kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > The Jemalloc Memory Allocator

The Jemalloc Memory Allocator

15 Jul 2025

A memory allocator is an algorithm that implements calls such as malloc() and free(), which allocate and deallocate memory, respectively.

The standard specifies some constraints on the how these functions behave but not how they’re implemented. Hence, custom implementations are often used. In this post we would like to discuss one of them, known as jemalloc.

Note: the contents of post is based on the 2007 paper A Scalable Concurrent malloc(3) Implementation for FreeBSD [1] and the implementation is likely very different today, but I’m mostly interested in the high-level ideas.

Motivation

Over the years different implementations for malloc were created, either to address problems in the standard one or to make it work better for specific use cases. I’m not sure when the trend started, but it seems customary to name the specific malloc implementation after the author. For example phkmalloc is named after Poul-Henning Kamp. Similarly, jemalloc is named after Jason Evans.

Many old memory allocators were implemented before multi-core hardware were popular and don’t take advantage of them. This was the motivation for the creation jemalloc.

Custom Allocators

When we compile a C/C++ program, it uses a default implementation for malloc() and free(), but it can be customized by linking the appropriate library during compilation.

For example, we can use jemalloc’s implementation by linking with the ljemalloc library, which then overrides the functions malloc() and free(), taking precedence over the default ones.

Notice this a user space implementation, so it’s completely transparent to the operating system. Internally the allocators use lower-level system calls such as mmap() or brk().

We’re now going to cover some aspects of jemalloc.

Multi-threads and Arenas

When multiple threads are allocating and deallocating memory, it can lead to contention because the memory allocators need to lock memory regions to be able to perform its operations.

The idea then is to partition the memory into arenas, and have each thread assigned to one arena, so that threads from different arenas don’t compete for the same region of memory. The allocator still needs to make sure the process in thread safe, but with fewer threads competing for the same resource contention is reduced.

Arena is only used for allocations. This means that a thread can only allocate memory in its own arena but it can read and deallocate memory from different arenas. Isn’t there contention for deallocation then? Perhaps the assumption is that in most cases the thread that deallocates memory is the same one that performed allocation, so the arena principle should help.

The allocator assigns an arena to a thread the first time it allocates or deallocates memory, in a round-robin fashion. To store the association between thread and arena, it leverages Thread-Local Storage or TLS (in which each thread has a dedicated region in memory).

The number of arenas is suggested to be 2-4 time the number of CPU cores. We may wonder why it doesn’t simply create one arena per thread? This could lead to inefficient use of memory because if only a few threads ever allocate memory the arenas from the remaining threads would go unutilized.

Internal vs. External Memory Fragmentation

When our program requests X amount of memory, the allocator will typically allocate more memory than that (typically the next power of 2). For example, if we ask for 13 bytes of memory, the allocator might give us 16 bytes, 3 bytes of which are wasted. This is known as internal memory fragmentation.

You might then ask why not have the allocator return exactly the same amount we ask for and have 0 internal fragmentation. It becomes a problem when it frees that memory later and tries to reuse it. Suppose we have a region of memory of size 16 bytes. We send requests R1 of 3 bytes and R2 of 6 bytes to the allocator, that then allocates them contiguously as show in Figure 1:

Now suppose we deallocate R1, freeing 3 bytes and send a new request R3 of size 8 bytes. This request cannot be fulfilled as shown in Fig 2. The space left because we can’t allocate more blocks is called external memory fragmentation. This is hard to quantify precisely because the amount of fragmentation depends on the size of the request. For example, if R3 was of size 7 bytes or less, we’d be able to fulfill it. But in general it represents wasted space outside the block.

If all blocks had the same size, there would be no external fragmentation. If we set it to 8 bytes in our example, it would have been able to fulfill R3.

On the other hand, in practice a fixed-sized block would have to be a big enough to support all sorts of requests, so in most cases it would lead to a lot of internal fragmentation if there are a lot of small allocations.

A middle ground solution would be to have a fixed-sized block with capacity to fulfill most requests, but for large requests we attempt to find multiple contiguous blocks.

As we can see, there’s a tradeoff between internal and external fragmentation and allocation algorithms such as the Buddy Memory Allocation discussed below tries to find a good balance.

Buddy Memory Allocation

This is an algorithm jemalloc uses to fit small segments of memory into a larger one. We discussed this algorithm in detail in the post Buddy Memory Allocation.

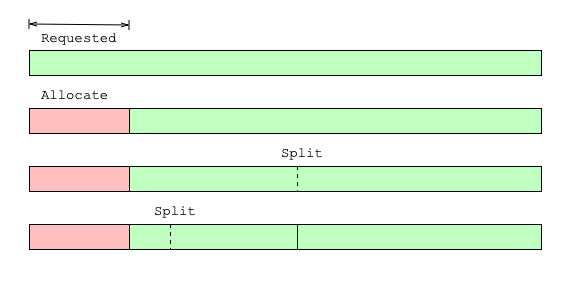

To summarize: the general idea of the buddy algorithm is that it starts with one contiguous segment of memory. When a request for X bytes comes it, it tries to find the smallest block larger than X. If the block is more than twice the size of X, it first splits the block into two and repeats the process with the first of the two blocks. Fig 3 from [3] shows it in action.

In the jemalloc paper [1], the author calls the buddy algorithm block a page run. The reason being that the smallest size a block can be subdivided into is the size of a page (4kB), so blocks represent sets of contiguous (runs) pages.

Data Structures

Chunks

Each arena divides its portion of memory into equally sized blocks called chunks, which typically are 2MB in size.

Allocation Classes

When we request X bytes, this request is categorized into one of the 3 classes based on X:

- Small: up to 2kB (1/2 the size of a page)

- Large: up to 1MB (1/2 the size of a chunk)

- Huge: rest

The small class is subdivided into subclasses:

- Tiny: up to 8B

- Quantum-spaced: up to 512B

- Sub-page: up to 2kB

Note that when we say a class supports up to X bytes, it doesn’t mean it uses a block of that size. For example, suppose we request 200 bytes of memory. The size of the block we need is found by rounding it to the next power of 2, which is 256 bytes. This request falls into the Quantum-spaced class, but the amount requested will be 256 bytes, not 512 bytes.

The motivation for having higher granularity (in terms of block sizes) for the small allocations is that most allocations are small, so it’s worth reducing internal fragmentation for those, even though it might cause more external fragmentation.

In many systems, the spec dictates that malloc() is required to allocate memory segments aligned at 16 bytes, meaning that the smallest block size is 16 bytes and in this case the tiny class is not used.

Huge Allocations. For huge allocations, jemalloc assigns them to one or more contiguous chunks, effectively operating as a fixed-size block allocator discussed in Internal vs. External Memory Fragmentation. However in this case, the internal fragmentation would be bounded to 1/2 of a chunk size.

Metadata for huge allocations is stored in a single black-and-red tree, shared by all arenas. The rationale is that huge allocations are rare and contention is not an issue.

Large Allocations. Each chunk is managed by a buddy allocation instance. A large allocation is directly managed by the algorithm. That is, it finds a suitable page run that can fit the request and that page run is used as the memory segment.

Small Allocations. Because a page run is at least a page in size (4kB), allocating small requests to a single page run would be wasteful. Instead there’s another layer of allocation happening within a page run, that is, multiple small segments can be assigned to the same page run.

However, each small subclass of the small size is handled by different runs, i.e. we cannot mix different small subclasses within the same page run.

At any given time only one run for each small class is active. It stays active until it cannot allocate any more requests. In order to choose the next run to use, we store the percentage full of each run. The algorithm es for the new run in this order of fullness: P50, P25, P0 and then P75. The rationale for leaving P75 to last is that constantly choosing almost full runs would cause the active run to change often.

Noting that we can deallocate from an arbitrary run (wherever the segment was located) but this doesn’t cause the active run to change, just that the percentage full drops.

I was wondering why we don’t just reduce the minimum size of a page run in the buddy algorithm so that it can support the smaller allocations and not have to handle small allocations differently from large ones.

The reason seems to be that we need store metadata about each page run and having small page runs could lead to too many of them, leading to too much space used for metadata. By batching small allocations into one run and using a greedy algorithm for allocation, the metadata needed is smaller. So we’re trading off a more efficient algorithm for a reduced metadata overhead.

Conclusion

I started reading this paper in 2020 (5 years ago), but soon ran into concepts I didn’t know enough to understand the paper well. This led me to write about CPU cache and the Buddy Memory Allocation algorithm, but after that I completely abandoned the effort.

That was when I was still doing frontend work, so I was reading it out of curiosity. Now I do backend work and memory allocation plays a more direct role in my work and thus studying this topic became more important.

By some huge coincidence, Evans recently wrote a postmortem about jemalloc less than a month ago [2]! That post provides an interesting history of jemalloc and its relationship with Facebook/Meta. The sad thing I learned from his post is that jemalloc doesn’t have a future as an open source project.

Relate Posts

T-digest in Python. While solving a different problem with a different solution, jemalloc reminds me of the T-digest algorithm. In particular, that it has to deal with different granularities for different distributions.