kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Consistent Hashing

Consistent Hashing

12 Apr 2019

Daniel Lewin was an Israeli-American mathematician and entrepreneur. He was aboard the American Airlines Flight 11, which was hijacked by al-Qaeda during the September 11 attacks.

Tom Leighton is a professor (on leave) of Applied Mathematics at CSAIL @ MIT and an expert on algorithms for network applications.

Together, Lewin and Leighton founded the company Akamai, which was a pioneer in the business of content delivery networks (CDNs) and is currently one of the top players in the segment. One of the key technologies employed by the company was the use of consistent hashing, which we’ll present in this post.

Motivation

One of the main purposes of the CDN is to be a cache for static data. Due to large amounts of data, we cannot possibly store the cache in a single machine. Instead we’ll have many servers each of which will be responsible for storing a portion of the data.

We can see this as a distributed key-value store, and we have two main operations: read and write. For the write part, we provide the data to be written and an associated key (address). For the read part, we provide the key and the system either returns the stored data or decides it doesn’t exist.

In scenarios where we cannot make any assumptions over the pattern of data and keys, we can try to distribute the entries uniformly over the set of servers. One simple way to do this is to hash the keys and get the remainder of the division by N (mod N), where N corresponds to the number of servers. Then we assign the entry (key, value) to the corresponding server.

The problem arises when the set of servers changes very frequently. This can happen in practice, for example, if servers fail and need to be put offline, or we might need to reintroduce servers after reboots or even add new servers for scaling.

Changing the value of N would cause almost complete redistribution of the keys to different servers which is very inefficient. We need to devise a way to hash the keys in a way that adding or removing servers will only require few keys from changing servers.

Consistent Hashing

The key idea of the consistent hashing algorithm is to include the key for the server in the hash table. A possible key for the server could be its IP address.

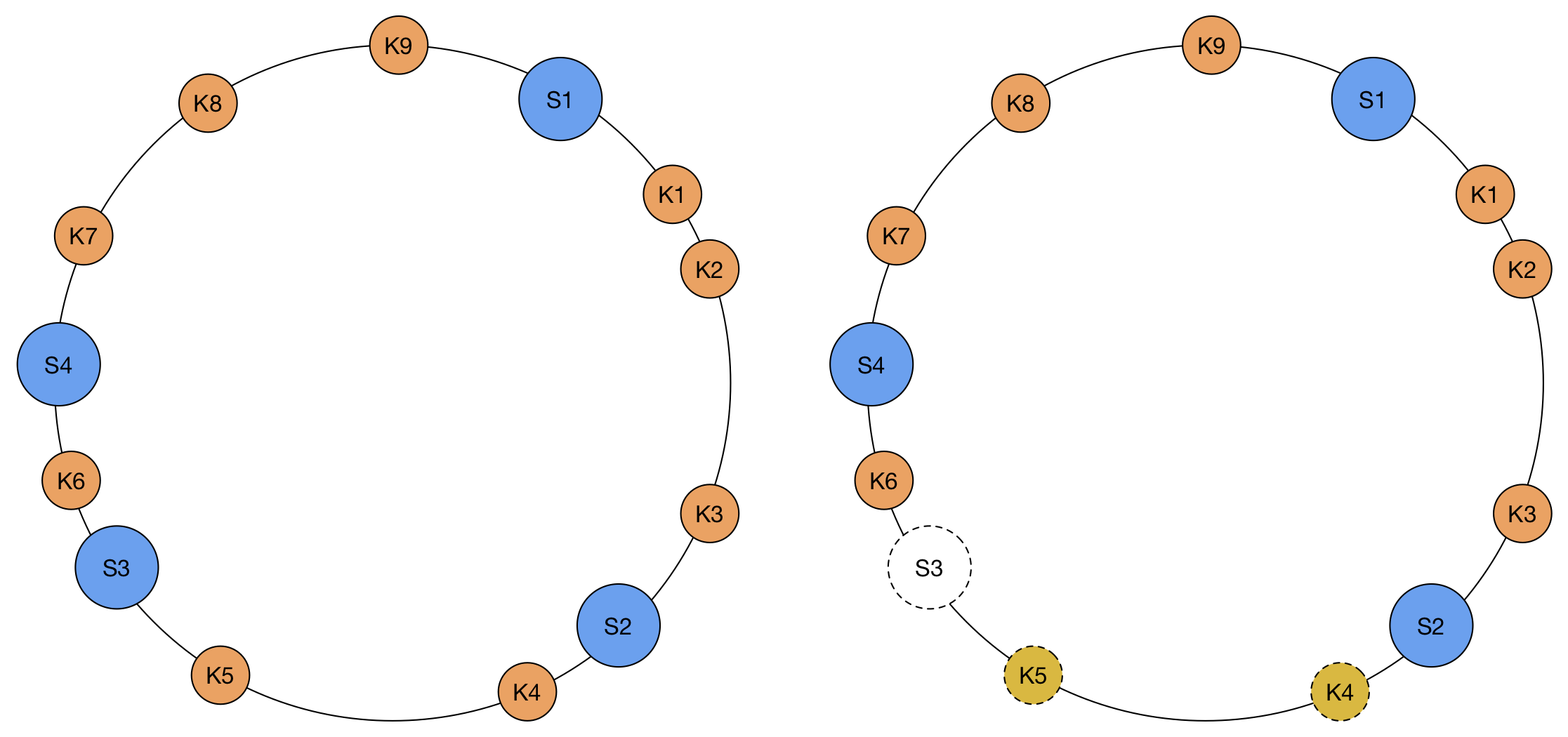

Say that our hash function h() generates a 32-bit integer. Then, to determine to which server we will send a key k, we find the server s whose hash h(s) is the smallest that is larger than h(k). To make the process simpler, we assume the table is circular, which means that if we cannot find a server with hash larger than h(k), we wrap around and start looking from the beginning of the array.

If we assume that the hash distributes the keys uniformly, including the server keys, we’ll still get a uniform distribution of keys to each server.

The advantage comes to when adding and removing servers to the list. When adding a new server sx to the system, its hash will be in between 2 server hashes, say h(s1) and h(s2) in the circle. Only the keys from h(s1) to h(sx), which belonged to s2, will change servers, to sx. Conversely, when removing a server sx, only the keys assigned to it will need to go to a different server, in this case the server that immediately follows sx.

How can we find the server associated to a given key? The naive way is to scan linearly the hashes until we find a server hash. A more efficient way is to keep the server hashes in a binary balanced search tree, so we can find the leaf with the smallest value larger that h(x) in O(log n), while adding and removing servers to the tree is also a O(log n) operation.

Implementation in Rust

We will provide an implementation of the ideas above in Rust as an exercise. We define the interface of our structure as

pub struct ConsistentHashTable {

containers: rbtree::RBTree<u32, Entry>,

entries: HashSet<u32>,

// The hash function must have the property of mapping strings to

// the space of u32 numbers with uniform probability.

hash_function: fn (&String) -> u32

}Note that we’ll store the list of servers (containers) and keys (entries) in separate structures. We can store the entries in a simple hash table since we just need efficient insertion, deletion and look up. For the containers we need insertion, deletion but also finding the smallest element that is larger than a given value, which we’ll call successor. As we discussed above, we can use a binary balanced search tree which allow all these operations in O(log n), for example a Red-Black tree. I found this Rust implementation of the Red-Black tree [1].

Finally, we also include the hash function as part of the structure in case we want customize the implementation (handy for testing), but we can provide a default implementation.

To “construct” a new structure, we define a method new() in the implementation section, and use farmhash as the default implementation for the hash function [2].

impl ConsistentHashTable {

pub fn new() -> ConsistentHashTable {

return ConsistentHashTable {

containers: rbtree::RBTree::new(),

entries: HashSet::new(),

hash_function: hash_function,

};

}

...

}

fn hash_function(value: &String) -> u32 {

return farmhash::hash32(&value.as_bytes());

}The insertion and removal are already provided by the data structures, and are trivial to extend to ours. The interesting method is determining the server corresponding to a given key, namely get_container_id_for_entry().

In there we need to traverse the Red-Black tree to find the successor of our value v. The API of the Red-Black tree doesn’t have such method, only one to search for the exact key. However due to the nature of binary search trees, we can guarantee that the smallest element greater than the searched value v will be visited while searching for v.

Thus, we can modify the search algorithm to include a visitor, that is, a callback that is called whenever a node is visited during the search. In the code below we start with a reference to the root, temp, and in a loop we keep traversing the tree depending on comparison between the key and the value at the current node.

fn find_node_with_visitor<F>(

&self,

k: &K,

mut visitor: F

) -> NodePtr<K, V> where F: FnMut(&K) {

if self.root.is_null() {

return NodePtr::null();

}

let mut temp = &self.root;

unsafe {

loop {

let key = &(*temp.0).key;

let next = match k.cmp(key) {

Ordering::Less => &mut (*temp.0).left,

Ordering::Greater => &mut (*temp.0).right,

Ordering::Equal => {

visitor(&key);

return *temp;

}

};

visitor(&key);

if next.is_null() {

break;

}

temp = next;

}

}

NodePtr::null()

}Let’s take a detour to study the Rust code a bit. First, we see the unsafe block [3]. It can be used to de-reference a raw pointer. A raw pointer is similar to a C pointer, i.e. it points to a specific memory address. When we de-reference the pointer, we have access to the value stored in that memory address. For example:

let mut num = 5;

let r1 = &num as *const i32;

unsafe {

println!("r1 is: {}", *r1);

}The reason we need the unsafe block in our implementation is that self.root is a raw pointer to RBTreeNode, as we can see in line 1 and 4 below:

struct NodePtr<K: Ord, V>(*mut RBTreeNode<K, V>);

...

pub struct RBTree<K: Ord, V> {

root: NodePtr<K, V>,

...

}

...

// in find_node_with_visitor()

let mut temp = &self.root;

let key = &(*temp.0).key;The other part worth mentioning is the type of the visitor function. It’s defined as

fn find_node_with_visitor<F>(

...

k: &K,

mut visitor: F

) -> where F: FnMut(&K) {

...

visitor(&key);

...

}It relies on several concepts from Rust, including Traits, Closures, and Trait Bounds [4, 5]. The syntax indicates that the type of visitor must be FnMut(&K), which in turns mean a closure that has a single parameter of type &K (K is the type of the key of the RB tree). There are three traits a closure can implement: Fn, FnMut and FnOnce. FnMut allows closures that can capture and mutate variables in their environment (see Capturing the Environment with Closures). We need this because our visitor will update a variable defined outside of the closure as we’ll see next.

We are now done with our detour into the Rust features realm, so we can analyze the closure we pass as visitor. It’s a simple idea: whenever we visit a node, we check if it’s greater than our searched value and if it’s smaller than the one we found so far. It’s worth noticing we define closest_key outside of the closure but mutate it inside it:

let mut closest_key: u32 = std::u32::MAX;

self.containers.get_with_visitor(

&target_key,

|node_key| {

if (

distance(closest_key, target_key) >

distance(*node_key, target_key) &&

*node_key > target_key

) {

closest_key = *node_key;

}

}

);We also need to handle a corner case which is that if the hash of the value is larger than all of those of the containers, in which case we wrap around our virtual circular table and return the container with smallest hash:

// Every container key is smaller than the target_key. In this case we 'wrap around' the

// table and select the first element.

if (closest_key == std::u32::MAX) {

let result = self.containers.get_first();

match result {

None => {

return Err("Did not find first entry.");

}

Some((_, entry)) => {

let container_id = &entry.id;

return Ok(container_id);

}

}

}The full implementation is on Github and it also contains a set of basic unit tests.

Conclusion

The idea of a consistent hash is very clever. It relies on the fact that binary search trees can be used to search not only exact values (those stored in the nodes) but also the closest value to a given query.

In a sense, this use of binary trees is analogous to a common use of quad-trees, which is to subdivide the 2d space into regions. In our case we’re subdividing the 1d line into segments, or more precisely, we’re subdividing a 1d circumference into segments, since our line wraps around.

I struggled quite a bit with the Rust strict typing, especially around passing lambda functions as arguments and also setting up the testing. I found the mocking capability from the Rust toolchain lacking, and decided to work with dependency injection to mock the hash function and easier to test. I did learn a ton, though!

References

- [1] GitHub: /tickbh/rbtree-rs

- [2] GitHub: seiflotfy/rust-farmhash

- [3] The Rust Programming Language book - Ch19: Unsafe Rust

- [4] The Rust Programming Language book - Ch13: Closures: Anonymous Functions that Can Capture Their Environment

- [5] The Rust Programming Language book - Ch13: Traits: Defining Shared Behavior