kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Eulerian Circuits

Eulerian Circuits

26 Nov 2018

Leonhard Euler was a Swiss mathematician in the 18th century. His paper on a problem known as the Seven Bridges of Königsberg is regarded as the first in the history in Graph Theory.

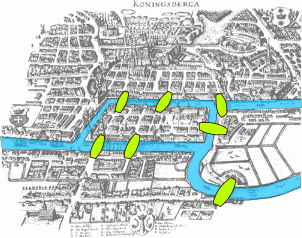

The history goes that in the city of Königsberg, in Prussia, there were seven bridges connecting different mass of lands along the Pregel river (see Figure 1). The challenge was to find a path through the city that crossed the bridges exactly once. Euler showed that no such solution existed.

Interesting unrelated fact: Today Königsberg called Kaliningrad in Russia, and Kaliningrad is actually separated from Russia geographically, lying between Lithuania and Poland.

Figure 1: Map of Königsberg and the seven bridges. Source: Wikipedia

The solution to the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem eventually led to a branch of Mathematics known as Graph Theory. In this post we’ll be talking about the theoretical framework that can be used to solve problems like the Seven Bridges of Königsberg, which is known as Eulerian Circuits.

We’ll provide a general definition to the problem, discuss a solution and implementation, and finally present some extensions and variations to the problem.

Definition

Let $G(V, E)$ be a connected undirected graph, where $V$ is the set of vertices and $E$ the set of directed edges, and where $(v, w)$ denotes an edge between vertices $v$ and $w$. The Eulerian circuit problem consists in finding a circuit that traverses every edge of this graph exactly once or deciding no such circuit exists.

An Eulerian graph is a graph for which an Eulerian circuit exists.

Solution

We’ll first focus on the problem of deciding whether a connected graph has an Eulerian circuit. We claim that an Eulerian circuit exists if and only if every vertex in the graph has an even number of edges.

We can see this is a necessary condition. Let $v$ be a node with an odd number of edges. Any circuit traversing all edges will have to traverse $v$. Moreover, it will have to use one edge to “enter” $v$ and one edge to “leave” $v$. Since this circuit can traverse each edge no more than one time, it will have to use different edges each time, meaning it needs 2 edges every time it crosses $v$. If there are an odd number of edges, one edge will be left unvisited.

To show this is sufficient, we can provide an algorithm that always finds an Eulerian circuit in a graph satisfying these conditions. Start from any vertex $v$ and keep traversing edges, deleting them from the graph afterwards. We can’t get stuck on any vertex besides $v$, because whenever we enter an edge there must be an exit edge since every node has an even number of edges. Thus eventually we’ll come back to $v$, and this path form a circuit.

This circuit doesn’t necessarily cover all the edges in the graph though, nor it means that are other circuits starting from $v$ in the remaining graph. It must be however, that some node $w$ in the circuit we just found has another circuit starting from it. We can repeat the search for every such node and we’ll always find another sub-circuit (this is a recursive procedure, and we might find sub-sub-circuits). Note that after we remove the edges from a circuit, the resulting graph might be disconnected, but each individual component is still Eulerian.

Once we have all the circuits, we can assemble them into a single circuit by starting the circuit from $v$. When we encounter a node $w$ that has a sub-circuit, we take a “detour” though that sub-circuit which will lead us back to $w$, and we can continue on the main circuit.

Implementation

We’ll use the algorithm first described by Hierholzer to efficiently solve the Eulerian circuit problem, based on the proof sketched in the previous session.

The basic idea is that given a graph and a starting vertex $v$, we traverse edges until we find a circuit. As we’re traversing the edges, we delete them from the graph.

Once we have the circuit, we traverse it once more to look for any vertices that still have edges, which means these vertices will have sub-circuits. For each of these vertices we merge the sub-circuit into the main one. Assume the main circuit is given by a list of vertices \((v, p_2, ... , p_k-1, w, p_k+1, ..., p_n-1, v)\) and $w$ is a vertex with a sub-circuit. Let \((w, q_1, ..., q_m-1, w)\) be the sub-circuit starting from $w$. We can construct a new circuit \((v, p_2, ..., p_k-1, w, q_1, ..., q_m-1, w, p_k+1, ..., p_n-1, v)\).

Let’s look at a specific implementation using JavaScript (with Flow). The core of the algorithm implements the ideas discussed above:

function find_circuit(graph: Graph, initialVertex: number) {

let vertex = initialVertex;

const path = new Path();

path.append(vertex);

while (true) {

const edge = graph.getNextEdgeForVertex(vertex);

if (edge == null) {

throw new Error("This graph is not Eulerian");

}

const nextVertex = edge.getTheOtherVertex(vertex);

graph.deleteEdge(edge);

vertex = nextVertex;

path.append(vertex);

// Circuit found

if (nextVertex === initialVertex) {

break;

}

}

// Search for sub-circuits

for (vertex of path.getContentAsArray()) {

// Since the vertex was added, its edges could have been removed

if (graph.getDegree(vertex) === 0) {

continue;

}

let subPath = find_circuit(graph, vertex);

// Merge sub-path into path

path.insertAtVertex(vertex, subPath);

}

return path;

}The complete code is on Github.

Analysis

We’ll now demonstrate that the algorithm described above runs in linear time of the size of the edges (i.e. $O(\abs{E})$).

Note that find_circuit() is a recursive function, but we claim that the number of times the while() loop executes across all function calls is bounded by the number of edges. The key is in the function:

graph.getNextEdgeForVertex(vertex);graph is a convenience abstraction to an adjacency list, where for each vertex we keep a pointer to the last edge visited. Because of this getNextEdgeForVertex() will visit each edge of the graph at most once and we never “go back”. Since the graph object is shared across all function calls (global), we can see that the number of calls to getNextEdgeForVertex() is bounded by $O(\abs{E})$, so is the number of times all while() loops execute.

Now we just need to prove that every other operation in the while() loop is $O(1)$. The only non-obvious one is:

graph.deleteEdge(edge);This is a lazy deletion, meaning that we just set a flag in edge saying it’s deleted and it will later be taken into account by callers like graph.getNextEdgeForVertex() and graph.getDegree(). Hence, this is an $O(1)$ operation.

For getNextEdgeForVertex(), we must skip edges that have been deleted, so we might need to iterate over a few edges before we find an undeleted one (or none if the graph is not Eulerian - in which case we terminate the algorithm). Since we’re still always processing at least one edge in every call to getNextEdgeForVertex() the argument about the total calls being bounded by $O(\abs{E})$ holds.

In order for getDegree() to be an $O(1)$ operation, we need to keep a non-lazy count of the degree of a vertex, but we can do it in $O(1)$ when deleting an edge.

Finally, let’s analyze the second loop. The number of iterations is proportional to the length of the circuit. Since every possible circuit found (including the ones found recursively) are disjoint, the total number of times we loop over the vertices from circuits (across all function calls) is also bounded by the number of edges.

We already saw getDegree() is $O(1)$ even with lazy deletion. The remaining operation is

path.insertAtVertex(vertex, subPath);if we store the paths as a linked list of vertices, inserting subPath at a given node can be done in $O(1)$ if we keep a reference from each vertex to its last (any actually) occurrence in the path.

Directed Graphs

We can extend the definition of Eulerian graphs to directed graphs. Let G(V, A) be a strongly connected graph, where $V$ is the set of vertices and A the set of directed edges, and where (v, w) indicate a directed edge from $v$ to $w$. The Eulerian circuit problem for a directed graph consists in finding a directed circuit that traverses every edge of this graph exactly once or deciding no such circuit exists.

It’s possible to show that such a circuit exists if and only if the strongly connected directed graph has, for each vertex $v$, the same in-degree and out-degree. The algorithm is essentially the same.

Counting Eulerian Circuits in directed graphs

It’s possible to count the number of different Eulerian circuits in a directed graph. According to the BEST theorem (named after de Bruijn, van Aardenne-Ehrenfest, Smith and Tutte) [3], the number of Eulerian circuits in a directed graph can be given by [4]:

\[(1) \qquad ec(G) = t_w(G) \prod_{v \in V}(deg(v) - 1)!\]Where $deg(v)$ represents the in-degree (or out-degree) or a vertex $v$ and $t_w(G)$ is the number of arborescences rooted in a vertex $w$ (simply put, an arborescence is analogous to a spanning tree for a directed graph - but we can only include edges that are directed away from the root).

It’s possible to show that $t_w(G)$ is the same for any vertex $w$ if $G$ is Eulerian. We can compute $t_w(G)$ via the Matrix-Tree theorem [2], which says $t_w(G)$ is equal to the determinant of the Laplacian of $G$ without vertex $w$. Let’s try to understand the idea behind this equation.

The mapping from an arborescence to an Eulerian path can be made by the following. Let r be the root of a possible arborescence of $G$. Now, let r be the reference starting point for an Eulerian path in $G$ (note this is just for reference, since there’s no starting point in a circuit).

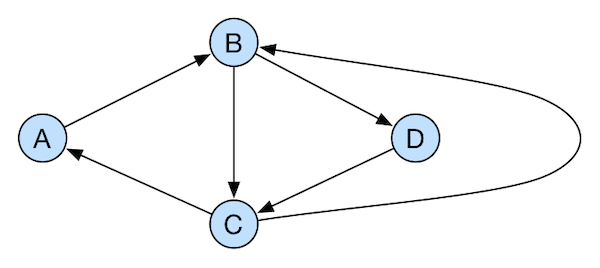

We say that an Eulerian path is associated with a given arborescence if for each vertex $v$, the last edge passing through $v$, say $(v, v’)$, belongs to the arborescence. This is more clear with an example. Consider the digraph from Figure 2. Here we’ll consider the arborescences rooted in $A$.

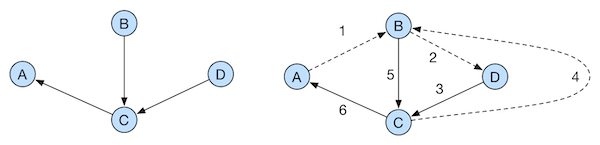

This graph has 2 possible arborescences depicted on the left in Figure 3 and Figure 4. In Figure 3, we can see that the edge $(B, D)$ has to be visited before $(B, C)$ because $(B, C)$ is in the arborescence.

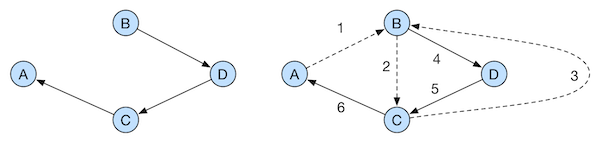

Now, in Figure 4, because it’s $(B, D)$ that’s in the arborescence, it has to be visited after we visit $(B, C)$.

Figure 4: Another of the arborescence of G and a corresponding Eulerian circuit

Note that there can be more than one Eulerian path to a given arborescence. If $B$ had more out-edges, we’d have multiple choices, since the arborescence only specifies the last edge to be taken, not the intermediate ones. More specifically, imagine $B$ had $k$ out-edges. Then we could traverse the first $k-1$ in any combination of orders, which leads to a total of $(k - 1)!$ ways of doing so.

The same applies to all other nodes. Due to properties of Eulerian circuits, the choice of the out-edge at a given node can be seen as independent of the choice at other nodes, so the total possible Eulerian circuits corresponding to any arborescence is given by the product of the degrees from equation (1), namely:

\[(2) \qquad \prod_{v \in V}(deg(v) - 1)!\]The key property of categorizing Eulerian circuits into arborescence classes is that they’re disjoint, that is, a Eulerian circuit corresponds to exactly one arborescence. This, in conjunction with the fact that the vertices degrees in Equation (2) are from the original graph, and hence independent of a arborescence, lead us to the two independent factors in equation (1).

Counting Eulerian Circuits in undirected graphs

Counting Eulerian circuits in undirected graphs is a much harder problem. It belongs to a complexity class known as #P-complete. This means that:

- It belongs to the #P class, which can informally be seen as the counting version of NP problems. For example: deciding whether a given graph has an Hamiltonian circuit (path that traverses all vertices exactly once) is a problem in the NP class. Counting how many Hamiltonian circuits existing in that graph is the corresponding problem in the #P class.

- It belongs to the #P-hard class, which means that any problem in #P can be reduced to it via a polynomial-time transformation. Valiant proved the first condition in [5] while Brightwell and Winkler proved the second in [6] by reducing another #P-complete problem (counting Eulerian orientations) to it.

Note that a problem in the #P class is as hard as the equivalent class in NP, because we can reduce a problem in NP to #P. For example, we can decide whether a graph has an Hamiltonian circuit (NP problem) by counting the number of circuits it has (#P problem). The answer will be “yes” if it the #P version returns a number greater than 0 and “no” otherwise.

Because the problem of counting Eulerian circuits in an undirected graph being in #P, we can conclude that there’s no efficient (polynomial time) algorithm to solve it unless P = NP.

Conclusion

In this post we covered Eulerian circuits in an informal way and provided an implementation for it in JavaScript. I spend quite some time to setup the JavaScript environment to my taste. I strongly prefer using typed JavaScript (with Flow) and using ES6 syntax. I decided to write it in JavaScript with the potential to create a step-by-step interactive tool to demonstrate how the algorithm works.

I was familiar with the concept of Eulerian circuits, but I didn’t remember the algorithms to solve it, even though I was exposed to one of them in the past. It was a good learning experience to write the code from scratch to really understand what I was doing.

This is the first time I see the #P complexity class. It’s always nice to learn about new theories when digging further on a specific topic.

References

- [1] Bioinformatics Algorithms: An Active Learning Approach - Compeau, P. and Pevzner P.

- [2] Matrix-Tree Theorem for Directed Graphs - Margoliash, J.

- [3] Circuits and trees in oriented linear graphs - Aardenne-Ehrenfest, van T., Bruijn, de N.G.

- [4] Wikipedia - BEST Theorem

- [5] The complexity of computing the permanent - L. G. Valiant

- [6] Counting Eulerian circuits is #P-complete - Brightwell, G. and Winkler, P.