kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Symmetry Points of a Circle

Symmetry Points of a Circle

03 Feb 2024

In this post we study the Symmetry Points of a Circle in the context of Complex Analysis. It builds on concepts and results discussed in prior section, so it’s worth getting familiar with the series:

We can think of circle symmetry in analogy with conjugate points in the complex plane. For any given complex number $z$, with its conjugate $\overline{z}$ they form a pair of symmetric points with respect to the real line. Circle symmetry is similar, except the “line” of symmetry is the circumference of the circle.

Definition

Let $C$ be a circle and $T$ any Möbius transformation that maps the real line ($x$-axis in the Complex Plane) into $C$. Let $w = T(z)$ and $w^{*} = T(\overline{z})$. We then say $w$ and $w^{*}$ are symmetric with respect to $C$.

Lemma 1. For every circle $C$ there exists a Möbius transformation that maps the real line to it and vice-versa.

Let $C$ have center $z_0 = (x_0, y_0)$ and radius $r$. We'll first translate the circle so that its center lies at $z'_0 = (x'_0, y'_0) = (0, r)$, so if $\alpha = (-x_0, r - y_0)$, a translation $T(z) = z + \alpha$ will do. Now we use Lema 8 from [2], which claims that if $\abs{z'_0} = r$ (which is the case), then the inverse $U(z) = 1/z$ maps it to the line $2x'_0 x - 2y'_0 y = 1$. Since $x'_0 = 0$ and $y'_0 = r$, we have the line $y = -\frac{1}{2r}$. We follow with a translation by $\beta = (0, \frac{1}{2r})$, $V(z) = z + \beta$ which should give us $y = 0$.

Since Möbius transformations are composable, $VUT(z)$ is single Möbius transformation mapping the circle $C$ to the real line. We can put them together explicitly as: $$\frac{1}{z + \alpha} + \beta = \frac{\beta z + \beta \alpha}{z + \alpha}$$

The transformation mapping $w$ to $w^{*}$ is called a reflection. It can be obtained by applying $T^{-1}(w)$ to obtain $z$, then obtaining its conjugate $R(z) = \overline{z}$ and then applying $T(\overline{z})$ to obtain $w^{*}$, so $TRT^{-1}$. Note this is not a Möbius transformation because conjugation cannot be achieved via such transformations. Theorem 3 provides an explicit formula for the reflection.

To make the discussions and proofs easier, we’ll introduce the terms $w$-space and $z$-space. The $w$-space is the one containing the circle $C$ and the $z$-space is the image of the transformation $T$, i.e. the one where $C$ becomes the real-line.

Properties

We can characterize symmetric points by their cross ratio, as stated by Theorem 2.

Theorem 2 Let $C$ be a circle containing distinct points $w_1, w_2$ and $w_3$. Points $w$ and $w^{*}$ are symmetric with respect to $C$ if and only if $(w^{*}, w_1, w_2, w_3) = \overline{(w, w_1, w_2, w_3)}$.

Now we start with $(w^{*}, w_1, w_2, w_3) = \overline{(w, w_1, w_2, w_3)}$ and conclude from symmetric points $w$ and $w^{*}$ are symmetric. Let $T$ still be a Möbius transformation mapping points in $C$ to the real line. Again, using the fact that the cross ratio is invariant to Möbius transformations, we'll arrive at: $$(z^{*}, z_1, z_2, z_3) = \overline{(z, z_1, z_2, z_3)}$$ Replacing them in the definition of cross ratio: $$\frac{z^{*} - z_2}{z^{*} - z_3} \cdot \frac{z_1 - z_2}{z_1 - z_3} = \overline{\left(\frac{z - z_2}{z - z_3} \cdot \frac{z_1 - z_2}{z_1 - z_3}\right)}$$ And using conjugate identities: $$\frac{z^{*} - z_2}{z^{*} - z_3} \cdot \frac{z_1 - z_2}{z_1 - z_3} = \frac{\overline{z} - \overline{z_2}}{\overline{z} - \overline{z_3}} \cdot \frac{\overline{z_1} - \overline{z_2}}{\overline{z_1} - \overline{z_3}}$$ Recalling that $z_i$ is real (but $z$ not necessarily!), and thus equal to its conjugate: $$\frac{z^{*} - z_2}{z^{*} - z_3} \cdot \frac{z_1 - z_2}{z_1 - z_3} = \frac{\overline{z} - z_2}{\overline{z} - z_3} \cdot \frac{z_1 - z_2}{z_1 - z_3}$$ Cancelling terms leaves us with: $$\frac{z^{*} - z_2}{z^{*} - z_3} = \frac{\overline{z} - z_2}{\overline{z} - z_3} $$ or $$(z^{*} - z_2)(\overline{z} - z_3) = (\overline{z} - z_2)(z^{*} - z_3)$$ Distributing: $$z^{*}\overline{z} - \overline{z}z_2 - z^{*}z_3 + z_2z_3 = z^{*}\overline{z} - z^{*}z_2 - \overline{z}z_3 + z_2z_3$$ Cancelling terms and grouping by $\overline{z}$ and $z^{*}$: $$\overline{z}(z_3 - z_2) = z^{*}(z_3 - z_2)$$ Since $z_3 \ne z_2$, $z^{*} = \overline{z}$. Which means, by definition, $w$ and $w^{*}$ are symmetric points with respect to $C$.

In [1] Ahlfors actually uses Theorem 2 as a definition for symmetric points. We can use this theorem to come up with an explicit formula for obtaining $w^{*}$ from $w$ as stated in Theorem 3:

Theorem 3. Let $C$ be a circle with center $a$ and radius $R$, and points $w$ and $w^{*}$ symmetric with respect to $C$. Then

\[(1) \quad w^{*} = \frac{R^2}{\overline{w} - \overline{a}} + a\]We first start with a translation by $-a$: $$\overline{(w, w_1, w_2, w_3)} = \overline{(w - a, w_1 - a, w_2 - a, w_3 - a)}$$ We use Theorem 4 in [4] to obtain: $$= (\overline{w - a}, \overline{w_1 - a}, \overline{w_2 - a}, \overline{w_3 - a})$$ Geometrically speaking, we moved the circle $C$ to be centered at the origin, and $w_i - a$ are points in that circle. Thus we have that $(w_i - a)(\overline{w_i - a}) = \abs{w_i - a}^2 = R^2$ or that $\overline{w_i - a} = R^2 / (w_i - a)$. Replacing in the above: $$= \left(\overline{w} - \overline{a}, \frac{R^2}{w_1 - a}, \frac{R^2}{w_2 - a}, \frac{R^2}{w_3 - a}\right)$$ We follow with an inversion: $$= \left(\frac{1}{\overline{w} - \overline{a}}, \frac{w_1 - a}{R^2}, \frac{w_2 - a}{R^2}, \frac{w_3 - a}{R^2}\right)$$ And a homothety by $R^2$: $$= \left(\frac{R^2}{\overline{w} - \overline{a}}, w_1 - a, w_2 - a, w_3 - a\right)$$ And a translation by $a$: $$= \left(\frac{R^2}{\overline{w} - \overline{a}} + a, w_1, w_2, w_3\right)$$ Which conludes our proof.

Suppose that $C$ is the unit circle centered on the origin. Then $(1)$ becomes:

\[w^{*} = \frac{1}{\overline{w}}\]If we consider the polar form of these points $w = r_1 e^{i \theta_1}$ and $w^{*} = r_2 e^{i \theta_2}$, and noting that $\overline{w} = r_1 e^{-i \theta_1}$ and $1/\overline{w} = 1/r_1 e^{i \theta_1}$, we’ll obtain:

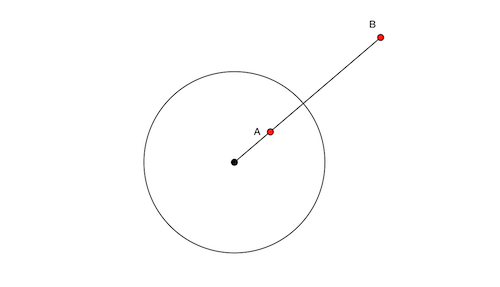

\[r_2 e^{i \theta_2} = \frac{R^2}{r_1} e^{i \theta_1}\]So we have $\theta_1 = \theta_2$, which implies that the points $w^*$ and $w$ have the same angle with respect to the origin and are thus collinear with it. Since lines are preserved under translation, they continue to be collinear for a circle centered in $a$.

Further $r_1 r_2 = R^2$, that is, the distance of the symmetric points $w$ and $w^{*}$ to the center of the circle are inversely proportional. Without loss of generality, assume that $r_1 \le r_2$. From these observations we derive many corollaries.

Let $C$ be a circle of radius $R$ and center $a$, and $w$ and $w^{*}$ symmetric points with respect to $C$. Then:

Corollary 4. The points $w$ and $w^{*}$ are collinear with point $a$.

Corollary 5. The distance $w$ and $w^{*}$ from $a$, $r_1$ and $r_2$ respectively, are inversely proportional, in particular:

\[(2) \quad r_1 = \frac{R^2}{r_2}\]If we set $r_1 = R$, we’ll obtain $r_2 = R$ and since they’re collinear by Corollary 4, they must coincide. In other words, $w$ is symmetric with itself, or that:

Corollary 6. If $w$ is in $C$, then $w = w^{*}$.

By setting $r_1 = 0$ in $(2)$, we’ll obtain $r_2 = \infty$, leading to:

Corollary 7. If $w = a$, then $w^{*} = \infty$

If $w \not \in C$, since we assume $r_1 \le r_2$ and have that $r_1 r_2 = R^{2}$, it must be that $r_1 \lt R$, and that $r_2 \gt R$, so we have that:

Corollary 8. If $w \not \in C$, then $w$ and $w^{*}$ lie on opposite sides of $C$.

Another characterization of the point symmetry is given by [5], stated here as Theorem 9:

Theorem 9. Let $C$ be a circle. Points $w$ and $w^{*}$ are symmetric with respect to $C$ if and only if every line and circle through $w$ and $w^{*}$ that intersects $C$, do so orthogonally.

We also know, from Theorem 3 in [2], that Möbius transformations are conformal maps, meaning that angles are preserved locally, that is, if two curves intersect at an angle $\theta$ in the domain space, when they get transformed, the corresponding curves also intersect at an angle $\theta$. Since $T$ is a Möbius transformation, a circle or line intersecting $C$ orthogonally in the $w-$space gets mapped to a circle or line intersecting the real line orthogonally in the $z-$space, and since $T^{-1}$ is also Möbius transformation, the converse also holds.

Now we assume one direction of the theorem, that $w$ and $w^{*}$ are symmetric with respect to $C$, so they get mapped, via $T$, to the conjugates $z$ and $\overline{z}$ in the $z$-space.

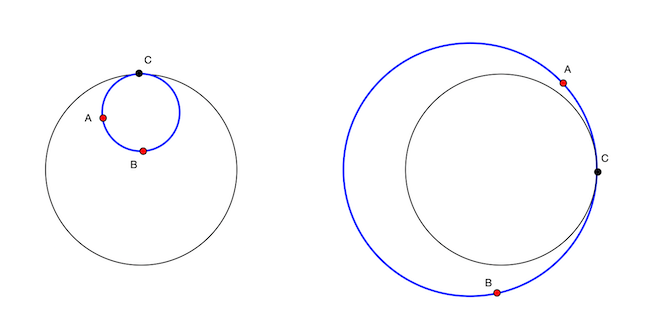

Corollary 8 shows that $w$, $w^{*}$ are on opposite sides of $C$, so either a line or a circle through them intersects $C$ at two points $p_1$ and $p_2$ in $C$ which get mapped to the real line as $T(p_1)$ and $T(p_2)$. Since $z$ and $\overline{z}$ are on different sides of the real line and $T(p_1) \neq T(p_2)$, the mapped curve must be a circle.

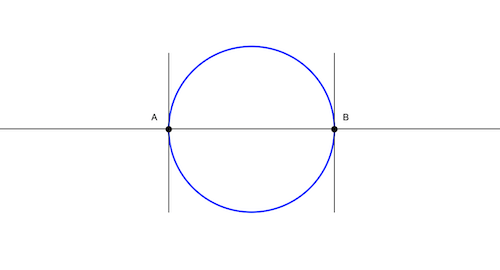

Since $z$ and $\overline{z}$ are symmetric with the real-line, it's possible to show that the points segment between $T(p_1)$ and $T(p_2)$ is a diameter of the circle $C'$, and that this circle intersects the real line perpendicularly. See Figure 9.1 for an intuition.

Now assume the other direction of the theorem, that we have 2 points $w$ and $w^{*}$ and that every circle or line through them that intersects $C$ does so orthogonaly. First we claim that $w$ and $w^{*}$ must be on opposite sides of $C$. If they're on the same side, there exists a cicle through them that is tangent to $C$ and hence doesn't intersect orthogonally. Figure 9.2 illustrates this.

The transformation $T$ will map the points $w$ and $w^{*}$ to points $z$ and $z^{*}$. We claim that $z$ and $z^{*}$ are on opposite sides of the real line. Otherwise there would exist a cicle through them that does not intersect the real line which would correspond to a circle or line through $w$ and $w^{*}$ in the $w$-space that does not intersect $C$, which would imply they're on the same side with respect to $C$, a contradiction.

Now that we know that $z$ and $z^{*}$ are on opposite sides of the real line, consider the line through them. It will intersect the real line at a point $p$. We claim that this line has to be perpendicular to the real line. Suppose it's not. Then the corresponding circle or line through $w$ and $w^{*}$ in the $w$-space will intersect $C$ (at the point $T^{-1}(p)$) in a non-perpendicular way (due to the conformal mapping property), which contradicts the hypothesis.

So we can assume $z$ and $z^{*}$ have the same $x$-value. It remains to show that $z$ and $z^{*}$ are equidistant from the real line and hence have opposite $y$-values. We notice that every circle through $z$ and $z^{*}$ will intersect the real line at two points $p_1$ and $p_2$, and it has to do so orthogonally. This means that $p_1p_2$ is a diameter of such circle and that the real line bisects it (see Figure 9.1). This means that points on this circle with the same $x$-value must have opposite $y$-values, so we conclude that $z$ and $z^{*}$ are conjugates. QED.

An important result is that point symmetry is preserved under Möbius transformations, as stated in Theorem 10.

Theorem 10. (Symmetry Principle) If a Möbius transformation maps a circle $C_1$ to $C_2$, then it maps any pair of symmetric points with respect to $C_1$ into a pair that is symmetric with respect to $C_2$.

Stereographic projection

One interesting way to see equation $(1)$ is it being a bijection from the interior of the circle to the exterior. In fact, this looks a lot like what the Stereographic projection does [6]: it maps points in the Northern hemisphere of the Riemann sphere to the exterior of the unit circle on the complex plane and points on the Southern hemisphere to the interior.

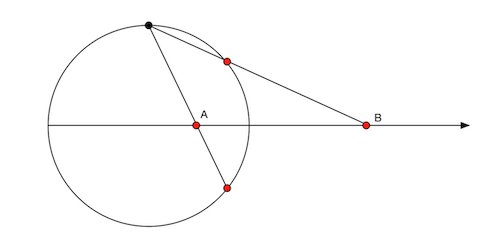

There’s actually a nice connection with Stereographic projection. If we take a point $p = (x_1, x_2, x_3)$ on the Riemann sphere and its symmetric point $p’ = (x_1, x_2, -x_3)$ with respect to the plane, then their corresponding projections will form a pair of symmetric points with respect to the unit circle in the extended complex plane.

To see why, we can use the equation for the projection onto the complex plane [6] to find the complex numbers for $p$ and $p’$, which we denote (conveniently!) by $w$ and $w^{*}$:

\[w = \frac{x_1 + ix_2}{1 - x_3}, \qquad w^{*} = \frac{x_1 + ix_2}{1 + x_3}\]Their modulus is given by:

\[\abs{w} = \frac{\sqrt{x_1^2 + x_2^2}}{1 - x_3}, \qquad \abs{w^{*}} = \frac{\sqrt{x_1^2 + x_2^2}}{1 + x_3}\]Multiplying them together, we get:

\[\abs{w}\abs{w^{*}} = \frac{x_1^2 + x_2^2}{1 - x_3^2}\]Since $p$ is on the sphere, $x_1^2 + x_2^2 + x_3^2 = 1$ or $x_1^2 + x_2^2 = 1 - x_3^2$. Thus $\abs{w}\abs{w^{*}} = 1$ and it’s possible to prove that they have the same argument and conclude that these pair of points are symmetric with respect to the unit circle in the extended complex plane.

Figure 2 illustrates this idea by analyzing a “cross-section” of the Riemann sphere and showing a projection of 2 points on the sphere that are symmetric with respect to the plane get mapped to points that are symmetric with respect to the unit circle.

Conclusion

The concept of symmetry with respect to a circle is intuitive if we take the conjugate symmetry as analogy. However, whereas the conjugate points $z$ and $\overline{z}$ are equidistant from the line of symmetry (i.e. the real-line), for the circle case, their distance that’s not the case. As a point in the interior of the circle moves away from the border, its corresponding symmetric point moves too, but much faster, as described by equation $(1)$.

The characterization from Theorem 9 [5], relating it to orthogonal intersections is a lot less intuitive.

As I was writing the post I started noticing some similarities with the Stereographic projections and the Riemann sphere, which I hadn’t seen during my research for the post. I was very happy to figure out a proof on my own and show that the correspondence is actually true.