kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Hadamard Factorization Theorem

Hadamard Factorization Theorem

30 Aug 2025

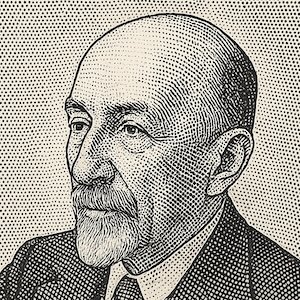

Jacques Salomon Hadamard was a French mathematician. Among his contributions, Hadamard proved the prime number theorem and has his name on the Hadamard product (element-wise product of matrices) and the Hadamard matrices. Even though he didn’t work in quantum mechanics, Hadamard gates are also named after him because its matricial representation is a Hadamard matrix.

Being of Jewish descent, in 1941 Hadamard left France for the United States during the antisemitic Vichy government. He returned in 1945 after the end of World War II.

In this post I’d like to explore the Hadamard Factorization Theorem.

Recap

In the post Weierstrass Factorization Theorem [2] we learned that an entire function $f(z)$ with $m$ zeros at the origin and other zeros $a_1 \le a_2 \le \cdots$ with $\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \abs{a_n} = \infty$ can be written as:

\[(1) \quad f(z) = z^m e^{g(z)} \prod_{n = 1}^\infty E_{m_n}\left(\frac{z}{a_n}\right)\]where

\[E_{n}(w) = \left(1 - w\right) e^{\sum_{k=1}^n w^k/k}\]For some $g(z)$ and set of naturals $m_n$. In that post we also considered a special case: if $h$ is such that

\[(2) \quad \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{\abs{a_n}^{h + 1}}\]converges, then we can have all $m_n = h$. In this case the product

\[\prod_{n = 1}^\infty E_{h}\left(\frac{z}{a_n}\right)\]Is defined as the canonical product and if $h$ is the smallest natural number for which $(2)$ converges, then it’s defined as the genus of the canonical product.

Genus and Order

We can generalize the definition of genus of the canonical product for the entire function. The genus of an entire function $f(z)$ is the maximum between the degree of $g(z)$ in $(1)$ and the of genus of the canonical product. When we say genus without qualifications we’ll refer to the one of the entire function and will also denote it by $h$.

Recall that in [1] we wanted to find a product decomposition of $\sin(\pi z)$. We started from its zeros to obtain $(1)$ and then were able to find that the genus of the canonical product was $1$ and by some tricks we were able to find $g(z)$ was constant (degree 0).

In general however, there’s no constraint between the genus of the canonical product and the degree of $g(z)$. But if we are able to find the genus of the entire function, that’s a much stronger result, because then we know both the genus of the canonical product and the degree of $g(z)$ are smaller than that.

The order of an entire function indicates how fast a function grows with its input. It’s formal definition is as follows: let $M(r)$ be the maximum value of $\abs{f(z)}$ on the circumference $\abs{z} = r$. The order of $f(z)$, denoted by $\lambda$ is defined as:

\[(3) \quad \lambda = \lim \sup_{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\log \log M(r)}{\log r}\]Recalling that $\lim \sup_{n \rightarrow \infty} z_n = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} (\sup_{m \ge n} z_n)$. It’s the upperbound of a sequence that might not convent to a single finite limit otherwise. Note that $\lambda$ is not necessarily an integer.

With these definitions, the Hadamard theorem is extremely simple to state: $h \le \lambda \le h + 1$. So for example, if we find that $\lambda = 1.345$, because $h$ is integer, it must be that $h = 1$.

Properties

Before we move to Hadamard’s theorem proof, let’s work on some properties of orders in order to facilitate that. The definition of order is expressed as a function of $M(r)$. We can turn it around and express the latter as a function of $\lambda$:

Lemma 1. Let $M(r)$ be the maximum value of $f(z)$ for $\abs{z} = r$ and $\lambda$ the order of $f(z)$. Then for any $\epsilon \gt 0$, there is a sufficiently large $r$ such that:

\[M(r) \lt e^{r^{\lambda + \epsilon}}\]We can now solve for $M(r)$ and we'll obtain the desired result.

In this form is a bit easier to see that the order of a function denotes its rate of super exponential (double expontential) growth. Not surprisingly, relatively slow growth functions like constants and polynomials have order 0.

Lema I. Let $f(z)$ be a polynomial. Then it has order 0.

If however we exponentiate that polynomial, the order matches the growth of the polynomial itself:

Lemma 2. Let $g(z)$ be a polynomial of degree $h$. Then $e^{g(z)}$ has order $\lambda = h$.

Since $\lambda$ denotes exponential growth, intuitively multiplying two functions doesn’t create a faster growing function:

Lemma 3. Let $f$ and $g$ be entire functions with order $\lambda_f$ and $\lambda_g$. Then $h = fg$ is an entire function and its order is such that $\lambda_h \le \max(\lambda_f, \lambda_g)$.

Applying $\log$ to both sides: $$ \log M_h(r) \le \log M_f(r) + \log M_g(r) $$ Without loss of generality, suppose that $M_f(r) \ge M_g(r)$, so we have: $$ \log M_h(r) \le 2 \log M_f(r) $$ Apply $\log$ again, divide by $\log r$: $$ \frac{\log \log M_h(r)}{\log r} \le \frac{log{2}}{\log r} + \frac{\log \log M_f(r)}{\log r} $$ Take $\lim \sup_{r \rightarrow \infty}$ and the first fraction on the right side goes to zero, leaving us with: $$ \lambda_h \le \lambda_f $$ but recall we assumed $M_f$ was the larger of $M_f$ and $M_g$ and since the operations we performed preserve relative order, $\lambda_f$ is the larger of $\lambda_f$ and $\lambda_g$. QED.

As a special case, if one of the functions being multiplied is slow growth, then it doesn’t contribute at all to the super exponential growth of the resulting function:

Lemma 4. Let $g$ be an entire function of order $\lambda_g$ and $p$ a polynomial. Then $f = pg$ is an entire function with order $\lambda_f = \lambda_g$.

We have that $M_f(r) = \max_{\abs{z} = r}{(p(z) g(z))}$. Let $w \in \curly{\abs{z} = r}$ be such that $M_g(r) = g(w)$. Then $M_f(r) \ge p(w) M_g(r)$. Apply $\log$: $$ \log M_f(r) \ge \log p(w) + \log M_g(r) $$ Apply $\log$ again and using Lemma 10: $$ \log \log M_f(r) \le \max{\log \log p(w), \log \log M_g(r)} $$ dividing by $\log r$ and taking $\lim \sup_{r \rightarrow \infty}$, the first argument to $\max$ will vanish so it will be dominated by the second and thus $\lambda_f \ge \lambda_g$.

Hadamard’s Theorem Proof

The first step before proving the theorem is to reduce the problem. To do that, we need Lemma 5:

Lemma 5. Let $f(z)$ be a function with $m$ zeroes equal to $0$. Let $g(z)$ be such that $f(z) = z^m g(z)$. Then $f$ and $g$ have the same order.

The lemma says that the order of a function doesn’t depend on the zeros equal to 0. Since the genus of an entire function also only depends on $g(z)$ and $E_h(z)$ (but not on $z^m$), the zeros equal to 0 also do not matter. Thus, for the purposes of the proof, we can assume $f(z)$ does not contain any zeros equal to $0$, and by Weierstrass theorem it has the form:

\[f(z) = e^{g(z)} \prod_{n = 1}^\infty E_{m_n}\left(\frac{z}{a_n}\right)\]The theorem can be broken down into two parts, Lemma 6 and Lemma 7:

Lemma 6. Let $f(z)$ be an entire function of genus $h$. Then it has order $\lambda \le h + 1$.

We can show that: $$ (6.1) \quad \log \abs{E_h(u)} \le (2h + 1) \abs{u}^{h + 1} $$ We have that: $$ \abs{P(z)} = \prod_{n} \abs{E_{h}\left(\frac{z}{a_n}\right)} $$ Let $M_P(r)$ the maximum value of $P(z)$ for $\abs{z} = r$, so that: $$ M_P(r) = \prod_{n} \abs{E_{h}\left(\frac{r}{a_n}\right)} $$ Apply $\log$, replace $(6.1)$: $$ \log M_P(r) = \sum_{n} \log \abs{E_{h}\left(\frac{r}{a_n}\right)} \le \sum_{n} (2h + 1) \abs{\frac{r}{a_n}}^{h + 1} $$ Extract terms out of the sum: $$ \log M_P(r) \le (2h + 1) r^{h + 1} \sum_{n} \frac{1}{\abs{a_n}^{h + 1}} $$ Because $f(z)$ has genus $h$, the canonical product has genus at most $h$, so the sum is convengent by definition. Let's call it $S$: $$ \log M_P(r) \le (2h + 1) r^{h + 1} S $$ Apply $\log$ again, divide by $\log r$: $$ \frac{\log \log M_P(r)}{\log r} = \frac{\log(2h + 1)}{\log r} + (h + 1) + \frac{\log S}{\log r} $$ If we take $\lim \sup_{n \rightarrow \infty}$ the first and third terms vanish and we're left with $h + 1$ as an upperbound for $P(z)$'s order. QED.

Lemma 7. Let $f(z)$ be an entire function of order $\lambda$. Then it has genus $h \le \lambda$.

We now wish to prove that $\abs{\nu(\rho)} \le \rho^{\lambda + \epsilon}$ for any $\epsilon \gt 0$ and a sufficiently large $\rho$. We use Jensen's formula: $$ \log {\abs{f(0)}} = - \sum_{i = 1}^n \log \left(\frac{R}{\abs{a_i}}\right) + \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} \log \abs{f(R e^{i\theta})} d\theta $$ Where $a_1, \cdots, a_n$ are the zeros of $f(z)$ in the interior of $\abs{z} \lt R$. Let's use $R = 2 \rho$ and rearrange terms: $$ \sum_{i = 1}^n \log \left(\frac{2\rho}{\abs{a_i}}\right) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} \log \abs{f(2 \rho e^{i\theta})} d\theta - \log {\abs{f(0)}} $$ For every zero $a$ in $\nu(\rho)$ we have $\abs{a} \le \rho$, in which case $\log 2 \le \log (2\rho / \abs{a})$. If we sum over all over $a$ in $\nu(\rho)$ we get: $$ \abs{\nu(\rho)} \log 2 \le \sum_{a \in \nu(\rho)}^{n} \log (2\rho / \abs {a}) $$ But the set of zeros inside $\abs{z} \le 2 \rho$ is a superset of $\nu(\rho)$ so: $$ \abs{\nu(\rho)} \log 2 \le \sum_{i = 1}^n \log \left(\frac{2\rho}{\abs{a_i}}\right) $$ Now integrating $\abs{f(2\rho e^{i\theta})}$ over $\theta$ represents the points of the circumference $\abs{z} = 2\rho$, so we can use the upper bound $M_f(2\rho)$ to move it out of the integral: $$ \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} \log \abs{f(2 \rho e^{i\theta})} d\theta = \frac{\log M_f(2\rho)}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} d\theta = \log M_f(2\rho) $$ The value $M_f(2\rho)$ has the upperbound (Lemma 1): $$ M_f(2\rho) \le e^{(2\rho)^{\lambda + \epsilon / 2}} $$ Which holds for any $\epsilon \gt 0$, so we chose $\epsilon / 2$. Taking the log: $$ \log M_f(2\rho) \le (2\rho)^{\lambda + \epsilon / 2} $$ So far we have $$ \abs{\nu(\rho)} \log 2 \le (2\rho)^{\lambda + \epsilon / 2} - \log {\abs{f(0)}} = 2^{\lambda + \epsilon / 2} \rho^{\lambda + \epsilon / 2} - \log {\abs{f(0)}} $$ Define constants $\alpha = 2^{\lambda + \epsilon / 2}$ and $\beta = - \log {\abs{f(0)}}$ to simplify to: $$ \abs{\nu(\rho)} \log 2 \le \alpha \rho^{\lambda + \epsilon / 2} + \beta $$ Divide by $(\log 2) \rho^{\lambda + \epsilon}$, we have: $$ \frac{\abs{\nu(\rho)}}{\rho^{\lambda + \epsilon}} \le \frac{\alpha}{(\log 2) \rho^{\epsilon/2}} + \frac{\beta}{(\log 2) \rho^{\lambda + \epsilon}} $$ If we take $\lim_{\rho \rightarrow 0}$ the right hand side tends to 0, which means $\abs{\nu(\rho)} / \rho^{\lambda + \epsilon}$ so it must be that $\abs{\nu(\rho)} \lt \rho^{\lambda + \epsilon}$, since $\abs{\nu(\rho)}$ tends to infinity itself.

We finally conclude that $n \le \abs{\nu(\abs{a_n})} \le \abs{a_n}^{\lambda + \epsilon}$ or that $$ \frac{1}{n} \gt \frac{1}{\abs{a_n}^{\lambda + \epsilon}} $$ Elevating to the power $(h + 1)/(\lambda + \epsilon)$ gives us: $$ \frac{1}{n^{(h + 1)/(\lambda + \epsilon)}} \gt \frac{1}{\abs{a_n}^{h + 1 }} $$ Adding for all zeros: $$ \sum_{n} \frac{1}{n^{(h + 1)/(\lambda + \epsilon)}} \gt \sum_{n} \frac{1}{\abs{a_n}^{h + 1}} $$ Our hypothesis is that $\lambda \lt h + 1$, so we can choose $\epsilon$ small enough such that $\lambda + \epsilon \lt h + 1$ and that $(h + 1)/(\lambda + \epsilon) > 1$, which guarantees the left hand side converges and so does the right hand side, which proves that the genus of the canonical product is at most $h$.

This proves we can write $f(z)$ as: $$ \quad f(z) = e^{g(z)} \prod_{n = 1}^\infty E_{h}\left(\frac{z}{a_n}\right) $$ To complete the proof we still need to show that $g(z)$ has degree at most $h$ as well. We'll skip it, but the general idea [1] is to use the Poisson-Jensen formula and eventually prove that $g^{(h+1)}(z)$ is 0, which implies the degree is at most $h$.

Putting these 2 results together we can state Hadamard’s theorem:

Theorem 8. Let $f(z)$ be an entire function of genus $h$ and order $\lambda$. Then:

\[h \le \lambda \le h + 1\]Related Results

We can prove that if $f(z)$ is entire with a non-integer order, then for every $w \in \mathbb{C}$, there exists infinitely many $z$ such that $f(z) = w$.

Theorem 9. Let $g(z)$ be an entire function of non-integer order. Then $f(z)$ assumes every value infinitely many times.

By contradiction, assume $f_w(z)$ has a finite number of zeros $n$. Then we can factor those zeros out and obtain: $$ f_w(z) = h_w(z) \prod_{k=1}^n (z - a_k) $$ Where $h_w(z)$ is an entire function without zeros. By Lemma 4 in [2], it can be written as $e^{g_w(z)}$ for some polynomial $g_w(z)$ of degree $d$. From Lemma 2, we have that $h_w(z)$ has order $d$. Since the product us a polynomial of degree $n$, from Lemma 4, we get that $\lambda_{f_w} = \lambda_{h_w} = d$, and since constants don't change the order, $\lambda_{f} = d$, so we conclude that $\lambda_f$ is the integer $d$, a contradiction.

So we conclude that one our assumptions is wrong: that $f(z)$ has fractional order or that $g(z)$ has a finite number of zeros. Since there are examples of $f(z)$ with fractional order, for those $g(z)$ has to have an infinite number of zeros.

Conclusion

I first heard of Hadamard’s theorem when studying The Basel Problem. That was before I started studying complex analysis, a d I had also learned about holomorphic functions in the occasion.

I’m glad to have finally have understood the proof of Hadamard’s theorem, even though didn’t include the full proof here, I have a rough understanding of how it uses Jensen’s formula which in turn relies on the Poisson kernel formula studied in [3].

Ahlfors’ book was very hard to follow. It states Lemma 2 without proving, and it is definitely non-trivial. ChatGPT was extremely useful.

Appendix

Lemma 10. Let $A, B \in \mathbb{R}$. Then

\[\mbox{max}(\log A, \log B) \le \log(A+B) \le \log 2 + \mbox{max}(\log A, \log B)\]