kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Weierstrass Factorization Theorem

Weierstrass Factorization Theorem

02 Jul 2025

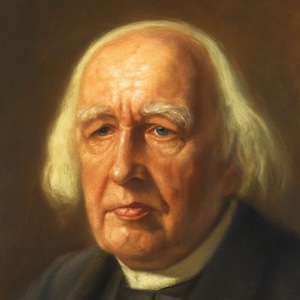

Karl Weierstrass was a German mathematician often regarded as the father of modern analysis. Despite being the author of groundbreaking theorems, Weierstrass never finished college.

The University of Königsberg eventually granted him a honorary degree and he became a professor at the nowadays Humboldt Universität zu Berlin.

Weierstrass tutored Sofia Kovalevskaya (the same woman Mittag-Leffler helped become full professor in Sweeden [6]), regarding her his best student, and helped her get a doctorate from Heidelberg University.

In this post we’ll study the Weierstrass Factorization Theorem which allows us to express an entire function as a product of its zeros.

Infinite Products

Before we start, we need to introduce the concept of infinite products. Let $p_n$ be a (possibly infinite) set of complex numbers. We can denote their product as:

\[(1) \quad P = \prod_{k=1}^\infty p_k\]We can define a partial product as:

\[P_n = \prod_{k=1}^n p_k\]We can say that an infinite product converges if its partial products, excluding terms equal to 0, tend to a finite limit other than 0.

It must be that $\abs{p_k} \rightarrow 1$ because $P_k \rightarrow P_{k+1}$ and $p_k = P_{k+1}/P_k$. If we define $a_k = p_k - 1$, then it must be that $\abs{a_k} \rightarrow 0$.

Let’s take the logarithm of $(1)$ to obtain a series:

\[S = \sum_{k=1}^\infty \ln (1 + a_k)\]We need to be careful with the logarithm because for complex numbers it’s a multi-valued function [2]. To make this precise, for each term of the sum, we choose the principal branch of the logarithm and denote it by $\mbox{Log}$:

\[\mbox{Log}(z) = \ln \abs{z} + i \arg{z}, \quad \arg(z) \in (-\pi, \pi]\]As Lemma 1 shows $(1)$ and $(2)$ converge simultaneously.

Lemma 1. Let $p_n$ be a (possibly infinite) set of complex numbers, $a_n = p_n - 1$. Let $\mbox{Log}(z)$ be the principal branch of $\ln(z)$. Then

\[P = \prod_{k=1}^\infty p_k\]converges if and only if

\[(2) \quad S = \sum_{k=1}^\infty \mbox{Log} (1 + a_k)\]converges.

Now assume $(1)$ converges, that is, $$(1.1) \quad \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} P_n = P$$ with $P \ne 0$. If we were dealing with real numbers, we could apply $\ln$ to both sides and arrive at $$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{k = 1}^n \ln(1 + a_k) = \ln(P)$$ and find that $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} S_n = S$. But again, $\ln$ is a multi-valued function and it's not necessarily true that $$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{k = 1}^n \mbox{Log}(1 + a_k) = \mbox{Log}(P)$$ Because the sum of the principal branches could yield a different branch of $\ln$. So more care is needed. While we can't guarantee they're the same branch, we know that two branches differ by $k 2 \pi i$ for some integer $k$, so we have $$(1.2) \quad \mbox{Log}(P_n) = S_n + h_n 2 \pi i$$ for $h_n \in \mathbb{Z}$. Consider the quotient $P_n / P$ and apply $\mbox{Log}$: $$\mbox{Log}(P_n / P) = \mbox{Log}(P_n) - \mbox{Log}(P)$$ replace $(1.2)$ to obtain: $$(1.3) \quad \mbox{Log}(P_n / P) = S_n + h_n 2\pi i - \mbox{Log}(P)$$ If we repeat for $P_{n + 1} / P$ we get: $$\mbox{Log}(P_{n+1} / P) = S_{n+1} + h_{n+1} 2\pi i - \mbox{Log}(P)$$ Now subtract one from another: $$\mbox{Log}(P_{n+1} / P) - \mbox{Log}(P_{n+1} / P) = \mbox{Log}(1 + a_n) + (h_{n+1} - h_n) 2 \pi i$$ Exponentiating and looking at the argument of the result gives us: $$\arg(P_{n+1} / P) - \arg(P_{n} / P) = \arg(1 + a_n) + (h_{n+1} - h_n) 2 \pi$$ as $n \rightarrow \infty$, $P_n \rightarrow P_{n+1}$, so the lefthand side vanishes and we're left with: $$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \arg(1 + a_n) + (h_{n+1} - h_n) 2 \pi = 0$$ Our choice of $\mbox{Log}$ is such that the argument of its result is within $(-\pi, \pi]$ and since $(h_{n+1} - h_n)$ must be an integer, the only way for this to true is if $h_{n+1} = h_n$. Let $h = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} h_n$. If we take the limit $n \rightarrow \infty$ for $(1.3)$, we have: $$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \mbox{Log}(P_n / P) = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} S_n + h_n 2\pi i - \mbox{Log}(P)$$ Since $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} P_n \rightarrow P$ (hypothesis), $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} P_n / P = 1$ and thus $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \mbox{Log}(P_n / P) = 0$. We thus have: $$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} S_n + h 2\pi i - \mbox{Log}(P) = 0$$ or $$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} S_n = \mbox{Log}(P) - h 2\pi i$$ we can conclude that if $(2)$ converges to $P$, then $(1)$ converges to some branch of $\ln(P)$. QED.

Another result regarding absolute convergence is provided by Lemma 2:

Lemma 2. Let $p_n$ be an infinite set of complex numbers, $a_n = p_n - 1$, with $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \abs{a_n} = 0$. Let $\mbox{Log}(z)$ be the principal branch of $\ln(z)$. Then

\[(3) \quad \sum_{k = 1}^\infty \abs{\mbox{Log} (1 + a_n)}\]and

\[(4) \quad \sum_{k = 1}^\infty \abs{a_n}\]converge simultaneously.

The sum $(3)$ is composed of a finite part + $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} S_n$ and $(4)$ of some other finite part + \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} A_n$, so if $(3)$ converges, $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} S_n$ exists and so does $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} A_n$ and $(3)$ converges. The contrary applies too.

The combination of Lemma 1 and Lemma 2 leads to:

Corollary 3. Let $p_n$ be a (possibly infinite) set of complex numbers, $a_n = p_n - 1$. Then the product:

\[P = \prod_{k=1}^\infty p_k\]converges absolutely if

\[\sum_{k = 1}^\infty \abs{a_n}\]converges.

Entire Functions

An entire function is a function that is holomorphic in the entire complex plane. Examples include polynomials, the exponential function and some trigonometry functions such as $\sin(z)$.

We’ll now decompose an entire function based on its zeros. We start with the simple case where $f(z)$ has no zeros.

Lemma 4. $f(z)$ is a non-zero entire function if and only if $f(z) = e^{g(z)}$ for some entire function $g(z)$.

For the other direction, assume $f(z)$ is an entire function without zeros. Since the derivative of a holomorphic function is also holomorphic, $f'(z)$ is an entire function. Since $f(z) \ne 0$, $f'(z) / f(z)$ is also an entire function. This means it's the derivative of some other entire function $g(z)$ [3], that is: $$ (4.1) \quad g'(z) = f'(z) / f(z) $$ Now define: $$ h(z) = f(z) e^{-g(z)} $$ Since $f(z)$ and $g(z)$ are entire, so is $h(z)$, so its derivative exists: $$ h'(z) = f'(z) e^{-g(z)} - f(z) g'(z) e^{-g(z)} $$ Replacing $(4.1)$ and simplying: $$ = f'(z) e^{-g(z)} - f'(z) e^{-g(z)} = 0 $$ This means $h(z)$ is a constant function, say $k$. So $$ f(z) = h(z) e^{g(z)} = k e^{g(z)} $$ Where we can absorb $k$ into the function $g(z)$, yielding $$ f(z) = e^{g(z)} $$ QED.

Now we assume that $f(z)$ has zeros, possibly an infinite number of them. First we consider the case where the zeros converge absolutely:

Lemma 5. Let $f(z)$ be an entire function with $m$ zeros at the origin and the other zeros $a_1, a_2, \dots$ (if a zero has order $k$, it repeats $k$ times) and such that

\[(5) \quad \sum_{k = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{\abs{a_k}}\]converges. Then $f(z)$ can be written as:

\[(6) \quad f(z) = z^m e^{g(z)} \prod_{k = 1}^\infty \left(1 - \frac{z}{a_k}\right)\]Now assume the number of zeros is infinite, but satisfy $(5)$. We then need to prove that $$\prod_{k = 1}^\infty \left(1 - \frac{z}{a_k}\right)$$ is convergent. Consider some $z$ with $\abs{z} = R$ and define $b_k = -r/a_k$. We have: $$\prod_{k = 1}^\infty \left(1 - \frac{z}{a_k}\right) = \prod_{k = 1}^\infty \left(1 + b_k\right)$$ According to Lemma 2, this product is absolutely convergent if and only if $$\sum_{k = 1}^\infty \abs{b_k} = r \sum_{k = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{\abs{a_k}}$$ converges. QED.

In case it’s not convergent, we need to add some “dampening” factors in the form of $e^{p(z)}$ (for some polynomial $p(z)$), and we get the more general result known as the Weierstrass Factorization Theorem:

Theorem 6. Let $f(z)$ be an entire function with $m$ zeros at the origin and the other zeros $a_1 \le a_2 \le \dots$ (if a zero has order $k$, it repeats $k$ times) with $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \abs{a_n} = \infty$. Then it can be written as:

\[(7) \quad f(z) = z^m e^{g(z)} \prod_{n = 1}^\infty \left(1 - \frac{z}{a_n}\right) e^{p_n(z)}\]where $p_n(z)$ is the polynomial:

\[(8) \quad p_n(z) = \sum_{k = 1}^{m_n} \frac{1}{k} \left(\frac{z}{a_n}\right)^{k}\]for some non-zero entire function $e^{g(z)}$ and some integer $m_n$ associated with each $a_n$.

We start by applying $\mbox{Log}$ to each term $(1 - z/a_n) e^{p_n(z)}$ and defining it as $r_n(z)$: $$ (6.1) \quad r_n(z) = \mbox{Log}_n \left(1 - \frac{z}{a_n}\right) + p_n(z) $$ Where $\mbox{Log}_n$ denotes the logarithm branch such that $\arg(r_n(z))$ lies within $(-\pi, \pi]$ (notice that different $r_n$'s could use different branches).

Since we assume $\abs{a_n} \gt R$, $w = z / a_n \lt 1$ and the expression $\log(1 - w)$ for $\abs{w} \lt 1$ in any branch, has the Taylor expansion $$ (6.2) \quad \log(1 - w) = - \sum_{k = 1}^\infty \frac{w^k}{k} $$ if we make $p_n(z)$ be the first $m_n$ terms of this expansion, negated, that is $$ p_n(z) = \sum_{k = 1}^{m_n} \frac{w^k}{k} $$ then $r_n(z)$ is the $(6.2)$ without its first $m_n$ terms: $$ r_n(z) = - \sum_{k = m_n + 1}^{\infty} \frac{w^k}{k} $$ intuitively, we're removing the largest terms from the sum, because since $w \lt 1$, higher powers yield smaller values. We now want to find an upperbound for $\abs{r_n(z)}$. Since $k \ge m_n$ in the sum, $1/k \le 1/{m_n}$: $$ \abs{r_n(z)} = \sum_{k = m_n + 1}^{\infty} \frac{\abs{w}^k}{k} \le \frac{1}{m_n + 1} \sum_{k = m_n + 1}^{\infty} \abs{w}^k $$ Since $\abs{w} \lt 1$, the sum is a geometric series that converges to $\abs{w}^{m_n + 1} / \abs{1 - w}$. Replacing $w$ by its definition and using $\abs{z} = R$, $$ \abs{r_n(z)} \le \frac{1}{m_n + 1} \left(\frac{R}{\abs{a_n}}\right)^{m_n + 1} \left(1 - \frac{R}{\abs{a_n}}\right)^{-1} $$ Because $a_n$ is sorted, $w \le r / \abs{a_1} = \alpha$ and thus $1 / (1 - w) \le 1 / (1 - \alpha)$, which is a constant, $$ \abs{r_n(z)} \le \frac{1}{1 - \alpha} \frac{1}{m_n + 1} \left(\frac{R}{\abs{a_n}}\right)^{m_n + 1} $$ Now the question is: can we choose $m_n$ to make sure that $$ S = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{m_n + 1} \left(\frac{R}{\abs{a_n}}\right)^{m_n + 1} $$ converges? The answer is yes. We can set $m_n + 1 = n$ and show that it converges. Let $\alpha = r / \abs{a_1}$ and since we assume $a_n$ is sorted, we have $r / \abs{a_n} \le \alpha$. We then have: $$ \abs{S} \le \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{n} \alpha^{n} $$ Since $\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \alpha^{n}$ converges ($\alpha \lt 1$) and the sequence $\curly{1/n}$ is bounded, the series converges by Abel's test. Note that we found the existence of some set of $m_n$ for which convergence happens, but it's not the only set.

Since $\alpha \abs{S}$ is an upper bound for $\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \abs{r_n(z)}$, we have that is converges too. If we define $b_n(z) = (1 - z/a_n) e^{p(z)}$, then $r_n(z) = \mbox{Log}(b_n(z))$ and from Lemma 1 the sum $$ \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \mbox{Log}(b_n(z)) $$ and the product $$ \prod_{n = 1}^\infty b_n(z) $$ converge simultaneously. Given some radius $r$, this holds for any $z$ inside the circle $\abs{z} \le R$.

One interpretation of Weierstrass Factorization Theorem is that for any set of zeros we can find an entire function that has exactly those zeros.

Meromorphic Functions

Now suppose we have a meromorphic function $f(z)$ with poles $p_1, p_2, \dots$. From Theorem 6 we know there exists an entire function $g(z)$ with $p_1, p_2, \dots$ as zeros.

Around a given pole $p_k$, $f(z)$ can be written as $1/(1 - p_k) f_2(z)$ for some holomorphic function $f_2(z)$ at $p_k$. Similarly, $g(z) = (1 - p_k) g_2(z)$. If we do $f(z) \cdot g(z)$, factors cancel out resulting in a holomorphic function $h(z)$ at $p_k$. Do this for every pole and we conclude $h(z)$ doesn’t have poles and is holomorphic in the entire plane.

We can summarize this as follows:

Corollary 7. Every meromorphic function is the quotient of two entire functions.

Canonical Product and Genus

In the proof of Theorem 6, we showed that by setting $m_n = n$ then

\[\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{m_n + 1} \left(\frac{R}{\abs{a_n}}\right)^{m_n + 1}\]converges and that was enough for $(7)$ to exist. Now suppose we set $m_n$ to a constant $h$ and suppose we can show that

\[(9) \quad \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{h + 1} \left(\frac{R}{\abs{a_n}}\right)^{h + 1}\]converges, which is equivalent to say that:

\[(10) \quad \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{\abs{a_n}^{h + 1}}\]converges (obtained by factoring out the constant $R^{h + 1} / (h + 1)$ from $(9)$). Then we can use a simpler notation if we assume $m_n$ is a constant. Let $E(z)$ be:

\[E_h(w) = \left(1 - w\right) e^{\sum_{k=1}^h w^k/k}\]Then $(7)$ can be written as:

\[f(z) = z^m e^{g(z)} \prod_{n = 1}^\infty E_h\left(\frac{z}{a_n}\right)\]Now let $h$ be the minimum integer for which $(10)$ converges. Then we define $\prod_n E_h(z/a_n)$ as the cannonical product and $h$ the genus of the canonical product. So if $h$ is the genus, we’ve proved that then the canonical product converges. Lemma 8 states the opposite is also true.

Lemma 8. Let $h$ be genus of the canonical product $\prod_n E_h(z/a_n)$. Then $\prod_n E_{h-1}(z/a_n)$ does not converge.

Example

We now cover an example which will be useful in future posts, to find the decomposition of the function $\sin (\pi z)$. We know it has all natural numbers as zeros.

We can first prove that its canonical product has a genus equal to 1 because we know for $h = 0$, $(10)$ becomes:

\[\sum_{n \neq 0} \frac{1}{\abs{n}} = 2 \sum_{n \gt 0} \frac{1}{n}\]and we know the harmonic series does not converge. Conversely, for $h = 1$ we have:

\[\sum_{n \neq 0} \frac{1}{\abs{n}^2} = 2 \sum_{n \gt 0} \frac{1}{n^2}\]which converges to $\pi/6$ [5]. So we have:

\[(11) \quad \sin (\pi z) = z e^{g(z)} \prod_{n \neq 0} \left(1 - \frac{z}{n}\right) e^{z/n}\]To determine $g(z)$ we use the fact that $f’(z)/f(z) = d(\log (f(z)))/dz$. Setting $f(z) = \sin (\pi z)$ we have that $f’(z) = \pi \cos (\pi z)$. Let’s now compute $d(\log (f(z)))/dz$ on the righthand side. We start with the $\log$:

\[\log(f(z)) = \log(z) + g(z) + \sum_{n \neq 0} \log \left(1 - \frac{z}{n}\right) + \frac{z}{n}\]differentiating:

\[\frac{d\log(f(z))}{dz} = \frac{1}{z} + g'(z) + \sum_{n \neq 0} \left(\frac{-1}{n} \frac{1}{1 - \frac{z}{n}} + \frac{1}{n}\right) = \\ \frac{d\log(f(z))}{dz} = \frac{1}{z} + g'(z) + \sum_{n \neq 0} \left(\frac{1}{z - n} + \frac{1}{n}\right)\]Combining everything:

\[\frac{\pi \cos (\pi z)}{\sin (\pi z)} = \frac{1}{z} + g'(z) + \sum_{n \neq 0} \left(\frac{1}{z - n} + \frac{1}{n}\right)\]It’s possible to show that (p. 189 [1]):

\[\frac{\pi \cos (\pi z)}{\sin (\pi z)} = \frac{1}{z} + \sum_{n \neq 0} \left(\frac{1}{z - n} + \frac{1}{n}\right)\]which implies that $g’(z) = 0$ and thus $g(z)$ is constant. To find the value of this constant, we just need one example and we take $z \rightarrow 0$. In that case the terms in the product of $(11)$ tend to 1, so we’re left with:

\[e^{g(z)} = \frac{\sin(\pi z)}{z}\]From Lemma 10 we have:

\[\lim_{z \rightarrow 0} \frac{\sin(\pi z)}{z} = \pi\]So $e^{g(z)} = \pi$. Replacing in $(11)$:

\[\sin (\pi z) = z \pi \prod_{n \neq 0} \left(1 - \frac{z}{n}\right) e^{z/n}\]Which can be simplified further by combining the terms $n$ and $-n$:

\[\sin (\pi z) = z \pi \prod_{n \ge 1} \left(1 - \frac{z^2}{n^2}\right)\]Conclusion

This chapter was one of the most enjoyable to read in a while from Ahlfors. His explanation was relatively easy to follow, except that he didn’t seem mention the result of Lemma 8 explicitly anywhere.

I’ve been wanting to understand the Weierstrass theorem since I studied the Basel problem [5] which makes use of this theorem. The seemingly “random terms” from $(7)$ make a lot more sense when we consider the proof.

Related Posts

Mittag-Leffler’s Theorem . We can think that Weierstrass theorem is for zeros what the Mittag-Leffler’s Theorem is for poles. Recall that the latter say that given a set of complex numbers ${a_n}$ such that $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} a_n = \infty$, we can find a meromorphic function which contains exactly those numbers as poles.

The Basel Problem. In that post, we needed to use the Weierstrass theorem (more precisely the Hadamard factorization theorem) to prove a step that even Euler didn’t provide a proof for and conclude that:

\[\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{n^2} = \frac{\pi}{6}\]Appendix

Lemma 9. Let $z$ be a complex number. Then:

\[\lim_{z \rightarrow 0 }\frac{\log(1 + z)}{z} = 1\]Lemma 10. Let $z$ be a complex number. Then:

\[\lim_{z \rightarrow 0 } \frac{\sin(\pi z)}{z} = \pi\]