kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > DNA Assembly

DNA Assembly

22 Jan 2019

In this post we’ll discuss the problem of reconstructing a DNA segment from its fragments, also known as DNA assembly.

Context. When we first talked about DNA sequencing, we learned that there’s no good way to “scan” the whole series of nucleotides from a DNA with current technology. What can be done is to break the target segment into many small (overlapping) segments and then rely on computers to help with the task of reconstructing the original DNA sequence from these segments.

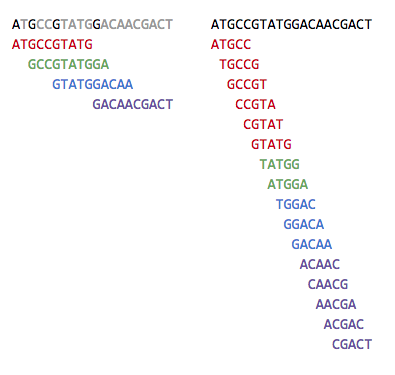

We can start by making some assumptions over the nature of the fragments to start. First, we’ll assume every fragment has the same length and second that we have every possible fragment of such length.

For instance, if our sequence is TATGGGGTGC, all possible fragments of length 3 are: ATG, GGG, GGG, GGT, GTG, TAT, TGC, TGG.

Note that the fragments overlap with each other. For example, TAT and ATG have an overlap of AT. This is crucial for us solve the problem, since if there was no overlap it would be impossible to order the fragments to obtain the original sequence, since there would be no “link” between any two fragments.

Let’s state the problem more formally given these constraints.

The String Reconstruction Problem

Definitions. A k-mer of a string S is any substring of S with length k. The String Composition Problem consists in, given the set of all k-mers from S, reconstruct the string S.

Reusing the example from above, if we are given ATG, GGG, GGG, GGT, GTG, TAT, TGC, TGG, we could reconstruct the string TATGGGGTGC. We’ll now see a way to solve this problem.

Solution. Assuming a solution exists, it will consist of a (ordered) sequence of the k-mers such that adjacent k-mers overlap in k-1 positions. From the example above, the permutation is

TAT, ATG, TGG, GGG, GGG, GGT, GTG, TGC

And two adjacent k-mers such as TGG and GGG, overlap in k-1 positions (GG).

We can model this problem as a graph problem. If we define a directed graph where each vertex corresponds to a k-mer, and an edge (u, v) exists if and only if the suffix of k-mer u is the prefix of the k-mer v, in other words, u overlaps with v.

Now, if we can find a path visiting each vertex exactly once, that will be a valid reconstructed string. This is known as the Hamiltonian path problem for general graphs it’s a NP-Hard problem.

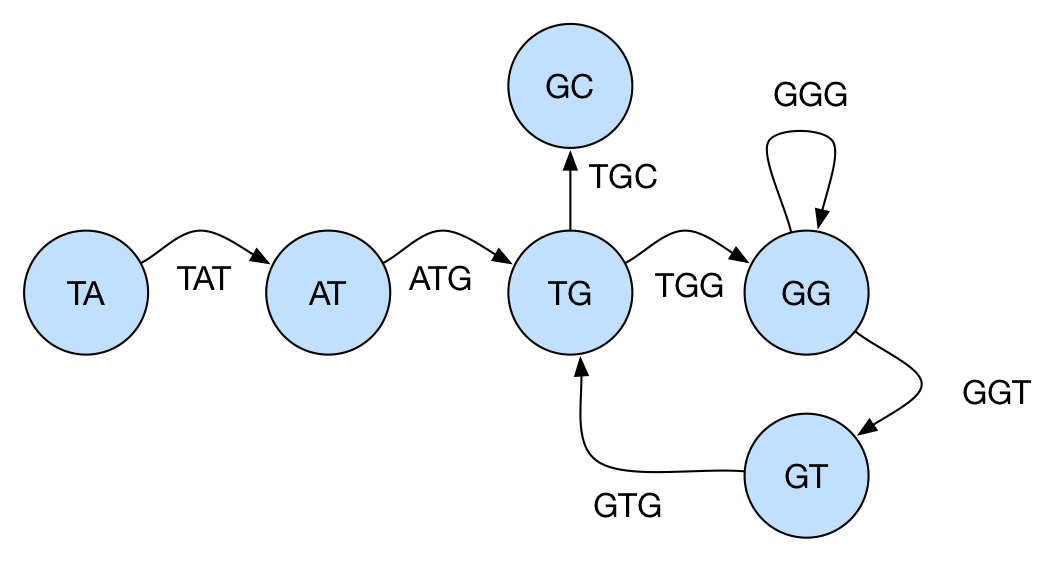

Instead, we can model this problem using a graph as follows: for each k-mer, we have a vertex corresponding to its prefix of length k-1 and another to its suffix with length k-1. For example, for a k-mer TGG, there would exist vertices TG and GG. There’s then an edge from u to v, if the overlap of u and v in k-2 positions is a k-mer in the input. In the example, above, there’s an edge from TG to GG because TGG is a k-mer. Note we can have repeated (multiple) edges.

In this new graph, if we can find a path visiting each edge exactly once, we’ll find a reconstructed string to the set of k-mers. To see why, we can observe that each edge in this new graph is a k-mer and two consecutive edges must overlap in k-1 positions (the overlap being the vertex that “links” these two edges). The graph for the example we discussed above can be seen below:

Note that this second graph is the line graph of the one we first used, in a similar fashion that a de Bruijn graph of dimension n is a line graph of the one with dimension n-1. In fact, these graphs are a subgraph of the de Bruijn graphs.

As we saw in our discussions about Eulerian Circuits that this is a much easier problem to solve.

Dealing with Ambiguity

Even if are able to solve the String Reconstruction problem, we might not end up with the right DNA segment. In [1], the authors provide the example TATGCCATGGGATGTT which has the same 3-mer composition of TAATGGGATGCCATGTT. Let’s see strategies employed to work around this problem.

The String Reconstruction from Read-Pairs Problem

While it’s currently infeasible to generate longer fragments that would reduce ambiguity, it’s possible to obtain what is called read-pairs. These are a pair of k-mers that are separated by a distance of exactly d in the target segment.

For example, TGC and ATG are a pair of 3-mers separated by distance 1 in TATGCCATGGGATGTT. We refer to a pair of k-mers separated by distance d as (k, d)-mers, or (pattern1 | pattern2) if we can omit the distance.

Solution. We can construct a de Bruijn-like graph for this problem too, which we’ll call Paired de Bruijn graph. First, let’s define the prefix and suffix of a (k, d)-mer. Given a (k, d)-mer in the form of (a1, ..., ak | b1, ..., bk), its prefix is given by (a1, ..., ak-1 | b1, ..., bk-1) and its suffix by (a2, ..., ak | b2, ..., bk).

For every (k, d)-mer, we’ll have one vertex corresponding to the prefix and one to the suffix of this (k, d)-mer. There’s an edge from vertex u to vertex v if there’s a (k, d)-mer whose prefix is u and suffix is v.

Similar to the solution to the String Reconstruction problem, we can find an Eulerian path, but in this case that might not yield a valid solution. In [1] the authors provide an example:

Consider the set of (2, 1)-mers is given by (AG|AG), (AG | TG), (CA | CT), (CT | CA), (CT | CT), (GC | GC), (GC | GC), (GC | GC), (TG | TG).

After constructing the graph, one of the possible Eulerian paths is (AG|AG) → (GC | GC) → (CA | CT) → (AG | TG) → (GC | GC) → (CT | CT) → (TG | TG) → (GC | GC) → (CT | CA) which spells AGCAAGCTGCTGCA, which is a valid solution.

However, another valid Eulerian path, (AG|AG) → (GC | GC) → (CT | CT) → (TG | TG) → (GC | GC) → (CA | CT) → (AG | TG) → (GC | GC) → (CT | CA) does not yield a valid string.

In [1] the authors don’t provide an explicit way to overcome this issue but they go on to describe how to enumerate all Eulerian paths, which seems to suggest a brute-force approach.

Practical Challenges

Missing fragments. One of the assumptions we made, that all fragments of the sequence are present doesn’t hold true for the state-of-the-art sequencers.

A technique to address this issue is to break the fragments into smaller ones until we get full coverage.

This trades off coverage with ambiguity, since smaller k-mers are more likely to contain repeats and that might not lead to a single solution.

Typos. Another limitation of sequencers is that they can misread nucleotides. If we perform multiple reads - some containing the correct nucleotides, some not - we’ll end up with a graph where some paths are valid and some are not. It’s possible to remove them via heuristics but they’re not perfect and can lead to the removal of valid paths.

Conclusion

While following the textbook [1] I felt a bit lost due to so many detours and kept losing track of the main problem being solved. Because the textbook is meant to also be accessible to people without prior knowledge of Computer Science, so it does need to provide the base for concepts such as Graph Theory.

One think I missed from the content were a section for experiment results. Bioinformatics is a highly applied branch of Computer Science and all of these methods are heuristics or based on approximate models. I’d be interested in knowing how well they perform in practice.

What I liked the most about the presentation style is that it provides a simpler solution first, describe the issues with it and then provide a better solution. This helps understanding on why a given algorithm is this or that way.

Reconstructing a string using (k,d)-mers in an efficient way seems like an open problem, given the solution presented requires brute force in the worst case. I wonder if there has been any progress since.

References

- [1] Bioinformatics Algorithms: An Active Learning Approach – Compeau, P. and Pevzner P.

- [2] Wikipedia - Sequence Assembly