kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > DNA Sequencing

DNA Sequencing

04 Sep 2018

Frederick Sanger was a British biochemist. He is known for the first sequencing of a protein (1955) and a method for sequencing DNA that bears his name, the Sanger Method. Sanger won two Nobel Prizes in Chemistry [1].

In this post we’ll talk about one of the first steps of DNA analysis, DNA sequencing, which is obtaining the data from the DNA, how it’s performed (we’ll focus on the Sanger method) and some interesting computational problems associated with it.

This is the second post in the series of Biochemistry studies from a Computer Scientist perspective. Our first post is a brief discussion of basic concepts in Cell Biology.

DNA Sequencing

DNA sequencing is the determination of the physical order of the nucleotide bases in a molecule of DNA.

The first living organism to have its genome sequenced was a bacteria, Haemophilus influenzae, whose genome is about 1.8 million base pairs.

Genome represents the whole set of genetic information of an organism. For a bacteria, it’s singular circular chromosome, but for humans it’s the set of all 23 pairs of chromosomes. A base-pair(shortened as bp) refers to a pair of nucleotides (bases) that are bound together in the double-strands of DNA.

In the human genome, there are 3 billion of base-pairs, and it took 13 years for it to be completed.

There are two main methods of sequencing, Sanger and Next-generation [5]. We’ll talk about the Sanger in details and discuss briefly the Next-generation from a real-world use case.

Sanger Sequencing

The Sanger method is able to determine the nucleotide sequence of small fragments (up to abound 900bps) [5] of DNA.

Overview

The first step is cloning the fragment into multiple copies (like billions) by a process called amplification. This is essentially mimicking the DNA cloning process in an artificial setup. In very high level we have:

- Separate the double strands (denaturation)

- Add a special molecule (primer) to the extremity of each strand

- Extend the primer with nucleotides until it reaches the other extremity Once this is complete, we end up with two double-stranded fragments. We can repeat the process to generate many copies of the original fragment (theoretically doubling at each step). This process is known as Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

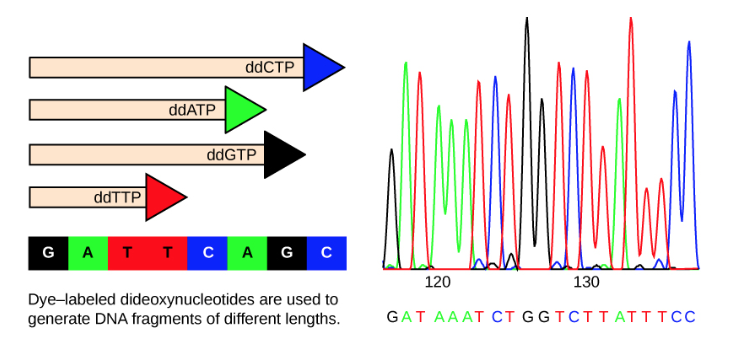

Once we have enough copies of the fragment, we do a similar process, but this time, we also allow extending the primer with a special nucleotide named (dideoxy nucleotide). The key difference is that once it’s added, a dideoxy nucleotide cannot be further extended, and it also contains a special marker that causes each different base to have a different color. The process is now the following:

- Separate the double strands (denaturation)

- Add a special molecule (primer) to the extremity of each strand

- Add to the primer either

- Regular nucleotide (non-terminal - can be further extended)

- Dideoxy nucleotide (terminal - cannot be further extended) Now, instead of ending up with more clones, we’ll have fragments with a variety of lengths.

We then run theses fragments through a process called Capillary Gel Electrophoresis which roughly consists in subjecting the fragments to a electric field, which then causes fragments to move with speed proportional to their length (the smaller the fragment the faster it moves). Once a group of fragments (which have the same length) reach a sensor at end of the field, we make use of the color marker in the special nucleotide at the tip of the fragment to determine the base of that dideoxy nucleotide. This enables us to determine the sequence of the nucleotides in the original fragment!

To given an example, say that the original sequence is GATTCAGC. Because there are many copies of the fragment after amplification, it’s very likely that we’ll end up with fragments with all possible lengths, from 1 to 8. Since a fragment of length 1 moves faster than any other, it will reach the sensor first. We know that a fragment with length 1 is a base pair G-C, and C is a dideoxy nucleotide (if it was not, it would have continued extended further). Say the color marker for C is orange. Then the first color to be captured by the sensor will beorange. The second set of fragments to reach the sensor is of length 2, which is a fragment (G-C, A-T), where T is a dideoxy nucleotide. If we assume it has color red, that’s the color which will be captured next by the sensor. You can see that based on the colors captured by the sensor we can infer the nucleotide sequence in the original segment.

Details

Let’s go in more details for these processes. For both cases we work with solutions. Finer grained manipulation of molecules is infeasible.

To separate the double strands we heat the solution up to 96ºC, in a process we call denaturation. The high temperature causes the hydrogen bonds between pairs of nucleotides to break.

In the same solution we have the primer molecules (aka oligonucleotides) which are carefully chosen to match the beginning of the DNA strand. They also bind to DNA at a higher temperature than the strands (e.g. 55ºC). This is important because we can now lower the temperature of the solution slowly, enough so that primers can bind, but not so low to the point where the original strands will join back together. This slow cooling is called annealing. These primers can be synthesized artificially.

Gap in understanding: how to choose the right primer, since we need to know at least some of sequence from the nucleotide in order to know which primer will end up binding there? One possible explanation is that we know the exact sequence where a DNA was cut if we restriction enzymes, since their binding site is known [9] and hence we have an idea of the result endpoints after the cut.

We also add an enzyme, DNA polymerase, and nucleotides to the solution. The enzyme is able to extend the original primer segment by binding free nucleotides in the solution. In particular we use the enzyme of a bacteria that lives at 70ºC (Thermus Acquaticus), also know as Taq polymerase because it is functional at higher temperatures. Performing the replication at a higher temperature prevents the separated strands from gluing together again.

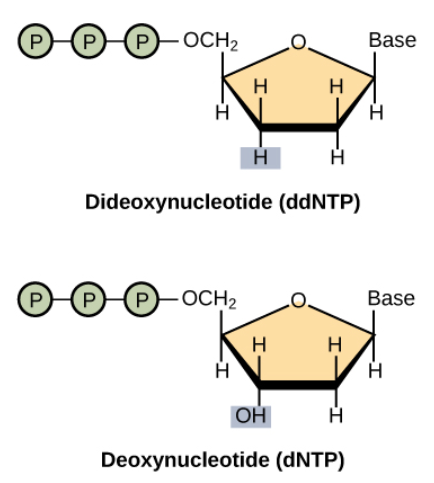

The dideoxy nucleotide are modified versions of the regular nucleotide by supressing the OH group. They can still be incorporated to the primer via the DNA polymerase, but they prevent other nucleotides to binding to them via the sugar-phosphate binding.

In addition these dideoxy nucleotides contain a fluorescent molecule whose color is unique for each different type of base. How are these molecules “inserted” into the nucleotides? The abstract of [6] states:

Avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase is used in a modified dideoxy DNA sequencing protocol to produce a complete set of fluorescence-tagged fragments in one reaction mixture. which suggests it’s possible to synthesize them by using a specific virus.

Next-Generation Sequencing (Illumina)

The Sanger method is a very slow process, making it infeasible for analyzing large amounts of DNAs such as the human genome.

Modern sequencers make use of the “Next-generation” methods, which consist in massive parallelism to speed up the process. The most advanced sequencer in the market is produced by a company called Illumina. As of the time of this writing, their top equipment, Hiseq X Ten, costs about $10 million dollars, can sequence about 18k full genomes a year and it costs about $1000 per genome [2, 3].

Illumina’s educational video [4], describes the process:

- Cut a long sequence into small fragments

- Augment segments with metadata (indices) and adapters

- Have the segments attach to beads in a glass plate via the adapters. The beads are basically the primers.

- Amplify the segments (massive cloning)

- Extend the primer with fluorescent nucleotides

- Every time a nucleotide is added, it emits light which is captured by a sensor After the process is over, we have the sequence of many fragments based on the colors that were emitted.

We can see that the principles resemble the Sanger method, but it uses different technologies to allow a very automated and parallel procedure.

This whole process is very vague and it’s hard to have a good understanding of it. It’s understandable given that a lot of the information is likely industry secret.

Sequencing vs Genotyping in personal genomics

Some of the most popular personal genetic analysis companies, such as 23andMe, provide a service in which they analyze the user DNA for a small fee. It’s way cheaper than the full genome analysis provided by Illumina, but that’s because these companies don’t do DNA sequencing, but rather genotyping.

Genotyping is the process of determining which genetic variants an individual possesses. This is easier than sequencing because a lot of known diseases and traits can be traced back to specific regions and specific chromosomes.

This is the information you most likely want to know about yourself. Remember that the majority of DNA in complex organisms is not useful (introns). In humans genome, exome (the part of DNA consisting of exons) account for less than 2% of total DNA.

Sequencing technology has not yet progressed to the point where it is feasible to sequence an entire person’s genome quickly and cheaply enough to keep costs down for consumers. It took the Human Genome Project, a consortium of multiple research labs, over 10 years to sequence the whole genomes of just a few individuals.

Sequence Assembly Problem

Current technology is unable to sequence large segments of DNA, so it has to break it down into small fragments. Once that is done, we need to reconstruct the original sequence from the data of individual fragments.

There are two scenarios:

- Mapping: matching fragments of DNA to existing sequences by some similarity criteria

- De-novo: reconstruct the DNA when there’s no prior data about that sequence. There is a family of computational methods for the mapping case known as Sequence Assembly, which we’ll study in more details in a future post.

Gap in understanding: It’s unclear what exact information is expected for the De-novo sequencing. It is impossible to determine the original sequence by only having data about individual segments, in the same way it’s impossible to reconstruct a book by only knowing it’s paragraphs contents (but not their order), borrowing the analogy from Wikipedia [8].

One thing I can think of is that if we repeat the experiments multiple times, each time cutting the molecules at different places, it might be possible to infer the relative order of the segments if they’re unique enough.

For example, if the original segment is: GATTCAGC and we run two experiments, one yielding (GAT, TCAGC) and another (GATTC, AGC), then in this case there’s only one way to assemble (order) these sequences in a consistent way.

Conclusion

In this post we studied some aspects of DNA sequencing. I found the Sanger method fascinating. In Computer Science ideas usually translate to algorithms and code very directly, but in other science branches the mapping from ideas to implementation is a problem in itself.

In Mechanics for example, we have to work with the physical world, so when converting from a circular movement to a linear one requires some clever tricks.

This needs to be taken to another level in Molecular Biology, because we don’t have direct access to the medium like we do in a mechanical device, for example, we can’t directly manipulate a double strand of DNA fragment to separate it, but have to resort to indirect ways.

The field of Biotechnology seems to be progressing at such a pace that it was challenging to find good sources of information. I’m yet to find a resource that explains end to end the steps from the process that takes a sample of cells and outputs the DNA nucleotides to a computer, including the technical challenges in doing so. This is what this post aimed to do.

References

- [1] Wikipedia - Frederick Sanger

- [2] Genohub - Illumina’s Latest Release: HiSeq 3000, 4000, NextSeq 550 and HiSeq X5

- [3] Illumina Hiseq-X

- [4] Youtube - Illumina Sequencing by Synthesis

- [5] Khan Academy - DNA sequencing

- [6] Science Magazine: A system for rapid DNA sequencing with fluorescent chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides

- [7] Towards Data Science - DNA Sequence Data Analysis - Starting off in Bioinformatics

- [8] Wikipedia - Sequence assembly

- [9] Dummies - How Scientists Cut DNA with Restriction Enzymes