kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > De Bruijn Graphs and Sequences

De Bruijn Graphs and Sequences

26 Dec 2018

Nicolaas Govert de Bruijn was a Dutch mathematician, born in the Hague and taught University of Amsterdam and Technical University Eindhoven.

Irving John Good was a British mathematician who worked with Alan Turing, born to a Polish Jewish family in London. De Bruijn and Good independently developed a class of graphs known as de Bruijn graphs, which we’ll explore in this post.

Definition

A de Bruijn graph [1] is a directed graph defined over a dimension $n$ and a set $S$ of $m$ symbols. The set of vertices in this graph corresponds to the $m^n$ possible sequences of symbols with length $n$ (symbols can be repeated).

There’s a directed edge from vertex $u$ to $v$ if the sequence from $v$ can be obtained from $u$ by removing $u$’s first element and then appending a symbol at the end. For example, if $S = \curly{A, B, C, D}$, $n = 3$ and $u = ABC$, then there’s an edge from $ABC$ to $BCA$, $BCB$, $BCC$ and $BCD$ (or $BC*$ for short).

Properties

We can derive some basic properties for de Bruijn graphs.

Property 1. Every vertex has exactly $m$ incoming and $m$ outgoing edges.

We saw from the example above that $ABC$ had edges to any vertex $BC*$, where $*$ represents any of the $m$ symbols in $S$. Conversely, any sequence in the form $*AB$ can be transformed into $ABC$, by dropping the first symbol and appending $C$.

Property 2. Every de Bruijn graph is Eulerian.

In our last post we discussed Eulerian graphs and learned that a necessary and sufficient condition for a directed graph to have an Eulerian cycle is that all the vertices in the graph have the same in-degree and out-degree and that it’s strongly connected. The first condition is clearly satisfied given the Property 1 above.

To see that a de Bruijn graph is strongly connected, we just need to note that it’s possible to convert any sequence into another by removing the first character and replacing the last with the appropriate one in at most n steps. For example, given the string $ABC$, we can convert it to $BDD$ by doing $ABC \rightarrow BCB \rightarrow CBD \rightarrow BDD$. Since each such step corresponds to traversing an edge in the de Bruijn graph, we can see it’s possible to go from any vertex to another, making the graph strongly connected.

Property 3. A de Bruijn graph over the set of symbols $S$ and dimension $n$ is the line graph of the de Bruijn graph over set $S$ and dimension $n - 1$.

A line graph of a given graph $G$ has vertices corresponding to edges in $G$, and there are edges between two vertices if the corresponding edges in $G$ share a vertex. More formally, let $G = (V, E)$ be an undirected graph. The line graph of $G$, denoted by $L(G)$ has a set of vertex $V’$ corresponding to $E$. Let $u’$, $v’$ be two vertices from $V’$, corresponding to edges $e_1$ and $e_2$ in E. There’s an edge between $u’$ and $v’$ if $e_1$ and $e_2$ have one vertex in common.

It’s possible to generalize this to directed graphs by changing the definition of edges slightly: let $u’$, $v’$ be two vertices from $V’$, corresponding to the directed edges $e_1 = (a, b)$ and $e_2 = (c, d)$ in $E$. Then there’s a directed edge from $u’$ to $v’$ if and only if $b = c$.

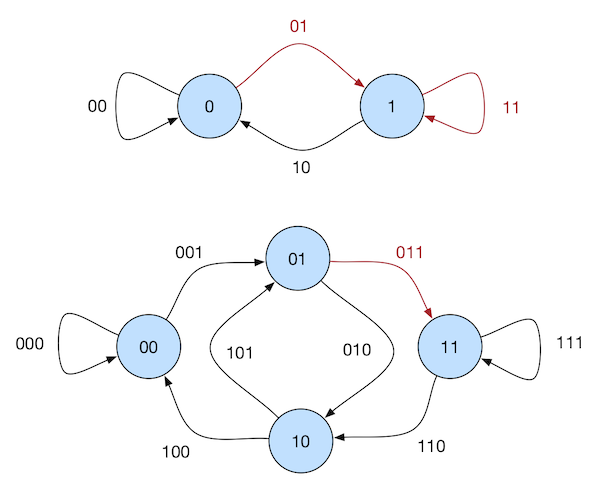

We can gain an intuition on Property 3 by looking at an example with set $S = \curly{0, 1}$ and constructing a de Bruijn graph with $n = 2$ from one with $n = 1$. In Figure 1, the vertices from $n = 2$ are the labeled edges of $n = 1$. The edges in $n = 2$ correspond to the directed paths of length 2 in $n = 1$. We highlighted in red one of such paths. In $n = 1$, the path is given by $(0, 1)$ and $(1, 1)$, which became the edge $(01, 11)$ (labeled $011$) in $n = 2$.

This shows that the de Bruijn graph for $n = 2$ is the line graph of the $n = 1$ one.

Property 4. Every de Bruijn graph is Hamiltonian.

By Property 2 we know every de Bruijn graph has an Eulerian cycle. We’ll show that an Eulerian cycle in a de Bruijn graph in dimension $n$ corresponds to an Hamiltonian path in dimension $n + 1$.

Recall that in the Eulerian cycle for $n$ we visit every edge exactly once. Now consider two consecutive edges in the Eulerian cycle, $(u, v)$ and $(v, w)$. By Property 3, these correspond to vertices $(u, v)’$ to vertex $(v, w)’$ in dimension $n + 1$ and there’s an edge from the former to the latter since they share vertex $v$. Thus the Eulerian cycle in $n$ is a Hamiltonian cycle in $n + 1$.

De Bruijn Sequence

The de Bruijn sequence of dimension $n$ on a set of symbols $S$, denoted $B(S, n)$, is a cyclic sequence obtained by visiting the Hamiltonian cycle of a de Bruijn graph over $S$ and dimension $n$.

Let the Hamiltonian cycle be $H = v_1, v_2, \cdots, v_{2^n}, v_1$. We initialize $B(S, n)$ with the label of $v_1$. Then we extend it with the label of $v_2$, but the first $n - 1$ characters of $v_2$’s label are the same as the last $n - 1$ of $v_1$’s label, so we just append the last character of $v_2$’s label.

We proceed along the cycle. When we finish, the last $n$ characters of the sequence will be exactly the first $n$ (they correspond to $v_1$’s label), so we can discard the last $n$ characters and “join” the endpoints of the sequence to form a cyclic sequence.

There are two interesting properties of $B(S, n)$ . First, it’s length is $\abs{S}^n$. Note that the size of the Hamiltonian cycle is $\abs{S}^n + 1$. We started with label of $v_1$ for a length of $n$ and then incremented the sequence by 1 for the other $\abs{S}^n$ vertices, for a total of $\abs{S}^n + n$, but we trimmed the last $n$ characters before joining, thus obtaining a $\abs{S}^n $ sequence.

Second, every sequences of symbols from $S$ and length $n$ is contained in $B(S, n)$. Each of these strings is a vertex in the de Bruijn graph, which is covered by the Hamiltonian cycle.

Since $\abs{S}^n$ is also the number of distinct sequences of length $n$, we claim that $B(S, n)$ is the shortest sequence possible that contain all the $n$-length sequences. To see why, let $B$ be a de Bruijn sequence. We can assign an index $p$ to each sequence $s$ of length $n$ based on where it appears in $B$, that is, $s = B[p : p + n - 1]$. Since each of the $\abs{S}^n$ sequences are distinct, they cannot have the same index $p$. Hence, there must be at least $\abs{S}^n$ indexes, and thus $B$ must be at least that long.

Applications

Cracking Locks

A de Bruijn sequence can be used to brute-force a lock without an enter key, that is, one that opens whenever the last n digits tried are correct. A naive brute force would need to try all $\abs{S}^n$ typing n digits every time, for a total of $\abs{S}^n$. Using a de Bruijn sequence we would make use of the overlap between trials, and only need to type $\abs{S}^n$ digits in total.

Finding the Least Significant Bit

The other interesting application mentioned in [2] is to determine the index of the least significant bit in an unsigned int (32-bits). The code provided is given by:

unsigned int v;

int r;

static const int MultiplyDeBruijnBitPosition[32] =

{

0, 1, 28, 2, 29, 14, 24, 3, 30, 22, 20, 15, 25, 17, 4, 8,

31, 27, 13, 23, 21, 19, 16, 7, 26, 12, 18, 6, 11, 5, 10, 9

};

r = MultiplyDeBruijnBitPosition[((uint32_t)((v & -v) * 0x077CB531U)) >> 27];Let’s understand what the code above is doing. For now, let’s assume v > 0 and we’ll handle v = 0 as a special case later.

In the code above, (v & -v) has the effect of “isolating” the least significant bit. Since v is unsigned, -v is its two’s complement, that is, we complement the digits of v (~v) and add one. Let p be the position of the least significant digit in v. The bits in positions lower than p will be 1 in ~v, and in position p it’s a 0. When incremented by 1, they’ll turn into 1 in position p and 0 in the lower positions. In the positions higher than p, v and -v will be have complementary bits. When doing a bitwise AND, the only position where both operands have 1 is p, hence it will be the number (1 << p) (or 2^p).

Then we multiply the result above by 0x077CB531U which is the de Bruijn sequence $B(\curly{0, 1}, 5)$ in hexadecimal. In binary this is 00000111011111001011010100110001, which is a 32-bit number. Because v & -v is a power of 2 (2^p), multiplying a number by it is the same as bit-shifting it to the left p positions. Then we shift it to the right by 27 positions, which has the effect of capturing the 5 most significant bits from the resulting multiplication. If we treat the number as a string of characters (note that most significant bits are the first characters), the left shift followed by the right shift is equivalent to selecting a “substring” from position p to p+5.

For example, if p = 13, a left shift on 00000111011111001011010100110001 would result in 10010110101001100010000000000000. Then a right shift of 27, would pick the 5 leftmost bits, 10010. If we treat 00000111011111001011010100110001 as a string, 10010 shows up as a substring 0000011101111[10010]11010100110001 in positions [13, 17].

Since this is a de Bruijn sequence for n = 5, every substring of length 5 corresponds to a unique 5-bit number and conversely every 5-bit number is present in this sequence. Now we just need to keep a map from the 5-bit number we obtained via the bit manipulation to the actual number we wanted, which we store in MultiplyDeBruijnBitPosition. Since 10010 is 18, we’ll have an entry MultiplyDeBruijnBitPosition[18] = 13.

Finally, for the special case where v = 0, we have that v & -v is 0 and the algorithm will return 0.

Assembling DNA Fragments

In [3] Compeau and Pevzner proposed a method to assemble fragments of DNA into its original form. The problem can be modeled as the k-universal circular string problem.

Definition: Consider a list of sequences $s_1, s_2, \cdots, s_n$, each of which having the same size $k$, having the property that $s_i$’s suffix and $s_{i+1}$’s prefix overlap in $k-1$ positions. That is, the last $k-1$ characters in $s_i$ are the same as the first $k-1$ characters in $s_{i+1}$. We are given the sequences in no particular order. The objective is to find a composed string $S$ which is the result of the overlap of $s_1, s_2, …, s_n$ in order.

This problem can be modeled as a de Bruijn graph where each sequence is associated with a vertex. If sequence $s_i$’s suffix and $s_j$’s prefix overlap in $k-1$ positions, we add a directed edge from vertex $s_i$ to $s_j$. We then find an Hamiltonian path in the de Bruijn graph and the order in which the vertices are visited will give us the desired string.

Variants: The Super-permutation

One variant to the de Bruijn sequence problem is to, instead of finding a universal sequence containing all possible sequences of length $n$, find one containing all the permutations of the symbols in S. Instead of the $\abs{S}^n$ sequences as input, we’ll have $\abs{S}!$ sequences. This is know as the Super-permutation problem.

For example, for $S = {1, 2}$, it wants to find a sequence containing: $12$ and $21$. The sequence $121$ is a possible solution. For $S = {1, 2, 3}$, we have now $123, 132, 213, 231, 312$ and $321$. The shortest $123121321$. John Carlos Baez tweets about this problem in [4]. Finding the shortest sequence that includes all permutations is an open problem!

The optimal solution is known for $n$ up to 5. The best known lower bound for this problem is $n! + (n−1)! + (n−2)! + n − 3$ while the upper bound is $n! + (n−1)! + (n−2)! + (n−3)! + n − 3$ [5].

Conclusion

In this post I was mainly interested in learning more about de Bruijn graphs after reading about them in Bioinformatics Algorithms by Compeau and Pevzner [3]. I ended up learning about de Bruijn sequences and realized that the problem was similar to one I read about recently on John’s Twitter. It was a nice coincidence.