kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > The Perron Method

The Perron Method

31 Dec 2025

Oskar Perron was a German mathematician and professor at the University of Heidelberg and then the University of Munich.

Perron had a prolific career in mathematics with 218 publications in several fields. He taught until in 1951 at age 71 but continued teaching until 80 and still doing researching, writing a book in non-Euclidean geometry at age 82 [6].

Perron is also known for providing a relatively simple characterization of a solution to the Dirichlet problem for Laplace’s equations, using subharmonic functions, known as the Perron method, which we explore in this post.

The Dirichlet Problem

The general Dirichlet problem consists in finding a function $f(z)$ with a bounded domain $\Omega$, given we only know its values at the boundary of the domain, $\delta \Omega$.

A special case of this problem is when we require the function to satisfy the Laplace equation, in other words, that the function be harmonic. For the remainder of the post, when we mention the Dirichlet problem we’ll be referring to this specific case.

The Perron method is an algorithm that can be used to determine if the Dirichlet problem has a solution, but not how to find one explicitly.

Definitions

We’ll define some terminology needed for describing the proof. First we assume a function $f$ defined at the boundary $\delta \Omega$. We’ll denote points in this boundary by $\zeta$ instead of $z$, to avoid having to clarify to which set is belongs.

We’ll assume that $f$ is bounded by $M$, i.e. $\abs{f(\zeta)} \le M$. We define the family of functions $\mathcal{B}(f)$ as the set of functions $v$ in $\Omega$ such that:

- $v$ is subharmonic

- $\limsup_{z \rightarrow \zeta} v(z) \le f(\zeta)$, $\zeta \in \delta \Omega$

Notice how $v$ is a “weaker” version of the function $v^*$ we’re looking for, which must be:

- $v^*$ is harmonic

- $\lim_{z \rightarrow \zeta} v(z) = f(\zeta)$, $\zeta \in \delta \Omega$

We observe that $\mathcal{B}(f)$ has at least the same cardinality as the reals because any constant function $v(z) = c$ for $c \le -M$ belongs to it. Next we define the Perron function (I came up with this name for convenience. I don’t think this term is used in the literature).

Definition 1. Let the function $u(z)$ be the lower upper bound of $v(z)$ for $v \in \mathcal{B}(f)$. More precisely, for each $z \in \Omega$, $u(z)$ is the supremum of the set $\curly{v(z) : v \in \mathcal{B}(f)}$. We call this function the Perron function of $f$.

Now Lemma 2 shows that the Perron’s function is harmonic.

Lemma 2. Let $f$ be a function defined for $\delta \Omega$. Perron’s function $u$ of $f$ is harmonic.

Let $D$ be a disk contained in $\Omega$ and $z_0 \in D$. Then there's a sequence of functions $v_n$ in $\mathcal{B}(f)$ such that: $$ (2.1) \quad \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} v_n(z_0) = u(z_0) $$ Let $V_n$ be the function defined as $\max(v_1, v_2(z_0), \dots, v_n(z_0))$ (point-wise). Since the max of two subharmonic function is subharmonic, $V_n$ belongs to $\mathcal{B}(f)$.

Let $V'_n$ be a function that is equal to $V_n$ outside $D$ and equal to the Poisson Integral $P_{V_n}$ of $V_n$ inside $D$ as defined in [2]. It's possible to show that $P_{V_n}$ is harmonic and that $\lim_{z \rightarrow \zeta} P_{V_n} = \lim_{z \rightarrow \zeta} V_n \le f(\zeta)$. Thus $P_{V_n} \in \mathcal{B}(f)$. By Lemma 4 in [2], we also have $V_n(z) \le P_{V_n}(z)$.

Since $V_n$ equals to one of $v_n \in \mathcal{B}(f)$, $V'_n$ belongs to $\mathcal{B}(f)$ as well, both inside and outside $D$. From our choice of $u$ we have that: $$ (2.2) \quad V'_n(z) \le u(z) $$ We thus have this set of inequalities: $$ v_n(z_0) \le V_n(z_0) \le V'_n(z_0) \le u(z_0) $$ From $(2.1)$ we get that $$ (2.3) \quad \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} V'_n(z_0) = u(z_0) $$ The Harnack principle claims that a sequence of harmonic functions converges to a harmonic function. Since $V'_n$ is harmonic in $D$, the sequence $\curly{V'_n}$ converges to some harmonic function $U$ in $D$. From $(2.2)$ we get $U(z) \le u(z)$ with $U(z_0) = u(z_0)$ from $(2.3)$.

Now we choose another point $z_1$ in $D$ and find a sequence of functions $w_n \in \mathcal{B}(f)$ with $$ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} w_n(z_1) = u(z_1) $$ and then define $\overline{w}_m = \max(v_n, w_n)$. If we proceed with the same argument as we did for $v_n$, we arrive at the harmonic function $U_1 \le u$ and $U_1(z_1) = u(z_1)$. And since $U_1$ is constructed from $\overline(w_n) \ge u_n$, we have $U \le U_1$.

Consider $U - U_1$ which is harmonic. We have $U - U_1 \le 0$ and $U(z_0) = U_1(z_0)$. This means this function attains 0 at an interior point $z_0$ and since it cannot be larger than 0, it must be a constant. This implies $U = U_1$ in $D$. Since we picked arbitrary points $z_0$ and $z_1$, this holds for any point in $z \in D$ and thus $U(z) = u(z)$, and since this holds for any disk inside $\Omega$, this holds for $\Omega$. So $U$ is $u$ and $u$ is harmonic. QED.

Perron’s Function is a Solution

The Dirichlet problem doesn’t always have a solution. One example provided in [1] is where the domain $\Omega$ consists of a punctured disk $0 \lt \abs{z} \lt 1$ with boundary values $f(0) = 1$ and $f(\zeta) = 0$ at the circumference $\abs{\zeta} = 1$.

It’s possible to show that like holomorphic functions, harmonic functions can be extended to remove some types of singularities such as this example. This means the problem can be reduced to finding a harmonic function at a disk with $f(\zeta) = 0$ at the circumference $\abs{\zeta} = 1$ and equal to 1 at the origin.

Due to the maximum principle, harmonic functions must attain its maximum at the boundary, which cannot be done here since in the boundary it’s equal to 0 but there’s a point inside on which it’s valued at 1. So no harmonic function satisfy these constraints and hence this problem has no solution.

As Lemma 3 shows however, is that if the problem has a solution, then the Perron function is one such solution.

Lemma 3. If the Dirichlet problem with boundary values defined by $f$ has a solution, then Perron’s function $u$ is a feasible solution.

Conditions for Solutions

We now know that if the Dirichlet problem has a solution, the Perron function is one of them. In this section we provide sufficient conditions for a solution to exist. In [1] the author argues that sufficient and necessary conditions are known but not very practical and that the necessary one we’ll cover now, works well in practice.

First we define the concept of a barrier.

Definition 4. Let $w(z)$ in $\Omega$ be a harmonic function which at the boundary $\delta \Omega$ is continuous and strictly positive except at the point $\zeta_0$ at which it’s 0. We denote this function a barrier at $\zeta_0$.

We now prove an intermediate Lemma connecting barriers and Perron’s function:

Lemma 5. Let $\Omega$ be a region and $f$ be a function defined at $\delta \Omega$ and bounded by $M$ and $u$ the Perron function for $f$. If there exists a barrier $w$ at $\zeta_0$ then

\[\lim_{z \rightarrow \zeta_0} u(z) = f(\zeta_0)\]For the first part, we define a neighborhood $N$ of $\zeta_0$ (contained in $\delta \Omega$) where this holds: $\abs{f(\zeta) - f(\zeta_0)} \lt \epsilon$ for $\zeta \in N$. Let $w_0$ be the minimum value of $w$ in $\delta \Omega \setminus N$. Since it doesn't contain $w(\zeta_0)$, this $w_0 \gt 0$.

We define the function $W$ as: $$ (5.1) \quad W(z) = f(\zeta_0) + \epsilon + \frac{w(z)}{w_0} (M - f(\zeta_0)) $$ for $z \in \Omega$. Note that all terms but $w(z)$ are constant on the right hand side. Since $w(z)$ is assumed harmonic and harmonic functions are closed under their scalar multiplication, $W(z)$ is also harmonic.

If $\zeta \in N$, since $w(\zeta)$ and $w_0$ are non-negative, the fraction is non-negative and obviously $M \ge f(\zeta_0)$ so we have: $$ W(\zeta) \ge f(\zeta_0) + \epsilon $$ Since we're inside $N$, $\abs{f(\zeta) - f(\zeta_0)} \lt \epsilon$ then $f(\zeta_0) + \epsilon \gt f(\zeta)$ and thus: $$ W(\zeta) \gt f(\zeta) $$ Now if $\zeta$ in $\delta \Omega \setminus N$, then $w(\zeta) \ge w_0$ and $w(\zeta) / w_0 \ge 1$, so $(5.1)$ becomes $$ W(\zeta) \ge f(\zeta_0) + \epsilon + M - f(\zeta_0) = M + \epsilon \gt f(\zeta) $$ We conclude that for $\zeta \in \delta \Omega$, $W(\zeta) \gt f(\zeta)$. For any $v \in \mathcal{B}(f)$, they satisfy $\limsup_{z \rightarrow \zeta} v(z) = f(\zeta) \lt W(\zeta)$. Since they subharmonic and $W$ is harmonic, having $\limsup_{z \rightarrow \zeta} v(\zeta) \lt W(\zeta)$ implies that $v(z) \lt W(z)$ for $z \in \Omega$.

Thus Perron's function satisfies $u(z) \le W(z)$. In particular $\limsup_{z \rightarrow \zeta_0} u(z) \le W(\zeta_0)$. From $(5.1)$ we have $W(\zeta_0) = f(\zeta_0) + \epsilon$ (since $w(\zeta_0) = 0$) and thus $\limsup_{z \rightarrow \zeta_0} u(z) \le f(\zeta_0) + \epsilon$ which concludes the first part of the proof.

For the second part we define an analogous auxiliary function $V(z)$: $$ (5.2) \quad V(z) = f(\zeta_0) - \epsilon - \frac{w(z)}{w_0} (M + f(\zeta_0)) $$ This function is also harmonic. For $\zeta in N$, the fraction $w(z) / w_0$ is non-negative and thus $$ V(\zeta) \le f(\zeta_0) - \epsilon $$ Since $\zeta in N$ we have $f(\zeta_0) - \epsilon \lt f(z)$, and so $V(\zeta) \lt f(\zeta)$. For $\zeta$ in $\delta \Omega \setminus N$, the fraction $w(z) / w_0 \ge 1$ and thus $(5.2)$ becomes: $$ V(z) le f(\zeta_0) - \epsilon - (M + f(\zeta_0)) = - (M + \epsilon) \lt f(\zeta) $$ we conclude that $V(\zeta) \lt f(\zeta)$ for $\zeta \in \delta \Omega$. Since $V(z)$ is harmonic, it is continuous and $\lim_{z \rightarrow \zeta} V(z) = V(\zeta) \lt f(\zeta)$. This means $V$ satisfies the conditions to be in $\mathcal{B}(f)$.

By the definition on Perron's function, $u(z) \ge V(z)$ and $\liminf_{z \rightarrow \zeta} u(z) \ge V(\zeta)$. In particular for $\zeta_0$, we have from $(5.2)$ that $V(\zeta_0) = f(\zeta_0) - \epsilon$ and thus $\liminf_{z \rightarrow \zeta} u(z) \ge f(\zeta_0) - \epsilon$, which completes the proof.

Now if there’s a barrier at each point $\zeta \in \delta \Omega$, we have $\lim_{z \rightarrow \zeta} u(z) = f(\zeta)$. Since $u$ is harmonic (Lemma 2), Perron’s function is a solution. In other words, a sufficient condition for the Dirichlet problem to have a solution is that we can find the appropriate barrier functions.

So barrier is this sort of “tracks” which does not directly relate to the solution but they provide evidence a solution exists. Also notice that the barrier function is independent of $f$, it only depends on the region $\Omega$.

Examples of Barriers

Now we consider two examples of barriers.

Let $\Omega \cup \delta \Omega$ be contained in an open half plane (determined by a line $\ell$), except for a single point $\zeta_0$ (in $\delta \Omega$) that lies in $\ell$. Suppose the direction of the line is $\alpha$ and the half plane lies to the left of $\ell$. Lemma 6 shows that there exists a barrier for $\zeta_0$.

Lemma 6. The function $w(z) = \Im \left(e^{-i\alpha} (z - \zeta_0)\right)$ is a barrier at $\zeta_0$

Further, we have $w(\zeta_0) = 0$. The transform first translates the half plane to that $\zeta_0$ is now the origin and then it rotates it by $\alpha$ clockwise so that $\ell$ is the $x$-axis. Now all points except $\zeta_0$ lie above the $x$-axis, and thus positive imaginary part and hence $w(z) \gt 0$.

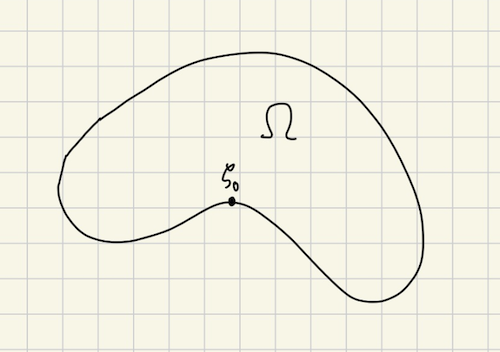

There’s nothing special on our choice of $\zeta_0$ so we could use a family of such functions for each $\zeta \in \delta \Omega$. While a very simple function, the limitation with this approach is that for each point $\zeta$ we need to find a line that goes through $\zeta$ but doesn’t cut through the region. This might not be possible depending on the “shape” of the region, for example Figure 1.

A more flexible option is to find a line segment that is external to $\Omega$ except for one of its endpoints $\zeta_0$ lying in $\delta \Omega$. If we find one, then Lemma 7 shows there exists a barrier for $\zeta_0$.

Lemma 7. Let $\Omega$ be a region and $\ell$ a line segment with endpoints $\zeta_0$ and $\zeta_1$ such that only $\zeta_0$ lies in $\delta \Omega$ and the rest of the segment is external to $\Omega$. Then there exists a function

\[(1) \quad w(z) = \Im \left(e^{-i\alpha} \sqrt{\frac{z - \zeta_0}{z - \zeta_1}}\right)\]for some real $\alpha$, which is a barrier at $\zeta_0$.

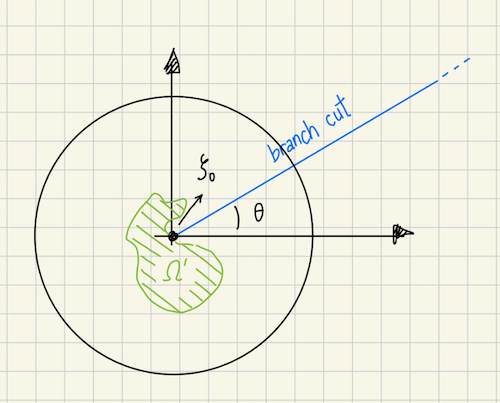

This ray does not intercept $\Omega$ except at the new origin. Thus the region $\Omega$ must be somewhere in the extended complex plane $\mathbb{C}$ minus the points in ray.

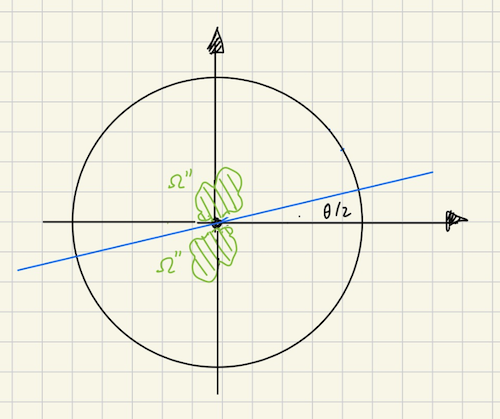

Next we take the square root of that result. Recall that the square root is multi-valued so we need to deal with branch cuts and branches [5]. We can use the ray is the branch cut, because since $\Omega$ does not intercept the ray except at the origin, we guarantee it will be cointained within a single branch of the square root.

This branch is effectively a half-plane, so with this transform we reduced the original to a region that can be solved with the simpler approach, which consists in rotating clockwise by $\alpha = \theta/2$. Thus we have that $\Omega$ in this transformed domain now lies exclusively above the $x$-axis, with the exception of the original point $\zeta_0$ which is now at the origin, so the imaginary part will be positive for $z \in \delta \Omega$ except at $\zeta_0$ where it's 0.

Again, there’s nothing special about $\zeta_0$ and $\zeta_1$. We just need to find a proper line segment, which is much easier than finding a half-plane. We can now state more relaxed conditions for the Dirichlet to have a solution:

Corollary 8. The Dirichlet problem has a solution for a region $\Omega$ if, for each point $\zeta_0$ at the boundary $\delta \Omega$ there is a line segment external to $\Omega$ except for one endpoint at $\zeta_0$.

Conclusion

Perron’s method is very clever. I wonder what the process at coming up with Perron’s function and barriers was. In the book The Music of the Primes, the author mentions that mathematicians keep the scaffolding they used to arrive at a result secret, which makes the final result look like magic.

I don’t have a good intuition on barriers, except that they’re used as some sort of clue to find Perron’s function. From the example barriers provided in [1], it reminds me of machine learning techniques for classification problems, in which you need to find hyperplanes with hopes that data belonging to different classes end up on different sides of the plane.

As usual Ahlfors’ geometry intuition for the second barrier example is “$(1)$ is easily seen to be a barrier”. I had to do some probing with ChatGPT to be able to prove it is indeed a barrier.