kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Notes on how browsers work

Notes on how browsers work

09 Oct 2015

In this post, I’d like to share some notes from articles about how modern browser works, in particular the rendering process.

All the aforementioned articles are based on open source browser code, mainly Firefox and Chrome. Chrome uses a render engine called Blink, which is a fork to Webkit used by other browsers like Safari. It seems to be the one with more documentation, so we’ll focus on this particular engine. The main sources are [1, 2 and 3]. They cover this subject in much more depth, so I recommend the read for those interested in more details.

The Big Picture

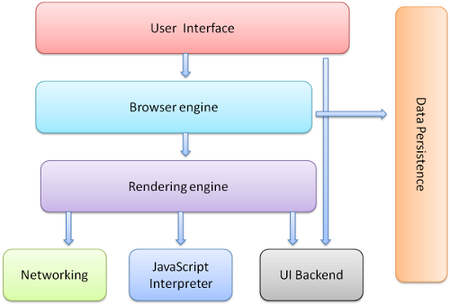

First, let’s take a look in an high-level architecture of a browser:

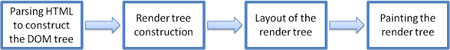

As we said before, our focus will be on the Rendering Engine. According to [1], it consists of the following steps:

and we’ll use these steps as our sections to come.

1. Parsing HTML to construct the DOM tree

This step consists in converting a markup language in text format into a DOM tree. An interesting observation is that HTML is not a Context Free Grammar because of its forgiving nature, meaning that parsers should accept mal-formed HTML as valid.

The DOM tree is a tree containing DOM (Document Object Model) elements. Each element corresponds to a tag from the HTML markup.

As we parse the HTML text, we might encounter the tags that specify two common resources that enhance basic HTML: CSS and JavaScript. Let’s cover those briefly:

Parsing CSS

CSS is a Context-free Grammar, so Webkit is able to rely on tools like Flex (lexical analysis generator) and Bison (parser generator) to parse the CSS file. The engine uses hashmaps to store the rules, so it can perform quick lookups.

Parsing Javascript

When the parser encounters a script tag, it starts downloading (if it’s an external resource) and parsing the JavaScript code. According to specs, downloading and parsing occurs synchronously, blocking the parsing process of the HTML markup.

The reason is that executing the script might trigger the HTML body to be modified (e.g. via document.write()). If the JavaScript doesn’t modify the HTML markup, Steve Souders suggests moving the script tags to the bottom of the page or adding the defer attribute to the script tag [4]. He has two test pages to highlight the load times for these distinct approaches: bottom vs. top.

In practice, according to Garsiel [1], browsers will do speculative parsing, trying to download script files in parallel to the main HTML parsing. This process does not start though until all stylesheet files are processed.

2. Render tree construction

While constructing the DOM tree, the browser also builds another tree called render tree. Each node in this tree, called render object, represents a rectangular area on the screen.

There’s not necessarily a 1:1 correspondence between DOM nodes and render nodes. For example a select tag has multiple render nodes, whereas hidden DOM elements (with the CSS property display set to none) do not have a corresponding render node.

Since each node represents a rectangle, it needs to know its offset (top, left) and dimensions (height, width). These values depend on several factors, including the CSS properties like display, position, margin and padding and also the order in which they appear in the HTML document.

The process of filling out these parameters is called the layout or reflow. In the next section we’ll describe this process in more details.

3. Layout of the render tree

Rectangle size. For each node, the size of the rectangle is constructed as follows:

- The element’s width is whatever value is specified in the CSS or 100% of the parent’s width

- To compute the height, it first has to analyse the height of its children, and it will have the height necessary to enclose them, or whatever value is specified in the CSS.

A couple of notes here: the height is calculated top-down, whereas the width is calculated bottom-up. When computing the height, the parent only looks at the immediate children, not descendants. For example, if we have

<div style='background-color: green; width: 400px'>

A

<div style='background-color: red; width: 500px; height: 100px'>

B

<div style='background-color: blue; height: 150px'>

C

</div>

</div>

</div>The green box (A) will have the height enough to contain the red box (B), even though the blue box (C) takes more space than that. That’s because B has a fixed height and C is overflowing it. If we add the property overflow: hidden to B, we’ll see that box A is able to accommodate B and C.

Some properties may modify this default behavior, for example, if box C is set to position absolute or fixed, it’s not considered in the computation of B’s height.

Rectangle offset. To calculate the offset, processes the nodes of the tree in order. Based on the elements that were already processed, it can determine its position depending on the type of positoning and display the element has. If it’s display:block, like a div with default properties, it’s moved to the next and the left offset is based on the parent. If it’s display is set to inline, it tries to render in the same line after the last element, as long as it fits within the parent container.

Some other properties besides display can also change how the position is calculated, the main ones being position and float. If position is set to absolute and the top is defined, the offset will be relative to the first ancestral of that component with position set to relative. The same works for the property left.

Whenever a CSS changes happens or the DOM structure is modified, it might require a new layout. The engines try to avoid the re-layout by only processing the affected subtree, if possible.

4. Painting the render tree

This last step is also the most complex and computationally expensive. It requires several optimizations and relies on the GPU when possible. In this step, we have two new conceptual trees, the render layer tree and the graphics layer tree. The relationship of the nodes in each tree is basically:

DOM Element > Render Object > Render Layer> Graphics Layer.

Render layers. exist so that the elements of the page are composited in the correct order to properly display overlapping content, semi-transparent elements, etc. A render layer contains one or more render object .

Graphics layers. uses the GPU for painting its content. One can visualize layers by turning on the “Show composited layer borders” in Chrome DevTools (it’s under the Rendering Tab, which is only made visible by clicking on the drawer icon >_). By default, everything is rendered in a single layer, but things like 3D CSS transforms trigger the creation of new layers. Wiltzius [2] provides a sample page where one can visualize an extra layer:

http://www.html5rocks.com/en/tutorials/speed/layers/onelayer.html

A render layer either has its own layer, or inherits one from its parent. A render layer with its own layer is called compositing layer.

Rendering process. occurs in two phases: painting, which consists of filling the contents of a graphics layer and compositing (or drawing) which consists in combining graphics layers into a single image to display in the screen.

Conclusion

I was initially planning to study general JavaScript performance profiling. In researching articles on the internet, I’ve found a number of them are related to making websites more responsive by understanding and optimizing the browser rendering process. I’ve realized there was a lot to be learned about this process and I could benefit from studying this subject.

A lot of the articles come from different sources, but a few authors seem to always been involved in them. Paul Irish and Paul Lewis are two of the folks who I’ve seen in several articles (see Additional Resources), and they have a strong presence online and might be worth following them if you’re interested in the subject.

References

- [1] HTML5 - How Browsers Work: Behind the scenes of modern web browsers

- [2] HTML5 Rocks - Accelerated Rendering in Chrome

- [3] Chromium Design Documents - GPU Accelerated Compositing in Chrome

- [4] High Performance Web Sites: Essential Knowledge for Front-End Engineers

Additional Resources

Chrome Developer Tools (for rendering):

- Speed Up JavaScript Execution

- Analyze Runtime Performance

- Diagnose Forced Synchronous Layouts

- Profiling Long Paint Times with DevTools’ Continuous Painting Mode

Google Web Fundamentals:

- Stick to compositor-only properties and manage layer count

- Avoid large, complex layouts and layout thrashing

Browser rendering performance:

- CSS Triggers - To determine whether a CSS property triggers layout

- Accelerated Rendering in Chrome

- The Runtime Performance Checklist

- How (not) to trigger a layout in WebKit

General JavaScript performance (mainly for V8):

- Performance Tips for JavaScript in V8

- IRHydra2 - Displays intermediate representations used by V8