kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > [Paper] Watermarks in Stream Processing

[Paper] Watermarks in Stream Processing

29 Dec 2022

In this post we’ll discuss the paper Watermarks in Stream Processing: Semantics and Comparative Analysis of Apache Flink and Google Cloud Dataflow by Akidau et al. [1].

In this paper the authors describe the concept of watermarks, the problem they aim to solve, other alternative mechanisms to watermarks, different implementations by Flink and Dataflow and finally provide experimental results to compare them.

Watermarks

Watermarks are covered in detail in the Chapter 2 of the book Streaming Systems (of which Akidau and Chernyak are also authors) so I’m going to skip the basics here. The paper introduces some mathematical formalism.

A stream system can be seen as a DAG $G$ with a set of notes $V$. Let $T_e$ be the event time domain, $T_p$ the processing time domain and $I$ the set of events that flows through a node $v \in V$. The processing time can be thought of as a function $p: I \rightarrow T_p$ which tags each event with a timestamp when they enter the system, the processing time. Similarly each event it tag with a event time corresponding to when it was created, via a function $e: I \rightarrow T_e$. Events arrive at $v$ sorted by processing time, but not necessarily by event time.

Watermark is a function $w : T_p \rightarrow T_e$ that maps the processing time to event time. When an event $x \in I$ arrives at node $n \in V$, the corresponding watermark is given by $w(p(x))$. The function $w$ must satisfy the following properties:

- Monotonicity: that is, if $t_1 \gt t_2$, then $w(t_1) \ge w(t_2)$

- Conformance: $w(p(x)) \lt e(x), \, \forall x \in I$

- Liveness: $w(t)$ has no upper bound

A conformant watermark is another name for perfect watermark. This property combined with monotonicity says that after processing an event such that the watermark is $y$, it guarantees we’ve processed all elements with event time less than $y$.

To see why, consider an example with events $x_1$ and $x_2$, where $p(x_1) = 5$, $p(x_2) = 6$, $e(x_1) = 4$ and $e(x_2) = 3$. Event $x_1$ will be processed first and has event time 4. In theory the watermark for $p(x_1) = 5$ can be $3$ (satisfies conformance), but then the watermark for $p(x_2) = 6$ must be at least 3 (due to monotonicity), but that is not smaller than $e(x_2) = 3$ and violates the conformance property for $x_2$.

Thus, the watermark function has to know in advance (i.e. be an oracle) when processing $x_1$ that later it will get $x_2$ with a lower event time so it can’t “advance” the watermark greedly. In generally, so heuristics to approximate are used.

I don’t understand what the liveness property is trying to say. The paper later says that $t - w(t)$ is unbounded (i.e. the watermark can be arbitrarily behind the current processing time), but by default functions are already unbounded, so both these conditions seem redundant.

Readiness and Obsolescence

Watermarks allow us to draw a line however imperfect on the progression of event times. This enables two properties known as readiness and obsolescence. To understand them, it’s easier to consider an example.

Suppose we want to compute the count of events from a stream. Since streams are continuous, for this to make any sense we need to define a begining and and end for this count, usually done through a time window with range $(s, e)$.

The idea is that once we’ve processed all events with time greater than $s$, we can emit one event corresponding to the count. However, events are not necessarily ordered so it’s impossible to tell whether we’ve indeed processed all events in that window. That’s where the watermark comes in.

If we treat the watermark as the “judge” or source of truth we can work with an assumption in which we know whether we processed all events with time greater than $s$ by just consulting the current watermark. In other words, the watermark lets us know when we’re ready (hence readiness) to emit the count. Conversely, the watermark lets us know when the data we’ve been used to accumulate the counts is not needed, meaning it’s obsolete (hence obsolescence).

Alternatives

The paper describes two alternatives to watermarks which are more general: timestamp frontiers and punctuations. Timestamp frontiers is a concept introduced by Timely but this paper doesn’t provide much detail besides it working with multiple time domains as opposed to one. I’ll have to read more about Timely to understand better.

Punctuations are a further generalization in that they work with predicates instead of a value. A punctuation is a invariant each operator has that none of the events it will produce will match a given predicate. To implement watermarks via punctuations we could have a predicate saying event_time > watermark, meaning this operator will not produce events with event time higher than its watermark.

The paper claims that both these generalization while more expressive make the system harder to reason about as well as to implement custom user logic, and watermarks are the right balance between simplicity and expressiveness.

Implementation: Flink & Cloud Dataflow

Flink and Cloud Dataflow are similar in many aspects, for example modeling the system as a DAG and providing similar semantics. However, their watermark architecture is different. At a high level, the major difference is that Flink represents watermark as a special type of event along other events [2]. Cloud Dataflow propagates the watermark through pipeline in a separate node.

Propagation

Let’s consider a specific scenario where a given node receives data from two upstream nodes as in Figure 1. In Flink this node will receive the watermark event from each of the upstream nodes. It will compute the minimum of the watermarks and if it’s greater than its internal watermark it will update it, then propagate it was a special event downstream.

In Cloud Dataflow each operator receives the upstream watermarks from a centralized watermark server. It keeps its own watermark locally but periodically it will send it to back to the watermark server which keeps the watermarks for each operator. This centralized server requires additional synchronization mechanisms and RPC calls.

Persistence and Restarts

Flink doesn’t persist the watermarks in any way. When the system restarts, it just recomputes the watermark again. Dataflow on the other hand persists the watermark to disk. This leads to different tradeoffs: Dataflow watermark propagation is slower since it involves RPC calls and disk writes. Flink is slower at restart because it has to recompute the watermarks.

This tradeoff likely stems from how Google datacenters operare. Quoting from [1]:

These design choices were the direct result of environmental assumptions made about where each system would typically be run: Cloud Dataflow’s processing core runs on (…) cluster manager, where priority-driven preemption of running tasks is the norm, whereas Flink jobs were designed for execution on bare metal hardware or public cloud VMs (…), where preemption is non-existent or rare.

Dynamics vs. Static Partitioning

Flink partitioning follows that of the source node, for example if using Kafka as source, the number of workers will be based on partition settings from Kafka and it will be static. Dataflow can change its worker distribution dynamically which computing watermarks more challenging.

Idle workers

Because Flink watermarks are data driven, if one or more workers happens to be idle (due to data skew), it will not emit the special watermark events, so it could cause the pipeline to stall. This scenario has to be handled as a special case by having a node declare itself as idle and have it be ignored by downstream nodes. In Dataflow, since operator emits its watermark periodically to the centralized node, it’s not subject to such problems.

Experiments

The authors setup a specific pipeline for the experiment. First, it has a source that generates events at a constant rate and sets the event time to be the wall-clock time, which means that the events are ordered by their event time. The rationale is to avoid confounding factors due to out of order events.

Then it shuffles the message using 1,000 keys (partitions). Next, for each key, a worker will compute an aggregation using a window of 1-second. This shuffle stage is repeated zero or more times depending on the experiment configuration. Note: the paper says it’s repeated 2 more times, but I think it’s repetition count is a parameter.

For a given window, let $t_w$ be the timestamp when it emitted the output event and $t^{*}_e$ the maximum event time for any event in that window. The watermark latency for that window is defined as $t_w - t^{*}_e$. The system computes this latency for all windows and measures the $p50$ and $p95$.

There are three experiments performed varying the number of workers, throughput (frequency of event generation) and pipeline depth (number of shuffle stages) and seeing the effects on the watermark latency.

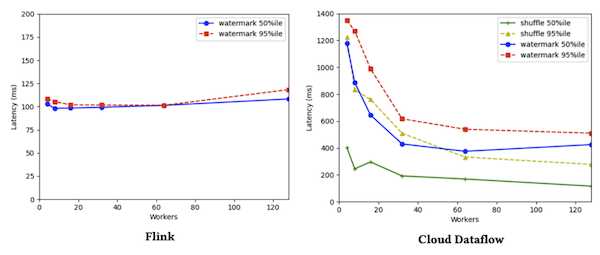

Number Of Workers

For small amount of workers, Flink’s watermark latency is about 10x lower than Dataflow’s. However, as the number of workers increase, Dataflow’s latency goes down while Flink’s stays constant as shown in Figure 1.

Why is the watermark latency higher in Dataflow? The authors argue that a window in Dataflow cannot be closed until the shuffle step process is completed (i.e. the window has to wait even for keys that do not go into it), and as the additional line on the Dataflow’s graph shows, this seems to dominate the watermark latency.

Implicitly, the paper seems to suggest that Flink is not affected by this “synchronization”. As soon as the special watermark event causes the window to close, an event is emitted, regardless on whether the shuffle is completed.

Increasing the number of workers reduces the shuffle latency and thus also the watermark latency. It’s unclear to me what exactly is the bottleneck on the shuffle process though.

This result suggests the centralized watermark server is not a bottleneck, since it is not being scaled with the number of workers.

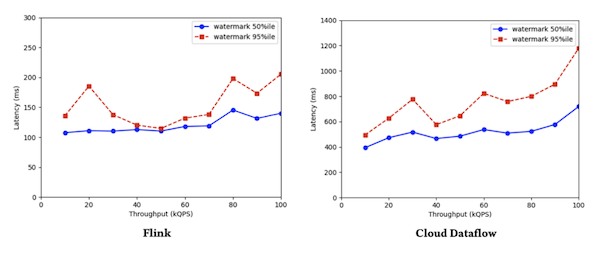

Throughput

When increasing throughput Flink’s watermark latency degrades only slightly while in Dataflow the increase is much higher, as shown in Figure 2. Again, the reason given for the latter is the shuffle.

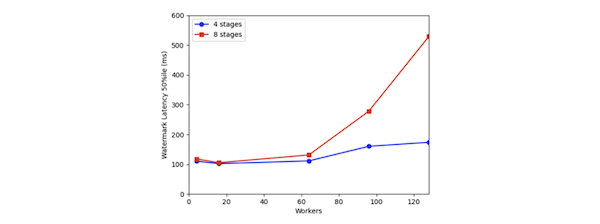

Pipeline Depth

When increasing the number of shuffle stages in Dataflow, no change in watermark latency was observed but it got significanly worse in Flink when the number of stages was set to 8 and the number of workers increased, as shown in Figure 3.

This result is a bit concerning to me. It means that if the “default” experimental setup had used 8 stages as opposed to 4, the first experimental results might have led to a different interpretation. In general there could be other unexplored parameters in the expriment setup that could significantly alter the results, making any comparison between the systems difficult to assess.

Conclusion

In this paper the authors make a case for watermark and provide experimental results to showcase the different tradeoffs between Flink and Cloud Dataflow.

I found that the experiment section could be better. For example, how is shuffle latency defined? Why doesn’t shuffle latency affect Flink? What is the bottleneck in the shuffle latency? Also in section 6.3 the authors hypothesize on the explanation of one of the outcomes but don’t explain why that hypothesis wasn’t or cannot be verified.

On the experiment itself, it seems like the watermark latency is not being affected by the watermark architecture itself, but rather on other parts of the system such as the the shuffle and checkpointing, and these factors don’t seem to be mentioned in Section 5.

Recap

- Why do watermarks make reasoning about out-of-order events simpler? The watermark is monotonic, while event times aren’t.

- What is the main architectural difference between Cloud Dataflow and Flink in regards to watermarks? Dataflow coordinates its watermarks via a centralized node whereas in Flink they are propagated along with events.

Related Posts

[Book] Designing Data Intensive Applications - As noted in this paper, Google’s systems like Cloud Dataflow have to make different tradeoffs compared to open-source distributed systems like Flink because of preemption. This was mentioned in the book Designing Data Intensive Applications as well, albeit in the cotext of batch processing:

The original Map-Reduce framework proposed by Google is “overly” fault tolerant because at Google batch jobs were often preempted in favor of higher priority tasks.