kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Buddy Memory Allocation

Buddy Memory Allocation

31 Jul 2020

In this post we’ll discuss an algorithm for dynamic memory allocation known as the Buddy Algorithm. It’s performs well in practice in terms of reducing internal memory fragmentation and is used by popular memory allocators.

We’ll first present the problem we’re trying to solve, then describe the Buddy algorithm and a Python implementation at a high-level, for didactic purposes. Finally we’ll do some simple time-complexity analysis.

Problem

Assume we have a memory of size \(2^m\) (bits). We want to develop an allocator that can receive requests asking for an amount of size k of (contiguous) memory. The allocator either declares no memory is available, or it allocates a block of size k and returns its address. It can also receive requests to free previously allocated memory given the block address.

Algorithm

From now on, for didactic purposes, we’ll assume our memory is represented by a big array and the adress correspond to the array indices.

Our data structure is comprised of blocks representing chunks of available memory. Their sizes are always some power of 2. We start with a single block of size \(2^m\), representing the whole array.

When a request asking for a block of size k comes, it looks for the smallest available block whose size is equal or larger than k.

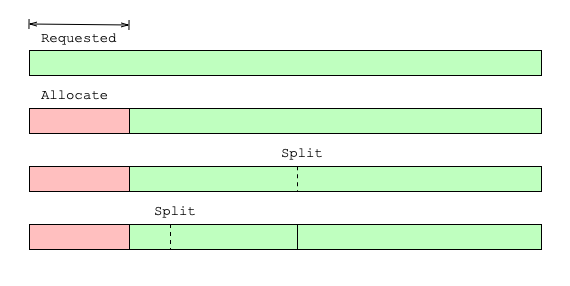

If k is less than half the size of the block, it is split into two (left, right), and the two resulting blocks are called buddies. If k is still less than half the size of left buddy, the split process continues until k is larger than half of the resulting buddy. See Figure 1 for an example.

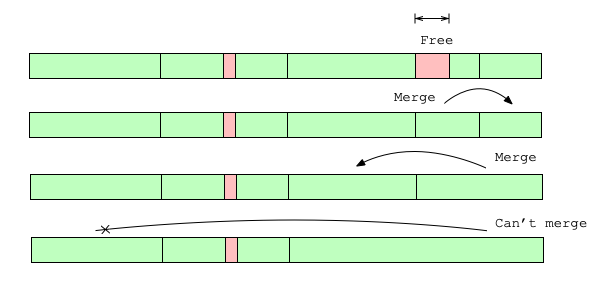

When a block is released, we will try to merge it with its buddy. There are 3 conditions in which this won’t be possible:

- The released block has size \(2^m\) so it’s the entire memory and has no buddy

- The buddy block is still being used

- The buddy block is partially used (some portion of it is allocated) - this is indicated by the buddy having a size smaller than the released block (See last step of Figure 2 for an example).

If a buddy is found we combine them into one block. We repeat this process while there’s an available buddy to merge.

Note from Figure 2 that the buddy of a block can be either before or after it in memory.

Implementation details

Block Structure

Each block will have metadata to store whether it’s available and its size class (the exponent of the power of 2). We store it inline with the block, by reserving the first few indexes to it. We have to store it inline because we don’t have access to dynamic memory to store it elsewhere. Remember we need this algorithm to allocate dynamic memory!

To quickly find the first available block of a given size, we keep m doubly-linked lists. The reason for the double-link is that we can quickly remove a block from the list just from its address.

Thus, the memory layout of a block is:

| Available? | Size Class | Previous Block’s Address | Next Block’s Address | Actual Memory |

The k-doubly linked list contains all the available blocks of size k. We use a sentinel node to avoid having to handle corner cases when the list is empty.

Finding the Buddy

We can show (see Appendix) that a block of size \(2^k\) has an address that is a multiple of \(2^k\), so \(C2^k\) for some constant \(C\). When splitting such a block into two, we’ll have addresses \(C 2^k\) and \(C 2^k + 2^{k-1}\), so the buddy address of \(C 2^k\) is \(C 2^k + 2^{k-1}\) and vice-versa.

More generally we can find the address \(B\) of the buddy of a given address \(P\) and size class \(k\) via:

If \(P \mod 2^{k + 1} = 0\) then \(B = P + 2^k\) else \(B = P - 2^k\).

Another way to see this is that a block of size k and its buddy have address \(C 2^{k+1}\) and \(C 2^{k+1} + 2^{k}\) (not necessarily in this order). \(C 2^{k+1}\) in binary will have at \(k+1\) trailing zeros, and if we add \(2^{k}\) to it, since the k-th bit is 0, \(C 2^{k+1} + 2^{k}\) has the k-th bit equals to 1, and that’s the only bit they differ on. Hence we can obtain the buddy address of a given block of size \(2^k\) by simply flipping the \(k\)-th bit! This is suggested by Knuth in [2].

We can use bitwise operators in Python to accomplish that, as shown in the implementation of buddy_address().

Allocating

First we find the smallest block that is larger than the requested size \(S\). We can simply iterate over the heads of the linked lists and find the first non-empty one that is larger than \(S\).

Let \(P\) be the address of such block and its size class \(k\). First we remove \(P\) from its doubly-linked list.

Then we split the block at index \(P\):

- Find the address \(B\) of the buddy, as described above.

- Set the size class of \(B\) to \(k-1\), mark it as free.

- Set \(k = k - 1\)

- Repeat while \(2^{k-1} \ge 2S\)

After all the splitting we mark \(P\) as used.

Freeing

To free a block with address \(P\) of size \(k\), we first mark it as available. Then we find the address \(B\) of the buddy, as described above.

Check if we can merge:

- Block at \(B\) is available

- Size of block at \(B\) is \(k\) (same as the one at \(P\))

- Size of block at \(P\) is less than \(m\)

If so, we merge:

- Remove \(B\) from the list of size \(k\)

- Set \(k = k + 1\)

- Set \(P = \min(P, B)\) (so it points to the first of the two).

- Repeat while merging is possible

Once the merge is finished we set \(P\)’s size class to \(k\). Finally we insert the block into the list of size \(k\).

Python Implementation

Memory

We first define a class to represent the memory.

class Memory:

def __init__(self, size):

self.memory = bitarray([0]*size, endian='little')We use a bit-array to make efficient use of space, but we should be able to implement in other ways, for example a regular Python list, a binary file in disk, etc.

The key is to provide an interface such that these details don’t matter. We need methods to write and read from memory, but we also need to know the sizes of the values so they can be properly stored and retrieved.

We could either pass the size as argument, but we opted to have a method for each type for readability, for example, booleans and 32-bit integers:

def set_bool(self, addr, val):

self.memory[addr] = val

def get_bool(self, addr):

return self.memory[addr]

def set_i32(self, addr, val):

bitarr = int2ba(val, length=INT_SIZE, endian='little')

self.set_bitarray(addr, bitarr)

def get_i32(self, addr):

bitarr = self.memory[addr:addr + INT_SIZE]

val = ba2int(bitarr)

return valBecause we’re working with bit-arrays, we need to convert integers to/from its binary representation before writing/reading from memory. We also need to be consistent with the endianess: in this case we use little endian, so that the lowest bit of the number is written first to memory.

Block

Next we model the block. The purpose of this class is to hide the internal layout of its representation in memory.

class Block:

def __init__(self, addr, memory):

self.memory = memory

self.addr = addrNote that Block doesn’t have its own state. It only holds references to memory and addr.

Internally we need to worry about offsets and handle the “pointer arithmetic” but to the outside we only expose high-level getters and setters, for example, the size:

# Layout: FLAG | SIZE | PREV | NEXT | ACTUAL_MEMORY

FLAG_SIZE = BOOL_SIZE

# ...

OFFSET_SIZE = FLAG_SIZE

class Block:

# ...

def set_size(self, size):

self.memory.set_i32(self.addr + OFFSET_SIZE, size)

def get_size(self):

return self.memory.get_i32(self.addr + OFFSET_SIZE)The block also represents a node in a linked list, so we can have convenience methods for inserting a block in front of it and removing itself from whichever list it’s at.

def insert_after(self, block):

next_block = self.get_next()

self.set_next(block)

block.set_prev(self)

next_block.set_prev(block)

block.set_next(next_block)

def remove_from_list(self):

next_block = self.get_next()

prev_block = self.get_prev()

prev_block.set_next(next_block)

next_block.set_prev(prev_block)List of Blocks

In a (doubly)-linked list it’s convenient to use a setinel node, so we don’t have to ever work with the corner case where there are no nodes. We can define a class to encapsulate the sentinel and to expose list-specific methods such as clear(), is_empty(), get_first(), etc.

class BlockList:

def __init__(self, addr, memory):

self.head = Block(addr, memory)

def clear(self):

self.head.set_next(self.head)

self.head.set_prev(self.head)

def is_empty(self):

return self.head.get_next().equal(self.head)

def get_first(self):

assert not self.is_empty(), "List must not be empty"

return self.head.get_next()

def inset_front(self, block):

self.head.insert_after(block)List of Blocks by Size

For the Buddy Algorithm it’s convenient to represent the list of blocks by size class.

class BlockListBySize:

def __init__(self, lower_bound_size, upper_bound_size, memory):

self.lower_bound_size = lower_bound_size

self.upper_bound_size = upper_bound_size

self.memory = memoryIt takes the lower and upper bound size classes and manages the BlockLists. The most interesting method in this wrapper is get_smallest_available_block() which finds the first size class that can hold the requested size:

def get_smallest_available_block(self, size):

for size_class in self.size_class_range():

block_list = self.get_block_list(size_class)

if (block_list.has_available_block(size)):

return block_list.get_first()

return NoneAllocating

Let’s first look at the allocation. It basically follows the steps listed in Implementation details.

def alloc(self, size):

free_blocks = self.get_free_blocks()

block = free_blocks.get_smallest_available_block(size)

if block is None:

raise Exception('Memory is full')

block.remove_from_list()

block = self.split(block, size)

block.set_used()

return block.get_user_addr()Note that in the last line we don’t return the block address directly but the user address hides the address space for the metadata the block keeps inline.

The split() finds the buddy address, set its metatada and add it to the list of free blocks:

def split(self, block, size):

free_blocks = self.get_free_blocks()

size_class = block.get_size_class()

# Keep splitting the blocks to avoid allocating too much memory

while size_class > MIN_SIZE_CLASS and \

Block.get_actual_size(size_class - 1) >= size:

new_size_class = size_class - 1

# Add the other half to the list

buddy = self.get_buddy(block, new_size_class)

buddy.set_free()

buddy.set_size_class(new_size_class)

free_blocks.add_block(buddy)

size_class = new_size_class

block.set_size_class(size_class)

return blockIt’s worth checking the get_buddy(). We need to discard the offset from the block addresses to make the math work:

def get_buddy(self, block, size_class):

virtual_addr = block.addr - self.block_memory_offset()

buddy_virtual_addr = buddy_address(virtual_addr, size_class)

buddy_addr = buddy_virtual_addr + self.block_memory_offset()

return Block(buddy_addr, self.memory)The buddy_address() function implements the formula we came up with above but we can use a neat bitwise trick. We basically want to flip the k-th (size_class) bit of the binary representation of the address, so we can do:

def buddy_address(addr, size_class):

return addr ^ (1 << size_class)Where ^ is a bitwise exclusive-or (XOR). For example, if class_size is 1, and the address is 100, the buddy address is 110, which is 100 ^ 10. Conversely, if the address is 110, the buddy address is 100, which is 110 ^ 10.

Freeing

Now let’s look at the free() method:

def free(self, user_addr):

block = Block.from_user_addr(user_addr, self.memory)

block.set_free()

self.merge(block)The interesting piece is the merge() function, which implements the step described in Implementation details. The core logic is determining when a buddy can be merged.

def merge(self, block):

free_blocks = self.get_free_blocks()

size_class = block.get_size_class()

while size_class < MAX_SIZE_CLASS:

buddy = self.get_buddy(block, size_class)

# Can't merge

if buddy.is_used():

break

# Buddy is not completely free (partially used)

if buddy.get_size_class() != size_class:

break

buddy.remove_from_list()

# Points to the leftmost of the pair (address of the merged block)

if (block.addr > buddy.addr):

block = buddy

size_class = size_class + 1

block.set_size_class(size_class)

free_blocks.add_block(block)The complete implementation is available on Github.

Time Complexity

All the blocks and list operations can be done in O(1). In the allocation method we might have to scan all the lists to find the smallest available block, so it’s O(m).

The splitting and merge are bounded by m, and each step is constant time. Overall then, both alloc() and free() has O(m) complexity, which is O(log n) for the size of the memory.

Conclusion

The same paper that prompted me to find out more about CPU caches made me want to understand how the Buddy Memory Allocation works.

The Wikipedia article is a good start and provides a good intuition, but lacks depth.

Fortunately Knuth wrote about it in The Art of Computer Programming but I had a lot of trouble following it. The content is dense and skips non-obvious steps. Moreover, it relied on concepts from previous sessions and used notation I’m unfamiliar with I had to do lookups often.

The idea of the algorithm is relatively straighforward but the implementation is hard mostly because the data structure is inline with the memory it’s allocating/freeing. That was a pretty interesting constraint.

I debated about whether to implement this is a low-level language like C or Rust and work with pointer arithmetic but opted to do in Python to the fully explicit about when working with addresses and to make it easier to understand by building on top of high-level abstractions.

I also started off by writing everything as a single function and wrote tests before refactoring. Particularly useful was encapsulating memory access into the Memory class, which made it very easy to swap the implementation using Python list with bit-arrays later.

Related Posts

- Skip Lists in Python and The Algorithm X and the Dancing Links are not really related but they also implement linked-structures in Python and hide their implementation details behind classes.

- CPU caches - we touched upon virtual memory in that post. We didn’t explicitly mentioned it here, but abstracting the offsets as we did in

block.get_user_addr()is in a way using virtual address which doesn’t directly map to the actual memory address.

References

- [1] Wikipedia - Buddy memory allocation

- [2] The Art of Computer Programming - Knuth, D. – Dynamic Storage Allocation (2.5)

Appendix

We claim that at any point in the Buddy Algorithm a block of size \(2^k\) has an address equals to \(C2^k\) for some integer constant \(C\).

We show by induction on \(k\). The base is \(k = m\), and the beginning of the initial block is 0, so the claim is trivially true.

Now if the claim is true any size class \(\ge k\), we show it’s true for \(k - 1\) as well. The only time we create new addresses is on split (on merge we just discard one of the addresses), so let’s consider that case. Say the block has size \(k\), so its address is \(P = C2^k\). We’ll split it into two blocks of size \(k - 1\), \(C 2^k\) and \(C 2^k + 2^{k-1}\). It’s easy to see both address are multiples of \(k - 1\), since \(C 2^k = (2C)2^{k-1}\) and \(C 2^k + 2^{k-1} = (2C + 1)2^{k-1}\), which proves our claim.