kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > [Paper] Photon

[Paper] Photon

27 Sep 2022

In this post we’ll discuss the paper Photon: Fault-tolerant and Scalable Joining of Continuous Data Streams by Ananthanarayanan et al. [1]. This 2013 paper described the Photon system developed at Google used for associating search queries and ads clicks with low-latency.

This system supports millions of events per second, exactly-once semantics and out-of-order events, with P90 latency less than 7s.

Problem Statement

When a user performs a search query on Google, it displays some ads along the results. When a user clicks on one of such ads, advertisers might want to correlate it with the original query (e.g. what search terms were used).

Logging the search query metadata with the ad click is too expensive, so instead the system only logs an ID associated with the query ID and when needed it joins with the query logs via this ID.

There are two log streams, one representing the search queries and the other the ads clicks. The query has a corresponding query ID and so does the click. Along with the query ID, the streams also store the hostname, process ID and timestamp of the query event, which are needed for imlpementing some operations more efficiently.

Algorithm

I find it instructive to try to solve the problem at a small scale first and have this as a high-level picture of what a more complex system is implementing.

We can basically imagine we’re given a list clicks and a hash table mapping query IDs to queries. Our goal is to find a corresponding query for each click, join them and write to some output.

Due to the out-of-order nature of events, it is possible that when a click is processed by the system the corresponding query hasn’t made to the logs yet (even though the query event has to happen before the click event). Thats why we have a loop to retry a few types. Implicity in wait() is an exponential-backoff.

Two Photon workers execute the same set of events to increase fault-tolerance, but to avoid them joining the same event twice, they coordinate via the id_registry, a hashtable-like id_registry which is used to determine which query_ids have already been joined.

It’s possible that they’re both processing the same click event at the same time while waiting for query so we need to do the id_registry look up inside the loop. We’re omitting more granular concurrency primitives in the code below but for simplicity let’s assume it is thread-safe.

If a query hasn’t been found for a click, the latter is saved in unjoined list for later processing.

for click in clicks:

query_id = click.get_query_id()

click_id = click.get_id()

while max_retries > 0:

if click_id in id_registry:

break

query = queries.get(query_id)

if query:

break

wait()

max_retries -= 1

if query:

event = join(click, query)

if click_id not in id_registry:

id_registry.set(click_id)

write(event)

else:

unjoined.push(click)The algorithm is relatively straightforward but to make sure it can be scaled we need a more complex system. Let’s now take a look at the achitecture.

Architecture

Overview

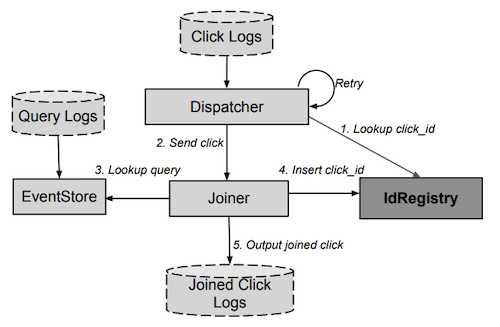

The major components of photon are the IdRegistry, Dispatcher, Joiner and EventStore and are depicted in Figure 1. The dashed components are external to Photon. We’ll go over each of them in detail.

IdRegistry

The IdRegistry implements a distributed hash-table. It consists of servers replicated in multiple geographic regions, each of which stores a copy of the data as a in-memory key-value store.

One of the replicas is elected master. It’s not explicitly said in the paper but I assume writes can only go to the master and the other replicas are eventually made consistent. Master election and eventual consistency are achieved using the Paxos protocol.

Batching. To avoid the overhead of running a Paxos protocol on every write, the IdRegistry batches multiple writes together. One detail to handle is when there are multiple writes to the same click_id in the batch. All writes but the first must report a failure to the requester while the batch is being constructed.

Sharding. To increase throughput of the IdRegistry, Photon uses sharding. Suppose there were $m$ replicas to begin with. Now we scale up each replica to $n$ shards, for a total of $n \cdot m$ servers.

There are $n$ masters to write to, and for each master there are $m-1$ slaves. Each master now handles a subset of the total clicks. More specifically, the $i$-th master handles the clicks such that $\mbox{click_id} \equiv i \pmod n$.

Due to re-scaling, $n$ might change. Suppose a rescaling happens at time $t$. This could happen:

- Before time $t$:

click_idwritten - Time $t$: rescaling, $n$ changes

- After time $t$:

click_idchecked for

In this case we could end up double joining the event, violating the exact-once guarantee.

To avoid this problem in addition to click_id, the IdRegistry also receives the click event time click_time. If $n$ was changed to $n’$ at time $t$, then in theory the hashing logic could be: if $\mbox{click_time} \ge t$, then the shard is calculated using $n’$, otherwise $n$.

The history of changes of $n$ needs to be stored at each IdRegistry and it must be consistent. Due to latency in replication and achieving consistency, it could be that by the time an event with $\mbox{click_time} \ge t$ is processed, the IdRegistry doesn’t have the latest $n$ change, so it would shard the event incorrectly.

To account for that, the rule adds a buffer such that only if $\mbox{click_time} \ge t + \delta_t$ then the shard is calculated using $n’$. The paper [1] gives a different reason for this time buffer - local clock skew - but I failed to see why that matters, since even with clock skew the click_time is fixed given a fixed click_id.

Dispatcher

The dispatcher is responsible for consuming data from the click logs. It consults the IdRegistry to achieve at-most-once semantics and does retries to achieve at-least-once semantics.

It runs several processes in parallel to read from the logs, each of which keeps track of offset for the reads. The list of offsets is shared among all processes and persisted to disk for recovery. It also persists to disk the click events that must be retried.

This means that upon failures it can resume from the point it was before the crash.

Joiner

The joiner receives requests from the dispatcher, containing the click event. It extracts the query_id from it and sends to the EventStore service to look up the corresponding query.

In case the query is not found, the joiner returns a fail response which will cause the dispatcher to retry. The joiner also does throttling: if there are too many inflight requests to the EventStore it returns a fail response.

The joiner then calls an application specific function called adapter which takes the query and click events and returns a new event.

Finally the joiner looks up click_id in the IdRegistry and if none is found, it sets the click_id and writes the event to an output log. If the IdRegistry has the click_id, it simply ignores the event. In either case it returns a success response.

Failure scenarios. The operations of sending a write request to IdRegistry, getting a response and writing the output are not atomic so there are two main failure scenarios.

The IdRegistry might have succesfully written the click_id but its response was lost and not received by the joiner, so the joiner cannot tell if it succeeded. The joiner can then retry the request, but then the IdRegistry needs to know it’s a retry from the same client whose write has already succeeded.

The joiner can send identifying metadata including hostname, process ID and timestamp, which the IdRegistry, a hash table, uses as the value for the key click_id. So if a retry comes where hostname and process ID match an existing entry and the difference between timestamp is small, it will identify it as a retry and accept the write.

Another possibile failure is that the joiner crashes after writing to the IdRegistry but before it writes the output. The paper suggests limiting the inflight requests from a given joiner to the IdRegistry to minimize the blast radius and empirically this happens very infrequently, with 0.0001% of the events.

Recovery. In the second failure case, the system periodically scans the IdRegistry for entries that don’t have a corresponding write to the output. If it finds one, it simply deletes the entry from the IdRegistry and re-queues in the dispatcher for re-processing.

The entries that do have a corresponding write in the output are also periodically removed so reduce the size of the IdRegistry.

EventStore

The EventStore is responsible for returning the data for a query given a query_id. It consists of two parts: CachedEventStore and LogsEventStore.

The CachedEventStore is a in-memory distributed key-value store and serves as cache. It is sharded using consistent hashing, where the hash is based on the query_id.

It implements a LRU cache and is populated by a process that reads the query logs sequentially. The cache is typically able to hold entries for the past few minutes which works for most cases since usually the click and query events are within a short time interval of each other.

One interesting fact is that most of the entries are never read since most of queries don’t have a corresponding ad click, so are never joined.

The cache hit rate based on measurements is between 75-85% depending on traffic. In case of a cache miss, the search falls back to LogsEventStore.

The LogsEventStore is a key-value structure where the key is a composite of process ID, hostname and timestamp. The value is the log filename + offset. A process reads the query logs sequentially and at intervals it writes an entry to the key-value structure. It doesn’t do it for every query to keep the table size contained.

The click event contains the information about the query process ID, hostname and timestamp. It can then send a request and the LogsEventStore will find the entry matching the process ID and hostname and the closest timestamp.

With the log filename and offset, it can perform a seach within the file for the corresponding query ID. Since the entries within a log file are approximately sorted by timestamp, the look up is efficient.

It’s possible to do a tradeoff on the size of the LogsEventStore lookup table and the amount of scan needed by controlling the granularity of the timestamps in the keys.

Experiments

The paper provides several results to demonstrate the non-functional aspects of the system including:

- End-to-end latency: P90 is less than 7 seconds.

CachedEventStorehit rate: between 75-85%.- Resilience over one data center failure.

- Performance of batching on

IdRegistry: QPS is 6-12 for batched vs 200-350 for unbatched. - Auto-balancing of load upon resharding

- Duplication of work: less than 5% of events processed by two processors.

Conclusion

Photon is described as a system to solve a very specific problem: joining queries with ad clicks. It can be generalized to other applications as hinted by the adapter function.

It does however implement a very specific type of join which I’ve seen being called a quick join: it assumes an event from the main stream (clicks) is joined exactly once. In some other types of joins an event might be joined zero or multiple times as well.

I was initially thinking that the IdRegistry could use consitent hashing to avoid issues with re-sharding but it doesn’t work. IdRegistry is not a best-effort system like a cache and thus can’t affort cache misses, so any re-sharding needs to be “back compatible” which makes it a lot more complicated.

I liked the level of technical details described to address uncommon issues like events being dropped due to failures.

I found interesting that Photo has two workers working on the exact same shards in parallel for fault-tolerance. I don’t recall having seen this design before.

Related Posts

- [Book] Streaming Systems - Chapter 9 talks about streaming joins more generally in less detail.

- Consistent Hashing - discusses consistent hashing which is utilized by Photon.

- The Paxos Protocol - discusses the Paxos prototol which Photon utilizes indirectly via PaxosDB.

- [Paper] Spanner - discusses the

TrueTimeAPI which is leveraged by Photon to bound clock drift across the hosts.

References

- [1] Photon: Fault-tolerant and Scalable Joining of Continuous Data Streams - Ananthanarayanan et al.