectors, the polytope

\[P = \{x \mid a \le Ax \le b; c \le x \le d \}\]has integer vertices.

Let $A$ be a matrix with entries in $\curly{-1, 0, 1}$. We define $A$ as bipartite unimodular if for every subset of columns $C$ of $A$, there is a partition $(C_{+}, C_{-})$ of $C$ such that the sums such that the sum of columns in $C_{+}$ minus those in $C_{-}$ yields a column vector with entries in $\curly{-1, 0, 1}$

$(iii)$ $A$ is bipartite unimodular.

$(iv)$ Each non-singular submatrix of $A$ has a row with an odd number of non-zero elements

$(v)$ The sum of entries in any square submatrix with even row and colum sums is divisible by 4.

$(vi)$ No square submatrix of $A$ has determinant $+2$ or $-2$

To prove these equivalences, we just need to find a cycle involving all these items. We defer to different theorems in the Appendix:

- $(i) \rightarrow (ii)$ - Corollary 16.

- $(ii) \rightarrow (iii)$ - Theorem 17.

- $(iii) \rightarrow (iv)$ - Theorem 18.

- $(iii) \rightarrow (v)$ - TBD.

- $(iv) \rightarrow (vi)$ - TBD.

- $(v) \rightarrow (vi)$ - TBD.

- $(vi) \rightarrow (i)$ - TBD.

One such cycle is (bold denoting unique occurrence):

\[\textbf{(i)} \rightarrow \textbf{(ii)} \rightarrow \textbf{(iii)} \rightarrow \textbf{(iv)} \rightarrow (vi) \\ \rightarrow (i) \rightarrow (ii) \rightarrow (iii) \rightarrow \textbf{(v)} \rightarrow \textbf{(vi)} \rightarrow (i)\]Polytopes

Corollary 12. Let $A$ be a totally unimodular matrix and $P$ the polytope

\[P = \{c^Tx \mid Ax \le b; x \ge 0 \}\]Then its dual,

\[Q = \{b^Ty \mid A^Ty \ge c; y \ge 0\}\]also has integer vertices.

Examples

Bipartite Graphs

Let \(G = (V, E)\) be an undirected graph and \(M\) the incidence matrix of \(G\). That is, a binary matrix where each line corresponds to a vertex \(v\) and each column to an edge \(e\). We have \(M_{v,e} = 1\) if \(v\) is an endpoint of \(e\) or \(M_{v,e} = 0\) otherwise. Then, we have the following result:

Theorem 13. The incidence matrix of a graph \(G\) is totally unimodular if and only if, \(G\) is bipartite.

This result can be used to derive the König-Egerváry theorem, stating that the maximum cardinality matching and the minimum vertex cover have the same value bipartite graphs.

The maximum cardinality can be modeled as integer linear programming:

\[\max \sum_{e \in E} y_e\] \[\begin{array}{llclr} & \sum_{e = (u, v)} y_e & \le & 1 & \forall v \in V\\ & y_e & \in & \{0, 1\} & \forall e \in E \end{array}\]And its dual is the minimum vertex cover:

\[\min \sum_{v \in V} x_v\] \[\begin{array}{llclr} & x_u + x_v & \ge & 1 & \forall (u,v) \in E\\ & x_v & \le & \{0, 1\} & \forall v \in V \end{array}\]It’s not hard to see that if \(M\) is the incidence matrix of the graph, then the problems can be stated as

\[(1) \quad \max \{1y \mid My \le 1; y \mbox{ binary} \}\]and

\[(2) \quad \min \{x1 \mid xM \ge 1; x \mbox{ binary} \}\]If the graph is bipartite, we can use Theorem 2 and the strong duality for linear programs to conclude that $(1) = (2)$.

Directed Graphs

Let \(D = (V, A)\) a directed graph, and \(M\) be the incidence matrix of \(D\). That is, a matrix where each line corresponds to a vertex and each column to an arc. For each arc \(e = (u, v)\), we have \(M_{u, e} = -1\) and \(M_{v, e} = 1\) and 0 otherwise. For directed graphs, we have a even stronger result:

Theorem 14. The incidence matrix of a directed graph \(D\) is totally modular.

Consider a network represented by \(D\) and with capacities represented by \(c : A \rightarrow \mathbb{R}_{+}\). For each directed edge \((ij) \in A\), let \(x_{ij}\) be the flow in this edge.

If \(M\) is the incidence matrix of \(D\), then \(Mx = 0\) corresponds to

\[(3) \quad \sum_{(iv) \in A} x_{iv} = \sum_{(vi) \in A} x_{vi} \qquad \forall v \in V\]which are the flow conservation constraints. Since \(M\) is totally unimodular, then if \(c\) is integer, it’s possible to show that the polytope \(\{x \mid 0 \le x \le c; Mx = 0\}\) has integral vertices. This polytope also represents the constraints of the max circulation problem.

Now, we can use these observations to prove that the following LP formulation for the max-flow problem has an optimal integer solution:

\[\max \sum_{(si) \in A} x_{si}\]Subject to:

\[\begin{array}{llclr} & \sum_{(iv) \in A} x_{iv} & = & \sum_{(vi) \in A} x_{vi} & \forall v \in V \setminus \{s, t\}\\ 0 \le & x_{ij} & \le & c_{ij} & \forall (ij) \in A\\ \end{array}\]We can see that the constraints matrix of the above formulation is a submatrix of the max circulation problem and by Property 3, it’s also TU, which in turn means the corresponding polytope has integral vertices.

Related Posts

Mentioned by Elliptic Functions.

Conclusion

In this post, we introduced the concept of total unimodular matrices and presented two simple examples: the incidence matrix of a bipartite graph and the incidence matrix of a directed graph.

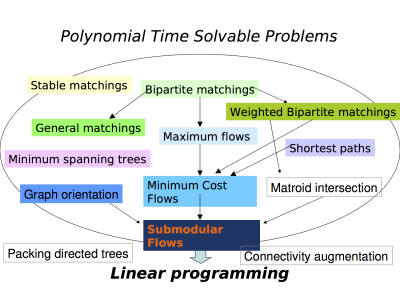

Here’s a cool chart of common polynomial time solvable problems organized by their generality [2].

In future posts, we’ll keep exploring this subject by studying other examples and properties of TU matrices.

Appendix

Theorem 15. Let $A$ be a totally unimodular matrix and $b$ an integer vector. Then the polytope

\[P = \{x \mid Ax \le b \}\]has integer vertices.

Corollary 16. Let $A$ be a totally unimodular matrix and integer vectors of appropriate dimensions $a$, $b$, $c$ and $d$. Then the polytope

\[P = \{x \mid a \le Ax \le b; c \le x \le d \}\]has integer vertices.

Theorem 17. If $A$ is a TU matrix then it is bipartite unimodular.

This polytope is not empty because the vector $x = \frac{1}{2} d$ satisfies all the constraints and is thus an internal point of $P$. Due to $0 \le x \le d$, every integer point in this polytope must be a $\curly{0, 1}$-vector.

Now define the vector $y = d - 2x$. Let's analyze its contents. If $d_j = 0$, then $x_j = 0$, so $y_j = 0$. Now suppose $d_j = 1$. If $x_j = 0$, then $y_j = 1$ and if $x_j = 1$, then $y_j = -1$. We can interpret $y$ as follows: if $y_j = 1$, then $j$ is a column in $C_{+}$ and if $y_j = -1$, then $j$ is a column in $C_{-}$. Thus $Ay$ represents the sum of columns in $C_{+}$ minus the sum of columns in $C_{-}$, exactly the thing the theorem wants to calculate. It remains to prove that $Ay$ only contains entries in $\curly{-1, 0, 1}$.

Let's define $u = Ax$ and $w = Ay$. From the constraints we have that the $i$-th element of $u$ is subject to: $$(17.1) \left\lfloor \frac{1}{2} v_i \right\rfloor \le u_i \le \left\lceil \frac{1}{2} v_i \right\rceil$$ We can write the $w$ as a function of $u$ and $v$, since $Ay = Ad - 2Ax$: $$w_i = v_i - 2u_i$$ Multply $(17.1)$ by 2: $$2 \left\lfloor \frac{1}{2} v_i \right\rfloor \le 2 u_i \le 2 \left\lceil \frac{1}{2} v_i \right\rceil$$ if $v_i$ is even, then this equation reduces to $2u_i = v_i$ and $w_i = 0$. If $v_i$ is odd, say $2k + 1$, then $2 \lfloor \frac{1}{2} v_i \rfloor = 2k = v_i - 1$ and $2 \lceil \frac{1}{2} v_i \rceil = 2k + 2 = v_i + 1$, so we get $v_i - 1 \le 2u_i \le v_i + 1$ so $-1 \le w_i \le 1$. Since all elements involved are integers, $u_i$ and $v_i$ are also integers and thus $w_i$. This then proves $Ay$ only contains entries in $\curly{-1, 0, 1}$. QED

Theorem 18. If $A$ is bipartite unimodular, then any nonsingular submatrix of $A$ has at least one row where the number of non-zero entries is odd.

Let $C$ be the columns of $A'$. Since this is a subset of columns of $C$, there's a partition $(C_+, C_-)$ such that the sum of the column vectors in $C_+$ minus those in $C_-$ yields a column vector with entries in $\curly{-1, 0, 1}$. But since the number of non-zero elements on each row is even, the sum must be even too, which can only mean they're all $0$.

Let be a row vector, with $x_j = 1$ if column $j \in C_+$ and $x_j = -1$ if $j \in C_-$. Then we have that $A'x = 0$. Since $x \neq 0$, it implies $A'$ is singular. QED

Theorem 19. If $A$ is bipartite unimodular, then the sum of entries in any square submatrix with even row and colum sums is divisible by 4.

But since we're assuming that the sum is even, it must be zero. Let $\sigma(M)$ represent the sum of entries in matrix $M$. Let $B_+$ and $B_-$ be the submatrix of $B$ corresponding to $C_{+}$ and $C_{-}$, respectively.

Then we conclude that $\sigma(B_+) = \sigma(B_-)$. Let $c_j$ be the $j$-th column vector of $B$, and $\sigma(c_j)$ its sum, which is even by hypothesis. We can write $\sigma(B_+)$ as: $$\sigma(B_+) = \sum_{j \in C_{+}} \sigma(c_j)$$ Which tells us that $\sigma(B_+)$ is even, say $2k$. Finally, we have that $\sigma(B) = \sigma(B_+) + \sigma(B_-) = 2 \sigma(B_+) = 4k$. QED. Note: nowhere in the proof do we seem to require that $B$ be square.