kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Notes on JavaScript Interpreters

Notes on JavaScript Interpreters

01 Jun 2017

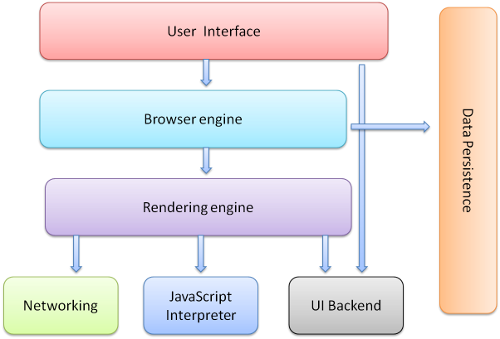

In a previous post, Notes on how browsers work, we studied the high-level architecture of a browser, specifically the Rendering Engine. We used the following diagram,

In this post we’ll focus on the JavaScript interpreter part. Different browsers use different implementations of the interpreters. Firefox uses SpiderMonkey, Chrome uses V8, Safari uses JavaScriptCore, Microsoft Edge uses Chakra, to name a few. V8 is also used as a standalone interpreter, most notably by Node.js.

These interpreters usually comply to one of the versions of the ECMAScript, which is a standardization effort of the JavaScript language. ECMA-262 is the document with the specification. As it happens with other languages, from their first inception, design flaws are identified, new development needs arise, so the language spec is always evolving. For that reason, there are a few versions of ECMAScript. Most browsers support the 5th edition, also known as ES5.

There’s already the 7th edition (as of 2016), but it takes time for browsers to catch up. Because of that, JavaScript programs that are capable of translating newer specs into ES5 were created, such as Babel. The advantage of using this technique, also known as transpiling, is that developers can use newer versions of the step, such as ES6, without depending on browser support. Disadvantages include the extra complexity by adding a new step in the deployment process and it makes harder to debug since it’s hard to map errors that happen in the transformed code back to the original source.

Section 8.4 of the ECMA-262 describes the execution model of JavaScript:

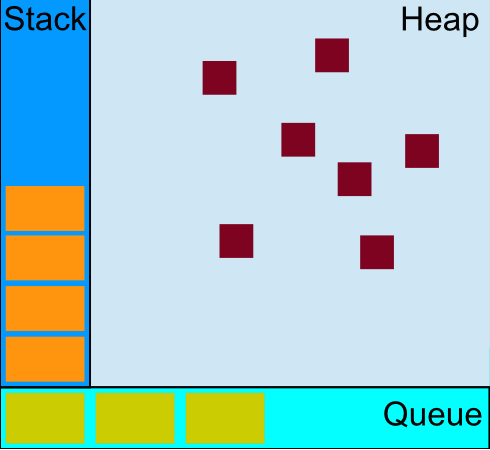

A Job is an abstract operation that initiates an ECMAScript computation when no other ECMAScript computation is currently in progress. A Job abstract operation may be defined to accept an arbitrary set of job parameters. Execution of a Job can be initiated only when there is no running execution context and the execution context stack is empty. A PendingJob is a request for the future execution of a Job. A PendingJob is an internal Record whose fields are specified in Table 25. Once execution of a Job is initiated, the Job always executes to completion. No other Job may be initiated until the currently running Job completes. However, the currently running Job or external events may cause the enqueuing of additional PendingJobs that may be initiated sometime after completion of the currently running Job. MDN’s Concurrency model and Event Loop [2] describes this spec in a more friendly way. As in other programming environments such as C and Java, we have two types of memory available: the heap and the stack. The heap is the general purpose memory and the stack is where we keep track of scopes for example when doing function calls.

In JavaScript we also have the message queue, and for each message in the queue there is an associated function to be executed.

The event loop

The execution model is also called the event loop because of the high-level working of this model:

while (queue.waitForMessage()) {

queue.processNextMessage();

}When the stack is empty, the runtime processes the first message from the queue. While executing the corresponding function, it adds an initial scope to the stack. The function is guaranteed to execute “atomically”, that is, until it returns. The execution might cause new messages to be enqueued, for example if we call

setTimeout(

function() {

console.log('hello world');

},

1000

);The callback passed as the first argument to setTimeout() will be enqueued, not stacked. On the other hand, if we have a recursive function, such as a factorial:

function factorial(n) {

if (n == 0) {

return 1;

}

setTimeout(

function() {

console.log('enqueued', n);

},

0

)

return factorial(n - 1) * n;

}

console.log(factorial(10));The recursive calls should all go to the same stack, so they will be executed to completion, that is until the stack is empty. The calls provided to setTimeout() will get enqueued and be executed only after the value of the factorial gets printed.

In fact, using setTimeout() is a common trick to control the execution order of functions. For example, say that function A called B and B calls another function C. If B calls C normally, then C will have to finish before B returns, as the sample code below:

function a() {

console.log('a before b');

b();

console.log('a after b');

}

function b() {

c();

}

function c() {

console.log('c');

}

// Running this in node.js outputs

// a before b

// c

// a after b

a();In case we want to finish executing A first, then B can call C using setTimeout(C, 0), because then it will be enqueued, and then both A and B will finish until a new message is processed from the queue, as the code below:

function a() {

console.log('a before b');

b();

console.log('a after b');

}

function b() {

setTimeout(c, 0);

}

function c() {

console.log('c');

}

// Running this in node.js outputs

// a before b

// a after b

// c

a();Web Workers

We discussed Web Workers in a previous post, in which we mentioned that it’s a separate thread that shares no memory with the main thread. In fact, according to [2], it has its own stack, heap and queue. It doesn’t violate the execution model of the main thread because communications must be done via a publisher/subscriber API, which means communicating between two threads is subject to the queueing.

V8

Beyond the spec, each JavaScript engine is free to implement feature the way they want. V8’s architecture is described in their wiki page [3], so we can study some of its key components.

Fast Property Access

In JavaScript, structures like Object can be mutated (added and removed properties) in runtime. Implementing them as hashtables can lead to performance problems when accessing properties of these structures. Compare that to compiled languages like Java in which instances of a class can be allocated with all its members in a single chunk of memory and accessing properties of objects consists in adding an offset to the object’s pointer.

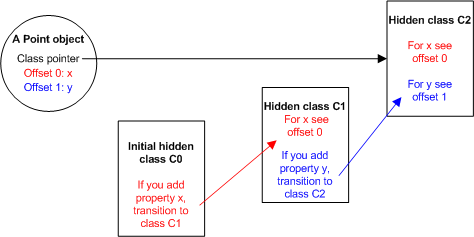

V8 optimizes the Object allocation by creating hidden classes. It makes use of the fact that properties are mutated in the same pattern. For example in

https://gist.github.com/kunigami/86a3c04ef2399810c9194f4a30ae5916

In this case, we always insert the property x and then y. V8 starts with an empty class C0 when the object is first created. When x is assigned, it creates another class C1 with property x and that points to C0. When y is assigned, it creates yet another class C2 with property y that point to C1.

When the Point constructor is finished, it will be an instance of C2. It has to instantiate 3 objects one from C0, then C1, then C2.

Accessing property y is an adding an offset operation, while accessing property x is two offset operations, but still fast than a table lookup. Other instances of Point will share the same class C2. If for some reason we have a point with only x set, then it will be an instance of class C1. This sharing of structures resembles the persistent data structures that we studied previously.

Another interesting property of this method is that it doesn’t need to know in advance whether the code has indeed a pattern in mutating objects. It’s sort of a JIT compilation.

Dynamic Machine Code Generation

According to [3]:

V8 compiles JavaScript source code directly into machine code when it is first executed. There are no intermediate byte codes, no interpreter.

Efficient Garbage Collection

We wrote about V8’s memory management in a previous post.

Conclusion

In this post we revisited a bit of the history of JavaScript and ECMAScript. We also studied the event loop model that is part of the spec and finally saw some aspects of one of the JavaScript engines, V8.