kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Circles of Apollonius

Circles of Apollonius

20 Jan 2024

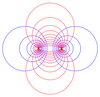

In this post we study the circles of Apollonius or Apollonian circles from a geometric perspective. Later we relate it with concepts from complex analysis.

No prior context is needed for the geometric part. For the Complex Plane section, it’s worth becoming familiar with the series, in particular the Cross-Ratio:

Definition

Let $a$ and $b$ be two points on the plane. The circle of Apollonius induced by $a$ and $b$, is the set of points $p$ such that the distance to $a$ and $b$ has a constant ratio $r$.

More formally, let $d(p, q)$ represent the Euclidean distance between points $p$ and $q$. The circle of Apollonius is the set of $p$ satisfying:

\[(1) \quad \frac{d(P, A)}{d(P, B)} = r\]The points $a$ and $b$ are called the foci.

Circle?

Why is the set of points satisfying $(1)$ called a circle? To begin with we consider the case where $r = 1$. In this case the set $(1)$ is actually a line, perpendicular to the segment $\overline{AB}$ and bisecting it. This is a circle if we assume that a line is a circle with infinite radius.

Henceforth we’ll assume $r \ne 1$. In this case it’s less apparent what geometric object the set $(1)$ defines. Corollary 6 answers that question.

Before that though, we need to build on top of some lemmas and theorems. We start with the angle bisector theorem:

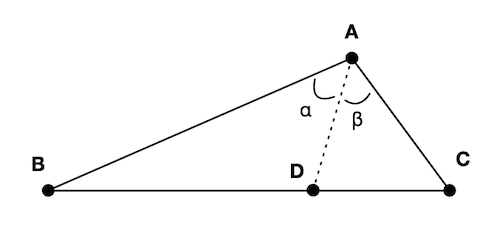

Theorem 1. (Angle bisector theorem) Let $\triangle ABC$ be a triangle and let $D$ be a point on the side ${BC}$ (Figure 1). The segment ${AD}$ bisects (i.e. divides into equal parts) the angle $B\hat{A}C$ if and only if the following holds:

\[\frac{\abs{BD}}{\abs{CD}} = \frac{\abs{AB}}{\abs{AC}}\]

A related theorem is the external angle bisector theorem:

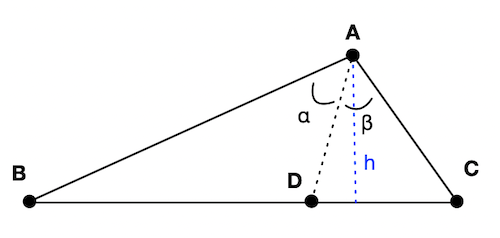

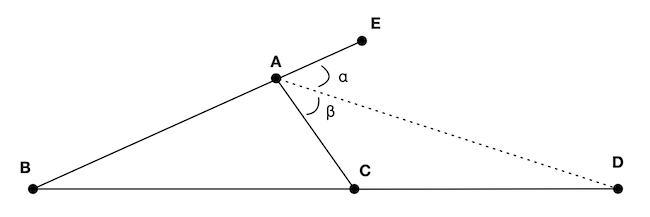

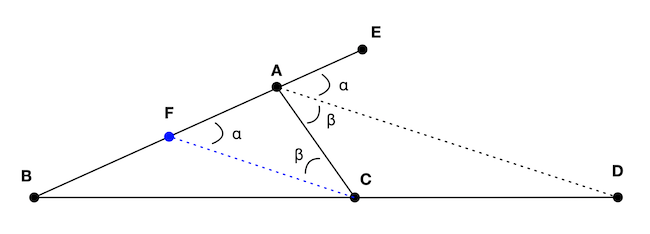

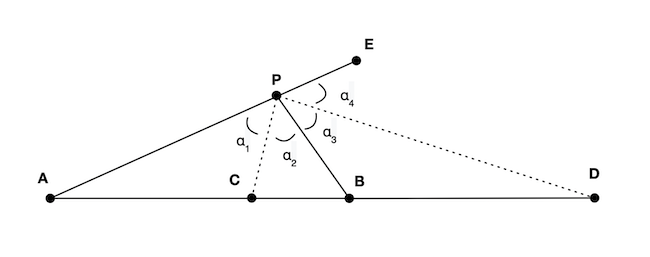

Theorem 2. (External angle bisector theorem) Let $\triangle ABC$ be a triangle and let $D$ be a point on the extended line formed by the points $B$ and $C$, and let $E$ be any point on he extended line formed by the points $A$ and $B$ (Figure 2). The segment ${AD}$ bisects (i.e. divides into equal parts) the external angle of $A$ (i.e. $C\hat{A}E$) if and only if the following holds:

\[\frac{\abs{BD}}{\abs{CD}} = \frac{\abs{AB}}{\abs{AC}}\]

We notice that the triangles $\triangle{BCF}$ and $\triangle{ABD}$ are similar except for a scaling factor. In particular: $$(2.1) \quad \frac{\abs{AB}}{\abs{BF}} = \frac{\abs{BD}}{\abs{BC}} = k$$ So $\abs{AF} = \abs{AB} - \abs{BF} = \abs{BF}(k - 1)$ and $\abs{CD} = \abs{BD} - \abs{BC} = \abs{BC}(k - 1)$. Dividing them: $$(2.2) \quad \frac{\abs{AF}}{\abs{CD}} = \frac{\abs{BF}(k - 1)}{\abs{BC}(k - 1)} = \frac{\abs{BF}}{\abs{BC}}$$ We can rewrite $(2.1)$ as: $$\frac{\abs{AB}}{\abs{BD}} = \frac{\abs{BF}}{\abs{BC}}$$ From $(2.2)$ we have $\abs{BF}/\abs{BC} = \abs{AF}/\abs{CD}$, so we get: $$\frac{\abs{AB}}{\abs{BD}} = \frac{\abs{AF}}{\abs{CD}}$$ Or $$(2.3) \quad \frac{\abs{BD}}{\abs{CD}} = \frac{\abs{AB}}{\abs{AF}}$$ Which is almost what we want, except that we have $\abs{AF}$ instead of $\abs{AC}$, but we haven't used our hypothesis yet.

Now assume that ${AD}$ bisects $C\hat{A}E$, which means $\alpha = \beta$. This implies the triangle $\triangle ACF$ is isosceles with the sides $AF$ and $AC$ being of the same length. So we get $$\frac{\abs{BD}}{\abs{CD}} = \frac{\abs{AB}}{\abs{AF}} = \frac{\abs{AB}}{\abs{AC}}$$ Conversely, suppose that we start with $$\frac{\abs{BD}}{\abs{CD}} = \frac{\abs{AB}}{\abs{AC}}$$ Which together with $(2.3)$ imploes that $\abs{AC} = \abs{AF}$, which by definition means that the triangle $\triangle ACF$ is isosceles and the angles $\alpha = \beta$. QED.

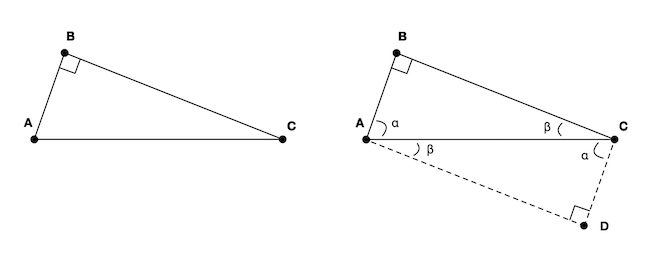

Theorem 3. (Thales Theorem - partial). If $\triangle ABC$ is a rectangle triangle (with $A\hat{B}C = 90^{\circ}$) then point $B$ lies on the circle with the diameter $AC$.

The original Thales Theorem also claims the converse, that if in a triangle $\triangle ABC$, $B$ lies on the circle defined by the diameter $AC$, then $A\hat{B}C = 90^{\circ}$. We don’t need this result here, so we’ll skip the proof.

In order to facilitate calculations in the next Lemma and Theorem, we will make some assumption without loss of generality. First, we assume that $r > 1$. If that’s not the case we swap $A$ and $B$ in $(1)$:

\[\frac{d(P, B)}{d(P, A)} = \frac{1}{r}\]Second, we can perform a translation to the space such that point $A$ is $(1)$ concides with the origin. Third, we can perform a rotation with respect to the origin such that $B$ lies on the positive $x$-axis.

With Lemma 4 we find that the set $(1)$ contains points that allows us to use Theorems 1, 2 and 3:

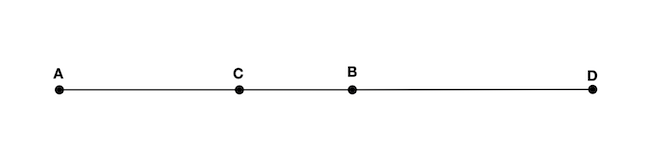

Lemma 4 The set of points satisfying $(1)$ contain points $C$ within the segment $\overline{AB}$ and $D$ external to that segment, as in Figure 3. With

\[(2) \quad \frac{\abs{AC}}{\abs{BC}} = \frac{\abs{AD}}{\abs{BD}} = r\]

Lemma 4 enables us to draw a useful picture to help with Lemma 5. For any point $P$ not in $x$-axis satisfying $(1)$ it will define the triangles and line segments from Figure 4.

Lemma 5. In Figure 4, $\alpha_2 + \alpha_3 = 90^{\circ}$.

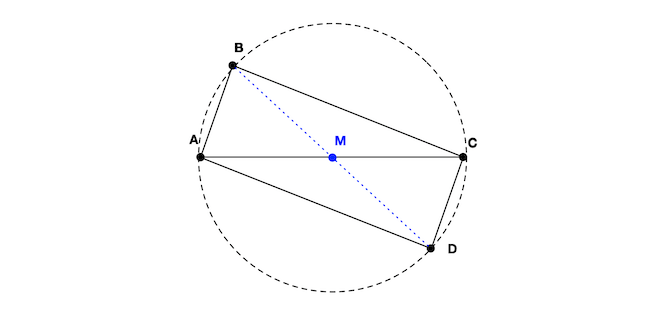

Lemma 5 lets us apply Theorem 3 to conlude that $P$ lies on the circle with diameter $\overline{CD}$. Since we didn’t specify $P$ except that it’s not $C$ or $D$, this leads us to:

Corollary 6. The set of points satisfying $(1)$ defines a circle.

Since $\overline{CD}$ is the diameter, we can find the center $O$ and radius $r$ of the circle:

\[O = \frac{D - C}{2}, \qquad r = \frac{\abs{CD}}{2}\]We can also conclude from $\overline{CD}$ being the diameter that:

Corollary 7. The center of the Apollonious circle induced by $A$ and $B$ is collinear with them.

Complex Plane

The equation $(1)$ can be expressed in terms of complex numbers too. Let $a$ and $b$ be complex numbers and $r$ a real one. Then the set formed by $z$ satisfying:

\[\frac{\abs{z - a}}{\abs{z - b}} = r\]defines a circle in the complex plane. We now connect the circle of Apollonius with concepts from Complex Analysis we studied so far.

Cross Ratio

Recall the cross-ratio for complex points $z_1, z_2, z_3, z_4$ is defined as:

\[(z_1, z_2, z_3, z_4) = \frac{(z_1 - z_3)}{(z_1 - z_4)} \cdot \frac{(z_2 - z_4)}{(z_2 - z_3)}\]If we set $z_1 = A$, $z_2 = B$, $z_3 = P_1$ and $z_4 = P_2$ where $P_1$ and $P_2$ satisfy $(1)$, what do we get?

Theorem 8 The cross-ratio $(A, B, P_1, P_2)$ where

\[\frac{\abs{P_1 - A}}{\abs{P_1 - B}} = \frac{\abs{P_2 - A}}{\abs{P_2 - B}} = r\]Belongs to the unit circle.

References

- [1] Wikipedia - Apollonian circles