kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > The Cardinality of Complex Numbers

The Cardinality of Complex Numbers

16 Sep 2023

The cardinality of a set is the number of elements it contains. For sets with infinitely many elements we can’t define its cardinality using a specific number, but we can compare it with other sets. For example, it can be shown that the set of natural numbers has the same cardinality as the set of rational numbers. These sets are known as countably infinite. On the other hand, the set of real numbers is larger than these.

In this post we’ll explore the cardinality of the set of complex numbers.

Bijection between $\mathbb{R}$ and $\mathbb{C}$

Our main goal is this post is to come up with a bijection between $\mathbb{R}$ and $\mathbb{C}$. This will show that they have the same cardinality!

Because bijection is transitive, if we want to come up with a bijection beween $A$ and $C$, we can instead find bijections between $A$ and $B$ and then between $B$ and $C$. This can help us simplify the problem.

Bijection between $\mathbb{C}$ and $\mathbb{R}^2$

A complex number is composed of two parts: the real and imaginary part. Each part can be any of the real numbers, so we can easily come up with a bijection between the complex numbers and $\mathbb{R}^2$. Now we just need to find a bijection between $\mathbb{R}$ and $\mathbb{R}^2$.

Bijection between $\mathbb{R}$ and $(0, 1)$

Working with $(0, 1)$ i.e. $0 \lt x \lt 1$, $x \in \mathbb{R}$ simplifies things a lot for us, so we can start by finding a bijection between $\mathbb{R}$ and $(0, 1)$.

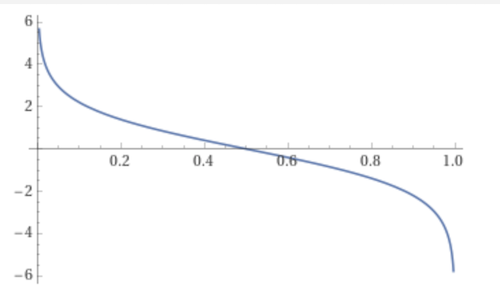

We claim that the pair of functions $\frac{1}{1 + e^{x}}$ and $\ln(\frac{1}{y} - 1)$ form a bijection between $\mathbb{R}$ and $(0, 1)$. For $x \in \mathbb{R}$, we have $0 \lt \frac{1}{1 + e^{x}} \lt 1$ and continuous. For $0 \lt y \lt 1$, when $y$ approaches 1, $\ln(\frac{1}{y} - 1)$ tends to negative infinite and as it approaches 0, it tends to positive infinite. Figure 1 shows the plot for $\ln(\frac{1}{y} - 1)$.

Now our problem is reduced to find the bijection between $(0, 1)$ and $(0,1)^2$.

Bijection between $(0, 1)$ and $(0,1)^2$

The remaining part is to show a bijection between $(0, 1)$ and $(0,1)^2$ exists. We’ll discuss 3 possibilities. These is largely based on MJD’s answer to Examples of bijective map from $\mathbb{R}^3 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ [1].

Strategy 1: Interleaving digits

Consider the pair $(x, y) \in (0, 1)^2$. We want to find a bijection between this pair the scalar $r \in (0, 1)$. We could first try concatenating the digits from one number with the other, for example $r = xy$, but $x$ and $y$ can have an infinite number of digits, so that’s not feasible.

Another strategy we can try is interleaving, or zipping, the digits from each number. For example, for $x = 0.1415…$ and $y = 0.7182…$ we could do $r = 0.17411852…$

It’s convenient that we’re not dealing with negative numbers, because how would we map $-1$ and $2$? It could be mapped to $-12$ but how about $1$ and $-2$ or $-1$ and $-2$?

Non-unique representation

The interleaving of digits doesn’t quite work because the real number representation is not unique! To start, we show that $0.999999…$ equals to $1$.

Proof. To see why, we write $0.999999…$ as the geometric series:

\[9 \left(\frac{1}{10}\right) + 9 \left(\frac{1}{10}\right)^2 + 9 \left(\frac{1}{10}\right)^3 + \cdots\]For geometric series of the form:

\[ar + ar^2 + a^3 + \cdots\]with ratio $r < 1$, we can show it converges to

\[\frac{ar}{1 - r}\]Replacing $a = 9$ and $r = 1/10$, we get

\[\frac{9/10}{1 - 1/10} = 1\]So we have $0.09999… = 1$. QED.

We then claim that the number $0.119999…$ is equal to $0.12$. We write it as $0.11 + 0.009999… = 0.11 + \frac{0.9999…}{100} = 0.11 + \frac{1}{100} = 0.12$.

Now, consider $x = 0.2 = 0.1999…$ and $y = 0.2 = 0.1999…$ which will map to $r = 0.119999…$ and the numbers $x’ = 0.1$ and $y’ = 0.2$ which will map to $r = 0.12$. Since $0.119999 = 0.12$, we have two elements in $\mathbb{R}^2$ mapping to the same element in $\mathbb{R}$, meaning it’s not even an injection and cannot be used to show they’re the same cardinality.

Non-trailing zeroes representation

One workaround for this issue is to only work with the representation of numbers that do not end in zeros. So for $0.1$ and $0.2$ above we would use the representation $0.09999…$ and $0.19999…$ which would map to $0.01999999…$.

This still leave us with a problem: to what pair of numbers does $0.12010101…$ (where $01$ repeats indefinitely) map to? It technically doesn’t end in zeros since it’s periodic but if we “undo” the interleaving we get $0.10000…$ and $0.21111…$. However, since we only work with the non-zero representation, the map in the other direction would be from $0.09999…$ and $0.21111…$ leading to $0.0291919191$ which is definitely not equal to $0.12010101…$ so it’s not a bijection.

Chunking

To work around that problem, we can interleave chunks instead of single digits. Each chunk is formed by leading zeros (possibly none) and one non-zero digit, so for example, $0.0100348…$ is chunked as $0.(01)(003)(4)(8)…$. If we were to interleave this number with say $0.30079001…$, chunked as $0.(3)(007)(9)(001)…$ we’d get $0.(01)(3)(003)(007)(4)(9)(8)(001)…$

Back to the counter-example $0.12010101…$, this now is chunked as $0.(1)(2)(01)(01)…$ so it maps to $0.(1)(01)(01)…$ and $0.(2)(01)(01)…$ avoiding the trailing zeroes issue.

Strategy 2: Schröder-Bernstein Theorem

An alternative to the chunking is to leverage the Schröder-Bernstein Theorem which states that if we have sets $A$ and $B$, and injective functions $f: A \rightarrow B$ and $g: B \rightarrow A$, there exists a bijective function between $A$ and $B$.

From the previous section, we saw that interleaving digits with their non-trailing zeroes representation is an injective function from $(0,1)^2 \rightarrow (0, 1)$ and conversely “unzipping” the digits of a real number $r$ to obtain a pair $(x, y)$ is an injective function from $(0,1) \rightarrow (0, 1)^2$.

So we can use the Schröder-Bernstein theorem to show a bijection exists, even though the theorem is not constructive, so it doesn’t tell us the exactly function.

Strategy 3: Continued fractions

Another approach is to work with irrationals and their continued fractions representation. We’ll need to further reduce the problem, by defining a bijection between reals in $(0,1)$ and the irrationals in $(0,1)$.

Bijection between reals in $(0,1)$ and irrationals in $(0,1)$

The idea is to map real numbers in $(0, 1)$ of the form $\frac{q}{1 + k\sqrt{2}}$, for $q \in \mathbb{Q}$ and $k \in \mathbb{N}$ into $\frac{q}{1 + (k + 1)\sqrt{2}}$ and for other forms to use the identity mapping.

To see why it works we first note that all rational numbers are of the form $\frac{q}{1 + k\sqrt{2}}$ for $k = 0$. We claim that $\frac{q}{1 + (k + 1)\sqrt{2}}$ is irrational: $k + 1$ is a non-zero rational, and dividing, multiplying or adding a rational number with a irrational one is results in an irrational number.

Further, since $0 \lt \frac{q}{1 + k\sqrt{2}} \lt 1$, all rationals in $(0, 1)$ are mapped to irrationals in $(0, 1)$.

Now consider the irrationals of the form $\frac{q}{1 + k\sqrt{2}}$ for $k > 0$. Because we map them to a different irrational $\frac{q}{1 + (k + 1)\sqrt{2}}$, we avoid conflict with the irrationals mapped from the rational numbers as discussed above.

Finally, for all other irrationals we’re using the identity mapping and we are sure they will not conflict with any of the irrationals mapped so far, because otherwise they would be of the form $\frac{q}{1 + k\sqrt{2}}$ and the assumption is that they are not.

We can use similar arguments for the other direction and see this is a valid bijection. This allows us to reduce the problem to finding a bijection between irrationals in $(0,1)$ and irrationals in $(0,1)^2$.

Bijection between irrationals in $(0,1)$ and irrationals in $(0,1)^2$

It can be shown that irrational numbers have a unique continued fraction representation with infinite terms. For example, $\pi$ can be represented by:

\[\pi = 3 + \frac{1}{7 + \frac{1}{15 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{292 + ...}}}}\]or more succinctly by the array $[3; 7, 15, 1, 292, \cdots]$, where all elements are integers and the ones besides the first are positive. Note that the first term is handled in a special way (separated by $;$). But because we’re dealing with the irrationals in $(0,1)$ the first term is always zero, which is convenient.

Now, given two irrational numbers in $(0,1)$ represented by coefficients $[0; a_1, a_2, a_3, …]$ and $[0; b_1, b_2, b_3, …]$ we can map it to another irrational number by interlaving it’s coefficients: $[0; a_1, b_1, a_2, b_2, a_3, b_3, …]$.

We note here why having the range restricted to $(0,1)$ is important: if the first coefficent wasn’t 0, we would have numbers $[a_0; a_1, a_2, a_3, …]$ and $[b_0; b_1, b_2, b_3, …]$ and we’d need to map $a_0$ and $b_0$ somewhere. Alternatively, if we restricted the irrationals to $\mathbb{R}^{+}$, we could guarantee that $a_0, b_0 \ge 0$, and map it to $[a_0; b_0 + 1, a_1, b_1, a_2, b_2, a_3, b_3, …]$.

Conclusion

In school I learned about a bijection between $\mathbb{N}$ and $\mathbb{N}^2$ and also Cantor’s diagonal to show that $\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{R}$, but I don’t recall learning about a bijection between $\mathbb{R}^2$ (or $\mathbb{C}$) and $\mathbb{R}$.

I’ve been reading a book on complex analysis and am trying to make connections between concepts I know and complex numbers.

Related Posts

Topological Equivalence Showing a bijection between sets, reminds me a lot of finding homeomorphisms to demonstrate topological equivalence between topological spaces.

Turing Machines and Undecidability - The idea of chunking using non-zeroes as delimiters vaguely reminds me of the proof of the proposition that determining whether a universal turing machine accepts a string $w$ to be equivalent to the MPCP (Modified Post Correspondence Problem).

Huffman Coding - One way to think about bijection is lossless encoding, like Huffman coding. The strategy of turning a pair $(x, y)$ into a scalar $r$ is a form of encoding, though not for compression purposes.

References

- [1] Mathematics Stack Exchange: Examples of bijective map from $\mathbb{R}^3 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$

- [2] Mathematics Stack Exchange: Is there a bijective map from from $(0, 1)$ to $\mathbb{R}$?

- [3] Mathematics Stack Exchange: Is there a simple, constructive, 1-1 mapping between the reals and the irrationals?