kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Subharmonic Functions

Subharmonic Functions

14 Dec 2025

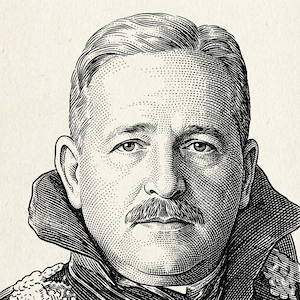

Frigyes Riesz was a Hungarian mathematician. He was born in Győr in 1880, then part of Austro-Hungarian Empire, and today’s Hungary. He was a professor at Franz Joseph University of Kolozsvár.

After the Treaty of Trianon, in which portions of the kingdom of Hungary went to its neighbors, Kolozsvár became part of Romania and renamed Cluj. The University moved to Szeged, becoming known as Szeged University where Riesz continued to lecture. The one in Cluj was renamed to Dacia Superior University, but today is called Babeș-Bolyai University.

Frigyes is considered one of the founders of functional analysis and has many theorems named after him, such as the Riesz–Fischer theorem and the F. and M. Riesz theorem, which is also named after his brother Marcel Riesz. One of the concepts Riesz came up with is the subharmonic functions, which we study in this post.

Intuition

Recall that harmonic functions [2] are defined as:

\[\Delta f = \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y^2} = 0\]If we restricted this equation to one dimension, it would be:

\[\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} = 0\]If we integrate twice, we get back a function $u(x) = Ax + B$, which is a linear function. If the domain of this function is the inverval $[a, b]$ and if we’re given $u(a)$ and $u(b)$, we can compute $u(x)$, in the same way a harmonic function in 2-dimensions can be calculated from the boundary of its domain.

In 1-dimension, let $f$ and $u$ be functions in the domain $[a, b]$ with $u(a) = f(a)$ and $u(b) = f(b)$, with $u(x)$ being a linear function. Then $f$ is called convex if it doesn’t exceed $f(x) \le u(x)$, for example:

Note that in this definition the linear function $u(x)$ itself is considered a convex function (it’s also concave) which is thus a more general property than linear functions.

If we generalize this to 2-dimensions, the linear function becomes a harmonic function and the convex function will be defined as a subharmonic function.

Definition

We can formalize the intuition described above.

Definition 1. Let $v(z)$ be a real-value continuous function defined in a region $\Omega$. Then $v(z)$ is subharmonic in $\Omega$ if, for every harmonic function $u(z)$ in $\Omega’ \subset \Omega$, having $v(z) \le u(z)$ for $z \in \partial \Omega’$ implies $v(z) \le u(z)$ for $z \in \Omega’$.

In other words, if $v$ is subharmonic, and it doesn’t exceed an harmonic function $u$ at the boundary of its domain, then it doesn’t exceed it inside the domain either.

An equivalent definition that will be more useful later is the following:

Lemma 2. Let $v(z)$, be a real-value continuous function defined in a region $\Omega$. If, for every harmonic functions $u(z)$ in $\Omega’ \subset \Omega$ the function $v - u$ satisfies the maximum principle in $\Omega’$, then $v$ is subharmonic.

Note: I’m only able to prove this if not satisfying the maximum principle means there’s a point $z \in \Omega’$ such that $v(z) - u(z) \gt v(w) - u(w)$ for $w \in \partial \Omega’$, that is, strictly greater as opposed to $v(z) - u(z) \ge v(w) - u(w)$.

If $v(z_1) \gt u(z_1)$ for some $z_1 \in \Omega'$, i.e. $v(z_1) - u(z_1) \gt 0$, then there's a path between two points in the boundary that goes through $z_1$. Since it changes direction, there must be a point with derivative $0$ and hence $v - u$ has a maximum for that path. If we consider all possible paths and take the maximum of the maximum, we'll arrive at a contradiction.

Now suppose $v - u$ does not satisfy the maximum principle. We need to prove there exists some harmonic function for which, when $v(z) \le u(z)$ for $z \in \partial \Omega'$ there's $z \in \Omega'$ such that $v(z) \gt u(z)$.

Since we're assuming $v - u$ does not satisfy the maximum principle, then there's $z_0$ for which $v - u$ attains the maximum in $\Omega'$. Let $c = v(z_0) - u(z_0)$. Suppose that $v(z) \le u(z)$ for $z \in \partial \Omega'$. If $c \gt 0$, we found that $v(z) \gt u(z)$ for $z_0 \in \Omega'$.

Otherwise, suppose $c \le 0$. Since $c$ is the maximum value attained by $v(z) - u(z)$, we have $v(z) \le u(z) - \abs{c}$ for $z \in \Omega' \cup \partial \Omega'$ . Let $h = u - \abs{c} - \epsilon$ for $\epsilon \gt 0$. Since $u$ is harmonic and harmonicity is closed under subtraction, so is $h$.

Since we're assuming $v(z) - u(z) \gt v(w) - u(w)$ for $w \in \partial \Omega'$, with a sufficiently small $\epsilon$ we still have $v(w) \le h(w)$ for some $w \in \partial \Omega'$. And now we have $c = v(z_0) - h(z_0) \gt 0$.

So either $u$ is the harmonic function we were looking for, or if not, we can find some other $h$ that is.

Properties

Corollary 3. Every harmonic function is subharmonic.

This follows from Definition 1 since if we replace $v$ by $u$ it satisfies the equations on the equality.

There’s an analogous definition of superharmonic function which we’ll not discuss, but it’s possible to show that a function that is both subharmonic and superharmonic is harmonic.

Before we continue, let’s introduce the Poisson Integral. For any continuous function $U(\theta)$ for $0 \lt \theta \lt 2 \pi$ we can define the Poisson Integral as:

\[P_U(z) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} \Re \left[ \frac{z_0 + re^{i\theta} + z}{z_0 + re^{i\theta} - z} \right] U(\theta) d\theta\]Now let $v$ be a subharmonic function in $\Omega$ and let $D$ be a disk of radius $r$ and center $z_0$ contained in $\Omega$. Suppose $U$ is defined to be equal to $v$ at the circumference of the disk, that is $U(\theta) = v(z_0 + re^{i\theta})$. We can denote it by $P_v(z)$ as:

\[(1) \quad P_v(z) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} \Re \left[ \frac{z_0 + re^{i\theta} + z}{z_0 + re^{i\theta} - z} \right] v(z_0 + re^{i\theta}) d\theta\]It’s possible to show the Poisson integral is a harmonic function and that $\lim_{z \rightarrow w_0} P_v(z) = v(w_0)$. With these, Lemma 4 shows that $v(z) \le P_v(z)$ inside $D$.

Lemma 4. Let $v$ be a subharmonic function and $P_v(z)$ be the Poisson integral as defined in $(1)$ for a disk $D$ centered in $z_0$. Then

\[v(z) \le P_v(z)\]for $z \in D$.

Note: It might seem that Lemma 4 follows directly from Definition 1, if we replace $\Omega’$ with $D$ and $u$ with $P_v$, since it seems to be that $v(z) = P_v(z)$ in $\delta D$ (i.e. the circumference of the disk), but $P_v$ is not defined in $\delta D$, so we need a different approach. But as we can see, having $\lim_{z \rightarrow w} P_v(z) = v(z)$ for $w \in \delta D$ also suffices.

Lemma 5. A continuous function $v(z)$ is subharmonic in $\Omega$ if it satisfies:

\[(2) \quad v(z_0) \le \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} v(z_0 + re^{i\theta}) d\theta\]for every disk $\abs{z - z_0} \le r$ contained in $\Omega$.

For the other direction, Lemma 4 shows that $v(z) \le P_v(z)$. For $z = z_0$ we have $r = 0$, which replacing in $(1)$ gives us: $$ P_v(z_0) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} \Re \left[ \frac{z_0 + re^{i\theta}}{z_0 + re^{i\theta}} \right] v(z_0 + re^{i\theta}) d\theta = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} v(z_0 + re^{i\theta}) d\theta $$ since $v(z_0) \le P_v(z_0)$, we arrive at $(2)$.

Lemma 6. If the Laplacian of a function is greater or equal than 0 everywhere, then it’s subharmonic.

Unless the function is constant, around this "peak" the function must have a negative second derivative. An intuition is to think in terms of physics: if the function represents the height of an object, the 2nd derivative is the acceleration. If the function changes direction around the "peak", it must come to a stop (decelerate) before "turning".

We thus have $$ \frac{\partial^2 (v - u)}{\partial x^2} \lt 0, \qquad \frac{\partial^2 (v - u)}{\partial y^2} \lt 0 $$ at some point $z_0$. The Laplacian of $v - u$ is: $$ \Delta(v - u) = \frac{\partial^2 (v - u)}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 (v - u)}{\partial y^2} $$ which is negative at $z$. Since the Laplacian is a linear function and $\Delta u = 0$ everywhere because it's harmonic, it follows $\Delta v \lt 0$ for $z_0$.

Note that a positive Laplacian if $v$ implies that $v$ is subharmonic but the other way around. However, if $v$ has partial derivatives of first and second orders, it’s possible to show this other direction is also true.

From Lemma 5, because integrals has the linearity property we can conclude that:

Corollary 7. Let $v$ be a subharmonic function and $k \ge 0$ a scalar. Then $kv$ is subharmonic.

Note that if $k \lt 0$ it doesn’t work because it changes the inequality $(2)$.

Corollary 8. Let $v_1$ and $v_2$ be subharmonic functions. Then $v_1 + v_2$ is subharmonic.

Similarly, this doesn’t necessarily hold for $v_1 - v_2$ because of the inequality sign.

Lemma 9. Let $v_1$ and $v_2$ be subharmonic functions. Then $\max(v_1, v_2)$ is subharmonic.

Since we're assuming $v$ is not subharmonic, by Lemma 2 there is some harmonic function $u$ such that $v - u$ has a maximum at $z_0$. Now, without loss of generality, assume $v(z_0) = v_1(z_0)$. We then have, for all $z$: $$ v_1(z) - u(z) \le v(z) - u(z) \le v(z_0) - u(z_0) = v_1(z_0) - u(z_0) $$ This implies that $v_1 - u$ has a maximum at $z_0$ too. Since we're assuming $v_1$ is subharmonic, it can only be that it is constant. This in turn implies all the inequalities above are equalities: $$ v_1(z) - u(z) = v(z) - u(z) = v(z_0) - u(z_0) = v_1(z_0) - u(z_0) $$ in particular that $v(z) - u(z) = = v(z_0) - u(z_0)$ implying it is constant, which contradicts the assumption it has a maximum. QED.

Lemma 10. Let $v$ be a subharmonic function in $\Omega$, $D$ be a disk contained in $\Omega$ and $P_v$ the Poisson integral as defined in $(1)$. Let’s define the function $v’$ as:

\[\begin{equation} v'=\left\{ \begin{array}{@{}ll@{}} P_v, & v \in D \\ v, & v \in \Omega \setminus D \end{array}\right. \end{equation}\]Then $v’$ is also subharmonic.

Since $P_v$ is harmonic and by Corollary 3 also subharmonic, and since $v$ is subharmonic then $v'$ should be subharmonic in $\Omega$.

In Alfhors, it's also explicitly shown that $v'$ is subharmonic at $\delta D$ but my understanding is that in there, $v' = v$, which is subharmonic, so I'm do not follow why a special treatment is needed.

Conclusion

I found the concept of subharmonic and superharmonic functions as the half parts of a harmonic function interesting. This same pattern can be seen with convex and concave functions which together form a linear function, or that $a \le b$ and $a \ge b$ together imply $a = b$.

The book also mentions that continuity is not strictly necessary to work with subharmonic functions: we can relax it to upper semi-continuous functions. The counterpart of upper semi-continuous functions are the lower semi-continuous functions and like the examples above, a function that is both upper and lower semi-continuous is continuous.

References

- [1] Complex Analysis - Lars V. Ahlfors

- [2] NP-Incompleteness: Harmonic Functions