kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Conformal Maps

Conformal Maps

30 Dec 2023

In this post we’ll discuss conformal maps, in particular understand its definition, provide examples and also make a connection with holomorphic functions.

This is part of the series on complex analysis. I recommend first checking the previous post:

Definition

A function $f: U \rightarrow V$ is called conformal (or angle-preserving) at a point $z \in V$ if it preserves angles between two directed curves through $z$ [4].

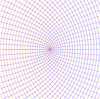

Let’s try to gain some intuition by considering an example in 2D. Let $\gamma_1$ and $\gamma_2$ be two arbitrary curves that pass through a point $z$. Consider the tangents of the curves at $z$. Since the curves are directed, we can use that to direct their tangents and find the angle between, which we’ll call $\theta$. Figure 1 (left) depicts an example.

We can apply a function $f$ to $\gamma_1$ and $\gamma_2$. Let’s denoted the resulting curves by $\xi_1$ and $\xi_2$ respectively. Since $z \in \gamma_1$ and $z \in \gamma_2$, we have that $w = f(z)$ belongs to $\xi_1$ and $\xi_2$. Now consider the tangents of $\xi_1$ and $\xi_2$ at $w$. If the angle between them is also $\theta$, then this function is conformal at $z$. Figure 1 (right) shows an example.

Parametric curves

A continuous curve in the complex plane can be thought as a function $\gamma(t): [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{C}$ where $t$ is from a real-number $a \le t \le b$. One intuitive way to see this is $\gamma$ being the path taken by a point from timestamp $a$ to $b$. This is called a parametric curve.

Tangent

Now that $\gamma$ is a function, it’s possible to calculate precisely the direction of the tangent at a given point $z_0 = \gamma(t_0)$, as we state in Lemma 1.

Lemma 1 Let $\gamma(t): [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{C}$ be a parametric curve. The direction of the tangent at point $z_0 = \gamma(t_0)$ is given by the argument of the complex number $z’$:

\[z' = \frac{d\gamma}{dt}(t_0)\]We need to choose $t_1$ as close as possible to $t_0$, so we account for any possible tiny local curvature around $t_0$, meaning that at that neighborhood the path from $\gamma(t_0)$ to $ \gamma(t_1)$ looks like a straight line. We can thus compute: $$\lim_{t_1 \rightarrow t_0} \frac{\gamma(t_1) - \gamma(t_0)}{t_1 - t_0}$$ which is the definition of $\frac{d\gamma}{dt}(t_0)$. As we see in the Figure above, this complex number represents a vector with the same direction as the tangent. We can compute the angle a complex number $z$ forms with positive x-axis via $\arg{(z)}$.

Curve Mapping

What happens when we apply a function $f$ over $\gamma$? We’ll obtain another curve $\xi$ which we can also see as a function of $t$ or as a composition of $f$ and $\gamma$:

\[\xi(t) = (f \circ \gamma)(t)\]Let $w_0 = f(z_0)$. What can we say about the tangent $w’$ of $\xi$ at $w_0$? Again suppose $z’$ is the tangent of $\gamma$ at $z_0$ and its angle with the origin is $\theta$, then Lemma 2 states that the angle of the tangent $w’$ with the origin is $\theta + \arg{(f’(z_0))}$.

Lemma 2 Let $\gamma(t): [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{C}$ be a parametric curve with tangent $z’$ at point $z_0$. Consider a function $f: \mathbb{C} \rightarrow \mathbb{C}$ which is holomorphic and with a non-zero derivative at $z_0$ and apply it over $\gamma$, obtaining the parametric curve $\xi(t) = (f \circ \gamma)(t)$.

Let $w_0 = f(z_0)$ and $w’$ be the tangent of $\xi$ at point $w_0$. The argument of $w’$ is given by

\[\arg{(w')} = \arg{(z')} + \arg{\left(\frac{df}{dz} (z_0) \right)}\]Holomorphic Functions

One way to interpret this Lemma 2 is that applying a function $f$ over a curve, cause its tangent at a point $z_0$ to rotate by the amount $\arg{(f’(z_0))}$, that only depends on the point $z_0$ but not on the curve itself.

This means that if two curves $\gamma_1$ and $\gamma_2$ intersect at $z_0$ at an angle $\theta$, applying the same function over them to obtain $\xi_1$ and $\xi_2$, both their tangents have been “rotated” by the same amount, so the angle between them is still the same.

This idea is formalized in Theorem 3.

Cauchy-Riemann Equations

As Theorem 4 states, it’s possible to show that conformal maps satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations [4], in which case we can use Theorem 1 from [4] to conclude that conformal maps are holomorphic functions.

The proof is quite long, so we'll first discuss the high level idea behind it. We'll basically show that $w'/z'$ is a complex number in the circumference of a circle, when we consider all possible curves $\gamma$ going through $z_0$. But because $f$ is conformal, we'll also show that $\arg{(w'/z')}$ is the same for all curves $\gamma$. The only way these two things can happen at the same time is if the circle has radius 0, because then all points in the circumference coincide and thus can have the same argument.

Now to the detailed proof. Since the image of $\gamma$ is a complex number, we can split it into two functions corresponding to the real and imaginary part, so $$(4.1) \quad \gamma(t) = x(t) + i y(t)$$ Where $x, y: [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. We can compute $z'$ via the derivative of $\gamma$ at $t_0$: $$z' = \frac{d\gamma}{dt}(t_0) = \frac{dx}{dt}(t_0) + i \frac{dy}{dt}(t_0)$$ We can also assume that $f$ now takes 2 variables $x, y$ instead of a complex number, $f(x, y)$, remembering that $x$ and $y$ are functions of $t$.

We can determine $w'$ by computing the derivative of $\xi = (f \circ \gamma)$ at a point $t_0$. For that we can use the chain rule of partial derivatives [5]: $$\frac{d\xi}{dt} = \frac{d(f \circ \gamma)}{dt} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \cdot \frac{dx}{dt} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \cdot \frac{dy}{dt}$$ Being super explicit with the function parameters (for clarity): $$\quad w' = \frac{d\xi}{dt}(t_0) = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x(t_0), y(t_0)) \cdot \frac{dx}{dt}(t_0) + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x(t_0), y(t_0)) \cdot \frac{dy}{dt}(t_0)$$ Recall that $z_0 = z(t_0) = x(t_0) + i y(t_0)$, so to simplify the notation, we'll denote the verbose $(x(t_0), y(t_0))$ by $(z_0)$, so: $$(4.2) \quad w' = \frac{d\xi}{dt}(t_0) = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(z_0) \cdot \frac{dx}{dt}(t_0) + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(z_0) \cdot \frac{dy}{dt}(t_0)$$ Notice that $\partial f / \partial x$ is independent of $\gamma$ when we consider it at a fixed point $z_0$. For example, if $f(x, y) = x^2 + i xy$, then $\partial f / \partial x = 2x + i y$. Evaluating at $z_0$ gives us $2 x_0 + i y_0$, so it only depends on $z_0$, not on $\gamma$. The same applies to $\partial f / \partial y$. Let's define: $$(4.3) \qquad z'_x = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(z_0), \qquad z'_y = \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(z_0)$$ We can replace these in $(4.2)$: $$(4.4) \quad w' = \frac{d\xi}{dt}(t_0) = z'_x \cdot \frac{dx}{dt}(t_0) + z'_y \cdot \frac{dy}{dt}(t_0)$$ Let's do some algebraic manipulation to find $dx/dt$ and $dy/dt$. First, consider the conjugate of $\gamma(t)$, $$\overline{\gamma(t)} = x(t) - i y(t)$$ If we differentiate with respect to $t$ and evaluate at $t_0$ we get: $$\frac{d\overline{\gamma}}{dt}(t_0) = \frac{dx}{dt}(t_0) - i \frac{dy}{dt}(t_0)$$ Which is the conjugate of $z'$, denoted by $\overline{z'}$. We can combine with $(4.1)$ and solve for $dx/dt (t_0)$ and $dy/dt (t_0)$: $$\frac{dx}{dt}(t_0) = \frac{z' + \overline{z}'}{2}, \qquad \frac{dy}{dt}(t_0) = \frac{z' - \overline{z'}}{2i}$$ Replacing in $(4.4)$: $$w' = z'_x \left(\frac{z' + \overline{z}'}{2}\right) + z'_y \cdot \left(\frac{z' - \overline{z'}}{2i}\right)$$ Multiplying the second term by $i/i$: $$w' = z'_x \left(\frac{z' + \overline{z}'}{2}\right) - i z'_y \cdot \left(\frac{z' - \overline{z'}}{2}\right)$$ We can re-arrange to isolate $z'$ and $\overline{z'}$: $$w' = \frac{(z'_x - i z'_y)}{2} z' + \frac{(z'_x + i z'_y)}{2} \overline{z'}$$ Dividing by $z'$: $$\frac{w'}{z'} = \frac{1}{2} (z'_x - i z'_y) + \frac{1}{2} (z'_x + i z'_y) \frac{\overline{z'}}{z'}$$ Since $z'_x$ and $z'_y$ are independent of $\gamma$, we can assume $(z'_x - i z'_y)/2$ and $(z'_x + i z'_y)/2$ are constant complex numbers $\alpha$ and $\beta$ and we get: $$(4.5) \quad \frac{w'}{z'} = \alpha + \beta \frac{\overline{z'}}{z'}$$ Now consider $z'$ in polar form, $z' = \abs{z'} e^{i\phi}$ and $\overline{z'} = \abs{\overline{z'}} e^{i \overline{\phi}}$. Since they're conjugate, they both have the same modulus: $$\abs{z} = \abs{\overline{z'}} = \sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}(t_0)\right)^2 - \left(\frac{dy}{dt}(t_0)\right)^2}$$ And opposite arguments: $$\phi = -\overline{\phi}$$ Thus $\overline{z'} / z' = e^{i(-2\phi)}$ and $$\beta \frac{\overline{z'}}{z'} = \abs{\beta} e^{\arg({\beta}) - 2\phi}$$ $(4.5)$ can be rewritten as: $$(4.6) \quad \frac{w'}{z'} = \alpha + \abs{\beta} e^{\arg({\beta}) - 2\phi}$$ Now we note that $z'$ is dependent of $\gamma$ because it represents its tangent at $z_0$. If we consider all possible curves that pass through $z_0$, we shall see all values of $\phi$ and thus $w'/z'$ will form a circle centered at $\alpha$ with radius $\beta$. Now let's compute the argument of $w'/z'$: $$\arg{\left(\frac{w'}{z'}\right)} = \arg{(w')} - \arg{(z')}$$ Since this is a conformal mapping, we can use Lemma 2 to claim that the difference of angles between $w'$ and $z'$ is only dependent of $f$ and $z_0$. Since we're assuming these are fixed, we find that $\arg(w'/z')$ is constant.

However, we just claimed above that $w'/z'$ are points in a circle. So the only way their argument can be constant is if the circle has radius 0, that is $\abs{\beta} = 0$ (and so is $\beta = 0$): $$\beta = \frac{z'_x + i z'_y}{2} = 0$$ Substituting $z'_x$ and $z'_y$ from $(4.3)$ we get: $$(4.7) \quad \frac{df}{dx}(z_0) + i \frac{df}{dy}(z_0) = 0$$ If we split $f$ into two functions corresponding to the real and imaginary parts, $f(x, y) = u(x, y) + i v(x, y)$, then $$\frac{df}{dx} = \frac{du}{dx} + i \frac{dv}{dx}$$ and $$\frac{df}{dy} = \frac{du}{dy} + i \frac{dv}{dy}$$ Replacing in $(4.7)$: $$\frac{du}{dx}(z_0) + i \frac{dv}{dx}(z_0) + i \left(\frac{du}{dy}(z_0) + i \frac{dv}{dy}(z_0)\right) = 0$$ Separating the real and imaginary parts: $$\left(\frac{du}{dx}(z_0) - \frac{dv}{dy}(z_0)\right) + i \left(\frac{dv}{dx}(z_0) + \frac{du}{dy}(z_0)\right) = 0$$ From this we can obtain 2 equations, one for the real part and one for the imaginary: $$\frac{du}{dx}(z_0) = \frac{dv}{dy}(z_0), \qquad \frac{dv}{dx}(z_0) = -\frac{du}{dy}(z_0)$$ Which are the Cauchy-Riemann equations! QED.

Examples

One of the simplest conformal mapping is the function $f(z) = z + w$ for a constant $w \in \mathbb{C}$. If we interpret it in the complex plane, the function corresponds to a translation of each point on its domain. It’s not hard to believe that the angles are preserved on translation. In fact, we have $f’(z) = 1$, so it’s never zero and it’s conformal everywhere.

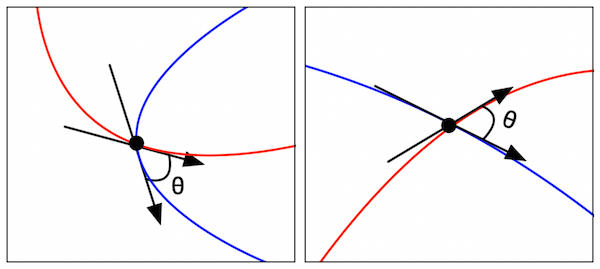

Another example is the function $f(z) = kz$, for a constant $k \in \mathbb{R}$. In the complex plane we can interpret it as a homothety. It’s not quite the same as scaling because there’s also displacement involved, depending on how far points are from the origin. Figure 3 makes it more intuitive:

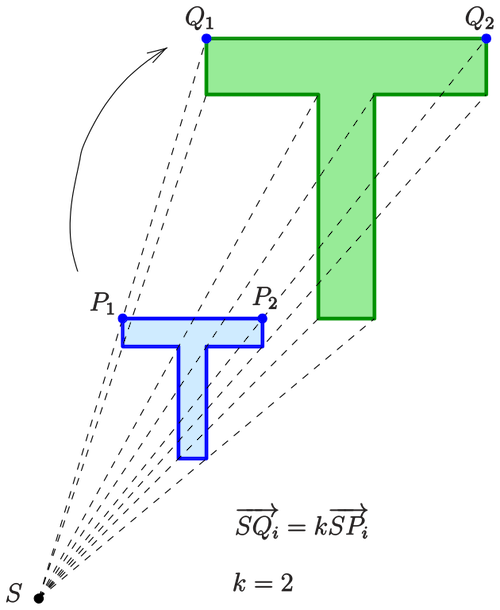

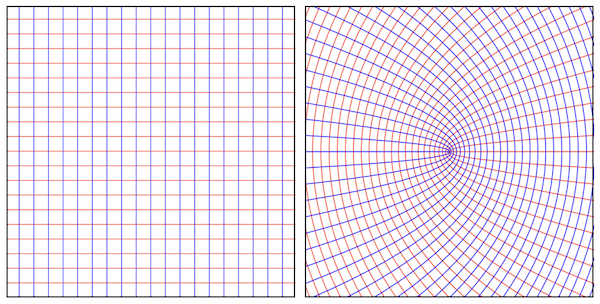

Another interesting example is the function $f(z) = z^2$. It has the derivative $f’(z) = 2z$, so it’s a conformal map except at $z = 0$. It’s hard to visualize what it looks like but we can consider the domain as being horizontal and vertical lines as Figure 4 (left). The corresponding curves after applying $f(z)$ are the “horizontal parabolas” shown in Figure 4 (right).

We can see that at the intersection points on the domain, the blue and red lines intersect at 90 degrees. On the transformed curves, if we consider the tangents at the intersection points, they also have 90 degrees between them, except at $(0, 0)$ where they’re now at 180 degrees. But $f’(0)$ is zero, so $f$ is not conformal there.