kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > The Residue Theorem

The Residue Theorem

16 Apr 2025

“Why does a mathematician call their dog Cauchy?” (answer in the Conclusion)

This is a post with my notes on complex integration, corresponding to Chapter 4 in Ahlfors’ Complex Analysis.

In the last post of the series, we studied The General Form of Cauchy’s Theorem . One of the outcomes in generalizing it for multiply connected regions was the concept of the modules of periodicity. In this post we’ll explore this idea further and see how it can be used as a tool for solving integrals, via Cauchy’s Residue Theorem.

Residues

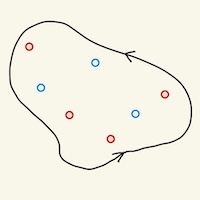

Supose a function $f(z)$ that is holomorphic in a (simply connected) region $\Omega$ except at a finite number of singularities $a_1, \cdots, a_n$. We can obtain a multiply connected region $\Omega’$ by removing these points, so that $f(z)$ becomes holomorphic in $\Omega’$.

We can choose our “canonical” closed curve (see Multiply Connected Region in [2]) for each of the holes in $\Omega’$ as a circle $C_j$ centered in $a_j$, sufficiently small that it’s contained in $\Omega’$.

So the corresponding module of periodicity is

\[P_j = \int_{C_j} f(z)dz\]Now suppose we plug the function $1/(z - a_j)$. Then we have

\[P_j = \int_{C_j} \frac{1}{z - a_j} dz\]From our winding number post [3] we have that:

\[n(\gamma, a_j) 2\pi i = \int_{C_j} \frac{1}{z - a_j} dz\]Since $C_j$ winds around $a_j$ exactly once, so $n(\gamma, a_j) = 1$, we conclude that the period for $1/(z - a_j)$ is exactly $2\pi i$.

Because it’s an integral, the period of a function is also a linear function. So the period of $f(z) - \alpha / (z - a_j)$ is the period of $f(z)$ minus $\alpha$ times the period of $1/(z - a_j)$. We want to choose $\alpha_j$ so that the period of $f(z) - \alpha_j / (z - a_j)$ is 0. We can do:

\[\int_{C_j} f(z) - \alpha_j g(z) dz = P_j - \alpha_j 2\pi i = 0\]So that

\[\alpha_j = \frac{P_j}{2 \pi i}\]The scalar $\alpha_j$ is defined as the residue. So the function $g(z) = f(z) - \alpha_j / (z - a_j)$ is such that:

\[\int_{C_j} g(z) = 0\]By Corollary 1 in [4] we conclude that $g(z)$ is the derivative of a holomorphic function in $\Omega’$. To avoid accounting for the other holes of $\Omega’$, we can shrink the domain to the annulus $0 \lt \abs{z - a_j} \lt \delta$. This let’s us defined the residue in simpler terms:

Definition. Let $f(z)$ be a holomorphic function except at an singularity $a$. The residue of $f(z)$ at $a$ is the scalar $R$ for which the function $f(z) - R / (z - a)$ is the derivative of a holomorphic function in $0 \lt \abs{z - a_j} \lt \delta$.

The residue can be denoted by $\mbox{Res}_{z = a} f(z)$. By this definition, $f(z) - R / (z - a)$ is not necessarily holomorphic in $0 \lt \abs{z - a_j} \lt \delta$, but by Corollary 1 in [4] we can claim that:

\[(1) \quad \int_{\gamma} \left( f(z) - \frac{\mbox{Res}_{z = a} f(z)}{z - a} \right) dz = 0\]We’ll come back to this equation later.

The Residue Theorem

In [2] we learned that the integral of a holomorphic function in a multiply connected region can be expressed as a linear combination of the modules of periodicity:

\[(2) \quad \int_\gamma f(z) dz = \sum_{j = 1}^{n - 1} c_j P_j\]where $c_j$ is the number of times $\gamma$ winds around the hole, or equivalently, the singularity $a_j$, or in short, $n(\gamma, a_j)$. Replacing these in $(2)$:

\[= \sum_{j = 1}^{n - 1} n(\gamma, a_j) P_j\]And using the residue definition:

\[\frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_\gamma f(z) dz = \sum_{j = 1}^{n - 1} n(\gamma, a_j) \mbox{Res}_{z = a_j} f(z)\]This is known as Cauchy’s Residue Theorem. Summarizing:

Theorem 1. Let $f(z)$ be a holomorphic function except for isolated singularities $a_j$ in a region $\Omega$. Then:

\[(3) \quad \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_\gamma f(z) dz = \sum_{j = 1}^{n} n(\gamma, a_j) \mbox{Res}_{z = a_j} f(z)\]For any cycle $\gamma$ that is homologous to 0 in $\Omega$ not passing through any of the singularities.

Application: Poles

One question we might ask ourselves is why are residues useful? Couldn’t we just use the definition of modules of periodicity directly? Why do we need residues which is just modules of periodicity divided by $2 \pi i$?

The advantage is not on the definition of the residue itself but rather because of equation $(1)$:

\[\int_{\gamma} \left( f(z) - \frac{\mbox{Res}_{z = a} f(z)}{z - a} \right) dz = 0\]Suppose we can write $f(z)$ as:

\[f(z) = \frac{\alpha}{z - a} + g(z)\]where $g(z)$ is the derivative of a holomorphic function. Then $\alpha$ is the residue! This is particularly useful if the singularity is a pole. In Lemma 4 in [5], we showed that if $f(z)$ has a pole of order $m$, it can be written as the Laurent series:

\[f(z) = \sum_{n=-m}^{\infty} c_n (z - a)^n\]Where $c_{-m} \ne 0$. For the analytic part of the series (i.e. those containing terms with non-negative values of $n$) we have the standard Taylor series, so we know by [6] that it forms a holomorphic function. We can write it as:

\[f(z) = g(z) + \sum_{n=1}^{m} c_{-n} (z - a)^{-n}\]Isolating the term $n = 1$:

\[f(z) = g(z) + \frac{c_{-1}}{z - a} + \sum_{n=2}^{m} c_{-n} (z - a)^{-n}\]We claim that $f(z) - c_{-1} / (z - a)$ is the derivative of a holomorphic function. To do so, we can analyze each term on the right hand side in turn: $g(z)$ is holomorphic, so by [4] it has a holomorphic anti-derivative. For $n \ge 2$, the term $c_{-n} (z - a)^{-n}$ is the derivative of $c_{-n} (z - a)^{-n + 1} / (-n + 1)$. Thus the definition of residue applies and we conclude that $c_{-1}$ is exactly the scalar we’re looking for.

Examples

Example 1. Compute the residues of

\[\frac{\alpha}{z - a} + \frac{\beta}{z - b}\]It has poles $a$ and $b$. The residue for $z = a$ is $\alpha$ because $\beta/(z - b)$ is holomorphic in the annulus $0 \lt \abs{z - a} \lt \delta$. By analogous reasoning $\beta$ is the residue for $z = b$.

Example 2. Compute the residues of

\[\frac{e^{z}}{(z - a)(z - b)}\]For $a \ne b$. We can compute the Laurent series expansion around $a$ to conclude the residue for that pole is $e^a / (a - b)$ (Lemma 4) and similarly for $b$ that the residue is $e^b / (b - a)$.

Connections

We can obtain Cauchy’s Integral formula from $(3)$, by using the function $f(z) / (z - a)$, where $f(z)$ is holomorphic in $\Omega$. Since $f(z)$ is holomorphic, it’s analytic [6] and can be written as the convergent series:

\[(4) \quad f(z) = \sum_{j = 0}^{\infty} c_j (z - a)^j\]Dividing by $(z - a)$ and isolating the first term we get:

\[\frac{f(z)}{z - a} = \frac{c_0}{z - a} + \sum_{j = 1}^{\infty} c_j (z - a)^{j - 1}\]The summand on the right hand side forms a series corresponding to a holomorphic function, and as we’ve seen in the Application: Poles section, that means that $c_0$ is the residue of $f(z) / (z - a)$. The coefficient $c_0$ can be found via $(4)$ be setting $z = a$, which gives us $f(a)$, thus we can replace those in $(3)$ to obtain:

\[\frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_\gamma f(z) dz = n(\gamma, a) f(a)\]If we assume $n(\gamma, a) = 1$ we obtain exactly Cauchy’s Integral Formula (Lemma 1 in [7]).

The Argument Principle

In The Open Mapping Theorem [8] we proved the following Lemma (Lemma 10 in the Appendix):

Let $f(z)$ be a holomorphic function in $\Omega$ and $z_1, z_2, \cdots, z_n$ be its zeros, and $m_1, m_2, \cdots, m_n$ their order. Let $\gamma$ be a closed curve in $\Omega$ and $n(\gamma, a)$ the winding number of a point $a$.

Then:

\[\sum_{i = 1}^n n(\gamma, z_i) m_i = \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{f'(z)}{f(z)}dz\]

We can prove it using the residue theorem. If $f(z)$ has zeros $z_1, z_2, \cdots, z_n$ of respective order $m_1, m_2, \cdots, m_n$, then from Lemma 1 in [8], we can write it as:

\[f(z) = (z - z_1)^{m_1}(z - z_2)^{m_2} \cdots (z - z_n)^{m_n} g(z) = g(z) \prod_{j = 1}^{n} (z - z_j)^{m_j}\]where $g(z)$ is a holomorphic function with $g(a) \ne 0$. Differentiating it gives us the equation:

\[f'(z) = g'(z) \prod_{j = 1}^{n} (z - z_j)^{m_j} + \\ g(z) \sum_{j = 1}^{n} m_j (z - z_j)^{m_j - 1} \prod_{k = 1, k \ne j}^{n} (z - z_k)^{m_k}\]We can replace the definition of $f(z) / g(z) = \prod_{j = 1}^{n} (z - z_j)^{m_j}$ back here and get:

\[f'(z) = g'(z) \frac{f(z)}{g(z)} + \\ g(z) \sum_{j = 1}^{n} m_j (z - z_j)^{m_j - 1} \frac{f(z)}{g(z) (z - z_j)^{m_j}}\]Cancelling terms:

\[f'(z) = g'(z) \frac{f(z)}{g(z)} + \sum_{j = 1}^{n} m_j \frac{f(z)}{(z - z_j)}\]Dividing by $f(z)$:

\[\frac{f'(z)}{f(z)} = \frac{g'(z)}{g(z)} + \sum_{j = 1}^{n} \frac{m_j}{(z - z_j)}\]The first term is a holomorphic function because $g(z) \ne 0$. The other terms have poles at $z_j$. As we saw in Example 1, the residue for pole $z_j$ is $m_j$. Plugging these into $(3)$ gives us, for the function $f’(z) / f(z)$:

\[(5) \quad \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_\gamma \frac{f'(z)}{f(z)} dz = \sum_{j = 1}^{n} n(\gamma, a_j) m_j\]Note that nowhere in our calculation we require $m_j$ to be positive. We can thus generalize Lemma 1 in [8] with Lemma 2:

Lemma 2. Let $f(z)$ be a function with zeroes $z_1, z_2, \cdots, z_{n_z}$ of order $m_1, m_2, \cdots, m_{n_p}$ and poles $p_1, p_2, \cdots, p_{n_p}$ of order $n_1, n_2, \cdots, n_{n_p}$. Then $f(z)$ can be written as:

\[f(z) = \frac{\prod_{j}^{n_z} (z - z_j)^{m_j}}{\prod_{j}^{n_p} (z - p_j)^{n_j}} g(z)\]Where $g(z)$ is a non-zero holomorphic function.

Which we can simplify as a single product where some of the exponents might be negative. This allow us to generalize $(5)$ to Theorem 3, known as the Argument Principle:

Theorem 3. Let $f(z)$ be a function with zeroes $z_1, z_2, \cdots, z_{n_z}$ of order $m_1, m_2, \cdots, m_{n_p}$ and poles $p_1, p_2, \cdots, p_{n_p}$ of order $n_1, n_2, \cdots, n_{n_p}$:

\[(6) \quad \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_\gamma \frac{f'(z)}{f(z)} dz = \sum_{j = 1}^{n} n(\gamma, z_j) m_j - \sum_{j = 1}^{n} n(\gamma, p_j) n_j\]For any cycle $\gamma$ homologous to 0 in $\Omega$ that does not pass through any of the zeros or poles.

Why is it called the argument principle? We have that $f(z)$ is a complex number so we can write it as:

\[f(z) = \abs{f(z)}e^{i \mbox{arg}f(z)}\]Taking the logarithm:

\[\ln f(z) = \ln \abs{f(z)} + i \mbox{arg} f(z)\]Differentiating

\[\frac{d \ln f(z)}{dz} = \frac{d}{dz} \ln \abs{f(z)} + i \frac{d}{dz} \mbox{arg} f(z)\]So the change in $f(z)$ for a small delta $dz$ corresponds to a change in magnitude ($\abs{f(z)}$) and in argument ($\mbox{arg} f(z)$). We also have the identity:

\[\frac{d \ln f(z)}{dz} = \frac{f'(z)}{f(z)}\]So when we integrate the right hand size over $\gamma$, we’re computing the overall change in magnitude and argument. However, $(6)$ only has the imaginary part (multiply both sides by $i$ to see it). This means the net change in magnitude of $f(z)$ is 0. The net change in argument, let’s call it $\Delta_{\mbox{arg}}$ can be obtained via:

\[\int_\gamma \frac{f'(z)}{f(z)} dz = i \Delta_{\mbox{arg}}\]Or that,

\[\Delta_{\mbox{arg}} = 2 \pi \left(\sum_{j = 1}^{n_j} n(\gamma, z_j) m_j - \sum_{j = 1}^{n_p} n(\gamma, p_j) n_j\right)\]If $\gamma$ is a simple curve and we only count zeros and poles contained inside the curve, we get:

\[\Delta_{\mbox{arg}} = 2 \pi \left(\sum_{j = 1}^{n_j} m_j - \sum_{j = 1}^{n_p} n_j\right)\]Note that $m_j$ and $n_j$ are integers so $\Delta_{\mbox{arg}} = 2\pi k$, with $k$ corresponding to how many revolutions $f(z)$ performed around the origin as $z$ went around $\gamma$. It makes intuitive sense since $z$ is travelling around a closed circle, so it starts and stop at the same place.

Conclusion

The answer to the question at the start is: “Because it leaves residues on every pole!”

Coincidentally, I just heard this joke recently on the Oxford Mathematics Instagram account as I was finishing up this post! I would have not gotten the joke before studying this topic.

In this post we saw that residues are connected to modules of periodicity but they’re easier to compute, and like modules of periodicity they’re useful because the integral of a function can be expressed as a linear combination of them. Residues are particularly easy to find at poles.

We learned about some connections between residues and Cauchy’s Integral Formula and also that the change in argument of a function over a curve can be computed from the difference of zeros and poles of a function contained inside it.

Appendix

Lemma 4. In the Laurent series expansion of $e^z / ((z - a)(z - b))$ around the pole $a$, the coefficient $c_{-1}$ is $e^a / (a - b)$.

References

- [1] Complex Analysis - Lars V. Ahlfors

- [2] NP-Incompleteness: The General Form of Cauchy’s Theorem

- [3] NP-Incompleteness: The Winding Number

- [4] NP-Incompleteness: Cauchy Integral Theorem

- [5] NP-Incompleteness: Zeros and Poles

- [6] NP-Incompleteness: Holomorphic Functions are Analytic

- [7] NP-Incompleteness: Cauchy’s Integral Formula

- [8] NP-Incompleteness: The Open Mapping Theorem