kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Turing Machines and Undecidability

Turing Machines and Undecidability

28 Dec 2013

Jeffrey Ullman is a professor of Computer Science at Stanford. He is famous for his book Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation. He teaches the Automata course in Coursera, and I’ve just finished the most recent edition.

Ullman’s research interests include database theory, data integration, data mining, and education using the information infrastructure. He was Sergey Brin’s PhD advisor and won the Knuth Prize in 2000 [1].

We divide this post in two parts. In the first part, we’ll provide a brief overview of automata theory, including basic concepts and terminology. In Part 2, we’ll focus on the limitations of automatons by discussing undecidability.

Part 1: Automata Theory

In the following sections, we’ll go from the more limited automata, to a push-down automata and then to a turing machine.

Finite automata

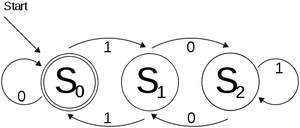

We can think of a finite automaton as a state machine. It’s represented by a directed graph where the nodes represent states and each edge \((u, v)\) connecting two states has a label, which is a symbol from a given alphabet \(\Sigma\). Consider an initial state \(q_0\), a set of final states \(F\) and a string \(w\) of the alphabet \(\Sigma\).

To be more generic, we can describe the edges of the graph as a transition function. It takes as input a state \(p\) and a symbol \(c\) and outputs a new state \(q\). We denote such function as \(\delta\), so we have \(\delta(p, c) \rightarrow q\).

We can then decide if input \(w\) is accepted by this automaton by simulating it on the automaton. That consists in consuming each character \(c\) from \(w\) at a time and moving from one state to another by following the edge labeled \(c\). If there’s no such edge, we can assume it goes to a dead-end state where it gets stuck and is rejected. If after consuming all the input it is in one of the final states, we say it’s accepted, otherwise it’s rejected.

If there’s always at most one edge to take at any point of the simulation, we have a deterministic way to decide wheter \(w\) is accepted, so we call such class of automaton, or DFA for short. In case it has multiple choices, we have a non-deterministic finite automata, or NFA.

Surprisingly, a DFA is as powerful as a NFA, because we can simulate a NFA with a DFA, though such DFA might have an exponential number of states. DFA’s are also as powerful as regular expressions, which is out of the scope of this post.

We define a set of strings as a language. We say that an automaton defines a given language if it accepts all and only the strings contained in this language.

In the case of finite automata, the class of languages that they define is called regular languages.

Push-down automata

A push-down automata is essentially a finite automata equipped with a stack. The symbols that can go into the stack are those from the input and also some additional ones. In this automaton, the transition function takes as input, the state \(p\), the input symbol \(c\) and the element at the top of the stack \(X\). It outputs the new state \(q\) and the new top of the stack that will replace the top \(X\), which can be more than one element or even the empty symbol, meaning that we didn’t put any element on top.

This type of automaton can be shown to be equivalent to a context-free grammar (CFG), which is out of the scope of this post as well, but it’s very common for describing programming languages.

The set of languages for which there is a push-down automata that define them, is called context-free languages, which contains the regular languages.

Turing machines

What could we accomplish with a finite automaton with 2 stacks? Quite a bit. Such automata are called two-push down stack automata. It’s possible to show that a finite automaton with 2 stacks is equivalent to a Turing machine.

So, what is exactly a Turing machine? It’s a device with an state, an infinite tape and a needle that points to a given position on this tape. The input \(w\) is initially written on the tape and the needle points to the first character of \(w\). All the other positions in the tape contains the blank symbol.

The transition function that takes as input the state \(p\) and the input symbol pointed by the needle \(c\) and it outputs the new state \(q\), the new symbol that will be written replacing \(c\) and the direction that the needle moves after that (either right or left). In case there’s no defined transition function for a state and input symbol, we say that the machine halts.

There are two main flavors of TM regarding when an input is considered accepted:

- The TM has a set of final states and whenever we get to one of those states, we accept.

- We accept when the TM halts.

It’s possible to show that in the general case both versions are equivalent, in the sense that both define the same class of languages, which was historically denoted by recursive enumerable languages.

An algorithm for a decision problem is a special type of TM that accepts by final states and it’s always guaranteed to halt (whether or not it accepts). The class of languages that are defined by algorithms are called recursive languages.

Extending Turing machines

We can simulate more general TMs using our the basic TM. For example, we can model a TM with multiple tracks. Instead of having a single element, each position on the tape can contain a tuple, where each element of the such tuple represents the element on each tape with the same position.

We can even have multiple needles, by using a dedicated tape for representing the current position of each additional needle.

Part 2: Undecidability

In this second part of the post we’ll discuss about undecidability. A problem is said undecidable if there’s no algorithm to solve it, that is, no TM that is guaranteed to halt on all its inputs.

The Turing Machine Paradox

Question: Are Turing machines powerful enough so that for any language there exists a corresponding TM that defines it?

Not really. We will next define a language that creates a paradox if a TM exists for it. Before that, we first discuss how we can encode TM’s as strings so it can be used as input to other TM’s.

Encoding Turing machines. Given a description of a Turing machine (the input, the transition functions), it’s possible to encode it as a binary string. Each possible Turing machine will have a distinct binary representation. We can then convert these strings to integer. Since two strings can be converted to the same integer because of leading zeroes (e.g. both 010 and 10 map to 2), we append a 1 before all the strings (e.g. now 1010 maps to 10 and 110 to 6).

We can now order all Turing machines by their corresponding integer representation. Note that some integers might not be encodings of an actual TM, but for simplicity, we can assume it’s a TM that accepts the empty language.

Since a TM can be seen as a string, we can say that a TM accepts itself if it accepts the corresponding encoding of itself as a binary string. We can even define a language as the set of TM encodings that don’t accept themselves:

\[L_d = \{w \mid w \mbox{ is the encoding of a TM that doesn't accept itself} \}\]So we want to know whether there is a TM \(T_d\) for \(L_d\). Suppose there is. Then we ask: does \(T_d\) accepts itself?

The self-referencing property is the origin Russell’s Paradox. It essentially defines a set \(S\) that contains all elements (which can also be sets) that do not contain themselves. The paradox is that if \(S\) contains itself, then there’s a set in \(S\) that do contain itself, which is a contradiction. On the other hand, if it doesn’t contain itself, \(S\) left out a set, which also contradicts the definition of \(S\).

We can use the same analogy for TMs. If \(T_d\) accepts itself, then it is accepting a TM that doesn’t comply with the constraints. If it does not, it left out the encoding of a TM that doesn’t accept itself.

The only assumption we made so far is that there is such TM for language \(L_d\), so we can conclude this was a wrong assumption and thus \(L_d\) is not a recursive enumerable language.

The Universal Turing Machine

Question: Is there an algorithm to tell whether a Turing Machine accepts a given input \(w\)?

To answer this question, we’ll first define a special type of turing machine. The Universal Turing Machine (UTM) is a TM that takes as input a TM \(M\) encoded as string and an input \(w\) as a pair (M, \(w\)) and accepts it if and only if the corresponding TM accepts \(w\). We denote by \(L_u\) the language of the UTM.

We can design the UTM as a TM with 3 tapes (see multiple tapes TM on the Extended Turing Machines section),

- Tape 1 holds the M description

- Tape 2 represents the tape of M

- Tape 3 represents the state of M

The high-level steps we need to carry over (and for which we have to define the proper transition function, but we’re not doing here) are:

- Verify that \(M\) is a valid TM

- Decide how many “bits” of the tape it needs to represent one symbol from \(M\)

- Initialize Tape 2 with input w and Tape 3 with the initial state of \(M\)

- Simulate \(M\), by reading from Tape 1 the possible transitions given the state in Tape 3 and the input at Tape 2.

- If the simulation of \(M\) halts accepting the string w, then the UTM accepts \((M,w)\).

We can now answer the question in the beginning of this section by the following proposition:

Proposition: \(L_u\) is recursive enumerable, but not recursive.

Proof: It’s recursive enumerable by definition, since it’s defined by a TM (in this case the UTM). So we need to show that the UTM is not guaranteed to always halt, that is,.

Suppose there’s such an algorithm. Then we have an algorithm to decide whether a string is in \(L_d\). First we check if \(w\) is a valid encoding of a TM. If it’s not, then we assume it represents a TM that defines an empty language, so obviously it doesn’t accept itself and thus should go into \(L_d\).

Otherwise, we ask our hypothetical algorithm whether it accepts \((w, w)\). If it does, then the TM corresponding to \(w\) accepts itself and should not go into \(L_d\). On the other hand, if our algorithm doesn’t accept, it should go into \(L_d\). We just described an algorithm that defines \(L_d\), but in the previous section we proved that \(L_d\) has no TM that defines it. This contradiction means that our assumption that an algorithm exists for \(L_u\) is incorrect.

This is equivalent to the halting problem, in which we want to know whether a program (a Turing machine) will halt for a given input or run forever.

Post Correspondence Problem

Question: What are other problems undecidable problems?

We can show a problem is undecidable by reducing an already known undecidable problem to it. In particular, if we can show a particular problem can be used to simulate an universal Turing machine, we automatically prove it undecidable. We’ll now do this with a fairly simple problem to describe and that has no apparent connection to turing machines.

The post correspondence problem (PCP) can be stated as follows. Given \(n\) pairs of strings of the form \((a_i, b_i)\), \(1 \le i \le n\), the problem consists in finding a list of indexes \(R = \{r_1, r_2, \cdots, r_k\}\) such that concatenating the pairs in this order leads to the same string, that is, \(a_{r_1}a_{r_2} \cdots a_{r_k} = b_{r_1}b_{r_2} \cdots b_{r_k}\) (note that an index can be used more than once in the solution).

There’s a stricter version of this problem in which the first pair of the input must be the first pair in the solution, which we’ll refer to MPCP. This doesn’t make the problem harder because it’s possible to reduce it to the original PCP.

It’s possible to simulate a TM by solving the MPCP so that there’s a solution to the MPCP if, and only if, the TM accepts an input \(w\). We provide the detailed reduction in the Appendix for the interested reader. This means that the if there exist an algorithm for PCP (and thus for MPCP), we have an algorithm for any TM, including the UTM, which is a contradiction, and thus we conclude that PCP is undecidable.

Many other problems can be proved to be undecidable by reducing the PCP to them. The list includes some decision problems regarding Context Free Grammars. For example, given a CFG, tell whether a string can be generated in more than one way (whether a CFG is ambiguous); or whether a CFG generates all the strings over the input alphabet; or whether a CFL is regular;

Conclusion

So far this is the second course I finish on coursera (the other one I did was the Probabilistic Graphical Models). I’m very glad that classes from top tier universities are freely available on the web.

Automata theory was one of the gaps in my computer science theory base, especially Turing machines. I’ve done an introductory course on theoretical computer science, but it was mostly focused on intractable problems and cryptography.

References

- [1] Wikipedia - Jeffrey Ullman

- [2] Slides from Automata Course - Coursera

Appendix

Proposition. It’s possible to decide whether an universal turing machine accepts a string by reducing it to MPCP.

Sketch of proof. We won’t give a formal proof of the reduction, but the idea is pretty neat and after understanding it, the reduction becomes more intuitive.

First thing, let’s define a snapshot from a simulation of a TM. A snapshot is a compact description of the TM in a particular simulation step. We can represent it by placing the needle to the left of the tape position it points to. We can omit both the right and left infinite endpoints that are composed eintirely by blanks.

Thus, the first snapshot is represented by \(q_0 w_1\cdots w_n\). If we move the needle to the right writing \(X\) to the current position and changing the state to \(p\), the snapshot becomes \(x p w_2 \cdots w_n\). If instead from the first snapshot we moved to the left, writing \(X\) and changing the state to \(p\), we would have \(p \square x w_2 \cdots w_n\), where \(\square\) is the blank symbol and we need to represent it because it’s not part of the contiguous infinite blanks block anymore.

And each incomplete solution of the MPCP, we have the first part one step behind the second part. With that, we can “tie” to snapshots together by a pair, which can be use to encode the transition function.

The instance we’ll build for the MPCP will consist of the following classes of pairs:

First pair, represent the initial snapshot:

(1) \((\hash , \hash q_0w\hash )\)

Delimiter pair, to separate adjacent snapshots:

(2) \((\hash , \hash )\)

Copy pair, to copy tape symbols that are not involved in the transition function. For each tape symbol \(X\) we create the pair

(3) \((X, X)\)

Transition function pairs

For a move to the right, that is, for each \(\delta(q, X) \rightarrow (p, Y, R)\) we create the pair

(4) \((qX, Yp)\)

For a move to the left, that is, for each \(\delta(q, X) \rightarrow (p, Y, R)\) we create the pair

(5) \((ZqX, pZY)\)

In case \(X\) is the blank character, the right movement, that is \(\delta(q, B) \rightarrow (p, Y, R)\) will become:

(6) we create \((q\hash , Yp\hash )\)

The left movement, that is \(\delta(q, B) \rightarrow (p, Y, L)\) will become:

(7) \((Zq\hash , pZY\hash )\)

Final state pairs

For a final state \(f\) and for all tape symbols \(X, Y\) we add the following auxiliary pairs, from (8) to (10):

(8) \((XfY, f)\)

(9) \((fY, f)\)

(10) \((Xf, f)\)

(11) \((f\hash \hash , \hash )\)

Simulation - Example

The solution will have to start with pair (1), because it’s the first pair and we’re solving the MPCP.

\(\hash\) \(\hash q_0 w_1 \cdots w_n\)

We can now simulate a movement. For example, say we have a right move defined by \(\delta(q_0, w_1) \rightarrow (p, x, R)\) by applying the corresponding pair (4) \((q_0 w_1, x p)\), which will lead us to the partial solution

\(\hash q_0 w_1\) \(\hash q_0 w_1 \cdots w_n \hash x p\)

for now, we can only use the pairs (3), because we need to match \(w_2, w_3, \cdots w_n\), so we apply those pairs until we get

\(\hash q_0 w_1 \cdots w_n\) \(\hash q_0 w_1 \cdots w_n \hash x p w_2 \cdots w_n\)

Now, the only pair that can follow is (30, that is, \((\hash , \hash )\), which will finish the snapshot:

\(\hash q_0 w_1 \cdots w_n \hash\) \(\hash q_0 w_1 \cdots w_n \hash x p w_2 \cdots w_n \hash\)

Note that the pairs of form (3) are only used to copy the remaining part of the tape. That’s because the transition function itself is local, in the sense that it doesn’t know about the tape values that are not involved its definition.

This movement is analogous for the other transition functions.

The remaining case is when the reach a final state, in which we want to accept my making the first part of the partial solution to catch up with the second part.

Say we are in this stage:

\(\cdots \hash\) \(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash\)

where \(f\) is a final stage. We first apply the copy pair (3) on A:

\(\cdots \hash A\) \(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash A\)

and then use pair (8) as \((BfC, f)\) to get

\(\cdots \hash ABfC\) \(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash Af\)

we can only copy and finish the snapshot using (3) and (4):

\(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash\) \(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash\)

we need the pair (8) again, now as \((AfD, f)\) to get

\(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfD\) \(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash f\)

again, by copying and finishing the snapshot we have,

\(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash\) \(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash fE\hash\)

now we use the pair (9) as \((fE, f)\) to obtain

\(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash fE\) \(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash fE\hash f\)

ending another snapshot

\(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash fE\hash\) \(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash fE\hash f\hash\)

finally we use the closing pair (11)

\(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash fE\hash f\hash \hash\) \(\cdots \hash ABfCDE\hash AfDE\hash fE\hash f\hash \hash\)

Note that the final closing is carried over using several auxiliary snapshots that don’t actually correspond to the actual simulation, but it’s easy to obtain the right snapshots from a solution to the MPCP.