kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > The Maximum Principle

The Maximum Principle

18 Jan 2025

This is a post with my notes on complex integration, corresponding to Chapter 4 in Ahlfors’ Complex Analysis.

In today’s post we’ll go over the Maximum Principle in Complex Analysis which states that a non-constant holomorphic function over an open set does not have a maximum value.

The maximum principle is one of those results that is counter-intuitive because of infinity (see Hilbert’s Hotel). How is it possible for a set to not have a maximum element? If we picture a set as a discrete and finite collection of numbers, then it’s indeed hard to “see” it.

For infinite sets, we have to rely on contradiction to prove it. For example, with $f(x) = 1 - 1/x$, for $x \in \mathbb{R}, x \gt 0$. What is the maximum value $f(x)$ can attain?

No matter how large $x$ is, $1/x$ is never 0, so $f(x) \lt 1$. Now suppose there is $x’$ for which $f(x’)$ is the maximum. It’s not hard to see that $f(x’ + 1) \gt f(x’)$, so we have a contradiction.

That’s why we need the concept of infimum and supremum (when mininum and maximum don’t exist).

I first learned about the max principle while studying real analysis, but it extends to complex analysis.

Formal Statement

Theorem 1. If $f(z)$ is a holomorphic and non-constant function in an open set $\Omega$, then $\abs{f(z)}$ has to maximum value.

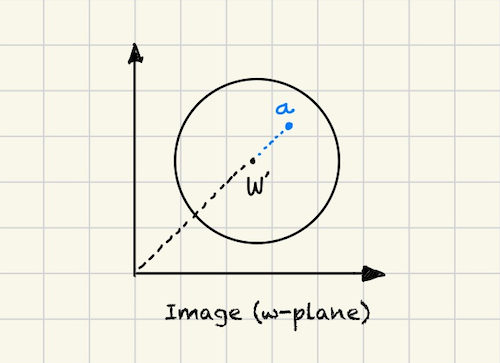

Now suppose there is $z'$ such that $f(z') = w'$ is maximum. Then there exists a disk $B = \curly{\abs{w - w'} \lt \delta}$ with $\delta \gt 0$ in $f(\Omega)$, since its open.

We can write $w'$ in polar form as $\abs{w'}e^{i\theta}$. Let $a = \abs{w'}e^{i\theta} + \epsilon e^{i\theta}$ as depicted in Figure 1.1. Then $\abs{a} = \abs{w'} + \epsilon \gt \abs{w'}$ which is a contradiction.

A variant of Theorem 1, which we can state as a corollary is:

Corollary 2. If $f(z)$ is continuous in a compact set $\Omega$ (closed and bounded) and holomorphic in the interior of $\Omega$, then $\abs{f(z)}$ attains a maximum for $z$ in the boundary of $\Omega$.

The Extreme value theorem states that a continuous function on a compact set has a maximum value.

Now we claim that this maximum value is attained for a point $z'$ at the boundary of $\Omega$. Suppose that it's not, that $z'$ is in the interior of $\Omega$. Since the interior $\Omega$ is open, and by hypothesis $f(z)$ is holomorphic and non-constant there, this would contradict Theorem 1.

The proofs rely on the Open Mapping Theorem which we studied in the last post of the series.

Schwarz Lemma

We can use Theorem 1 and Corollary 2 to prove the Schwarz Lemma:

Theorem 3. (Schwarz Lemma) Let $f(z)$ be a holomorphic function in $\abs{z} \lt 1$, with $\abs{f(z)} \le 1$ and $f(0) = 0$. Then

\[\abs{f(z)} \le \abs{z} \quad \mbox{and} \quad \abs{f'(0)} \le 1\]Moreover, if equality is attained in either of these inequalities, i.e., $\abs{f(z)} = \abs{z}$ or $\abs{f’(0)} = 1$, then

\[f(z) = cz\]Where $c$ is a constant with $\abs{c} = 1$.

We can do a holomorphic extension [3] of $g(z)$ to include $0$ via $g(0) = \lim_{z \rightarrow 0} g(z)$: $$\lim_{z \rightarrow 0} g(z) = \lim_{z \rightarrow 0} \frac{f(z)}{z} = \lim_{z \rightarrow 0} \frac{f(z) - f(0)}{z - 0}$$ The last equation being the definition of $f'(0)$, so $$ \begin{equation} g(z)=\left\{ \begin{array}{@{}ll@{}} f'(0), & z = 0 \\ \frac{f(z)}{z}, & z \ne 0 \end{array}\right. \end{equation} $$ is holomorphic in $\abs{z} \lt 1$. Now consider the set of points inside $\abs{z} \lt 1$ in a ring of radius $0 \lt r \lt 1$. For these points, we have that $\abs{z} = r$, so: $$\abs{g(z)} = \frac{\abs{f(z)}}{r} \le \frac{1}{r}$$ The last inequality is from the hypothesis. Consider the closed disk $\abs{z} \le r$. Since $g(z)$ is holomorphic and the close disk a compact set, $\abs{g(z)}$ obtains its maximum value at the boundary $\abs{z} = r$, so $\abs{g(z)} \le 1/r$ for a closed disk $\abs{z} \le r$ (including the $0$).

As we increase $r$, the upper bound of $\abs{g(z)}$ tighens and approaches $1$, so we can make $r \rightarrow 1$ to obtain $\abs{g(z)} \le 1$ in $\abs{z} \lt 1$. For $z \ne 0$ we get $\abs{f(z)} \le \abs{z}$. For $z = 0$ we get $f'(0) \le 1$.

If $g(z) = 1$ for some $\abs{z} \lt 1$, i.e. it attains its maximum inside an open disk, then $g(z)$ has to be constant. Otherwise it contradicts Theorem 1. Thus $g(z) = 1$ for all $\abs{z} \lt 1$. Then $g(0) = f'(0) = 1$ and $\abs{f(z)} = \abs{z}$ which is equivalent to saying $f(z) = cz$ for a constant $\abs{c} = 1$.

One way to interpret $f(z)$ with the above conditions is that it maps the unit open disk at the origin into the closed unit disk at the origin.

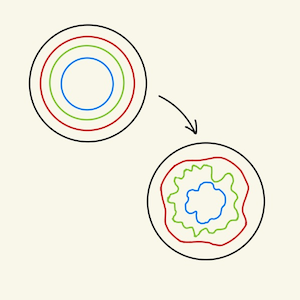

The theorem then says that we cannot strech the disk. It we look at the set of points in $\abs{z} = r$ in the domain, they’ll be mapped to points $\abs{w} \le r$ in the image. We can rotate these points around the origin, move them closer to the origin, but they cannot be moved further away. This idea is being captured on the post’s thumbnail.

It’s possible to generalize the constraints on this theorem by transforming $f(z)$ with a Möbius transformation [4]. This would allow us to obtain an analogous result for holomorphic functions $f(z)$ mapping some open circle to another.