kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > A Puzzling Election

A Puzzling Election

06 Nov 2020

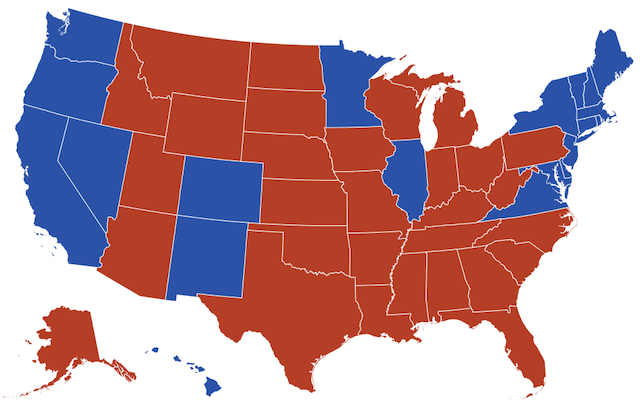

In 2016, Donald Trump won the US presidential election. He won with 304 electoral votes over Hillary Clinton with 227 votes, even though Clinton had almost 3 million more popular votes than Trump.

This is due to how the US decides to count votes. In its system each state is given a number of votes equal to the number of representatives (proportional to the state population) plus senators (2 per state). There are a total of 435 representatives and 100 senators and the District of Columbia (DC) gets 3 votes (proportional to its population, but no more votes than the least populated state, Wyoming), for a total of 538 electoral votes. A candidate wins the election if they get more than half of the electoral votes, that is, at least 270.

All but two states (Maine and Nebraska) have an all-or-nothing system, which means that whoever wins the majority of the popular votes in that state, gets all the electoral votes. For example, California has 55 electoral votes where Clinton got 8,753,788 (61.73%) of votes and hence the 55 electoral votes and Trump none. Had she received 100% the votes, she would have received the exact same electoral votes.

This all-or-nothing system is the source of the counter-intuitive result in which a candidate with the majority of the popular vote might not win the election. This led me to wonder about the extreme case: What would be the most popular votes a candidate can get without winning?

In this post we explore this problem.

Problem Formulation

To simplify the problem a bit, let’s assume all states including Maine and Nebraska use an all-nothing system. Let’s also assume the number of popular votes per state is the same as the 2016 election, but we can choose who it went for.

We’ll further assume that there are only two candidates, A and B, and a vote has to go to either of them. What is the minimum number of popular votes A needs to win?

Ballpark estimate

If we assume there are sets of states that divide the electoral votes into roughly two equal parts, then candidate A needs to win ~50% of the electoral votes.

Also, since the number of electoral votes is roughly proportional to the population and assuming the voting participation rate is roughly the same across the states, candidate A needs to win ~50% of the votes of a set of states that add up to ~50% of the electoral votes. This is ~25% of the total votes for A and ~75% for B, so we’d expect the exact results we’ll compute to be around this ratio.

The Inverse Knapsack Problem

Let $S^*$ the set of states A won in an optimal solution. If a state $i$ is in $S^*$, A needs exactly the minimum majority of votes, so if there were $v_i$ votes, we need $\lfloor v_i/2 \rfloor + 1$ votes. If a state is not in $S^*$, there’s no reason to spend any votes there, so it should be 0.

Given these observations, we can model this problem as picking a set of items corresponding to the states and DC, with weights equal to their electoral votes and costs equal to the minimum majority of popular votes.

Picking a state corresponds to candidate A winning that state. We want to pick a set of items that minimizes the total cost (number of popular votes) but has total weight greater or equal 270 (the minimum majority of the electoral votes).

More generally, let $S$ be a set of items, where item $i \in S$ has cost $c_i$ and weight $w_i$. The problem can be formulated as an integer linear programming if we introduce $x_i \in {0, 1}$ where $x_i = 1$ corresponds to picking that item.

\[\min \sum_{i \in S} x_i c_i\]Subject to

\[\sum_{i \in S} x_i w_i \ge W\]We’ll call this the Inverse Knapsack Problem. To recall, the Knapsack Problem consist of maximizing the value of a set of items with total weight not exceeding $W$, which can be modelled as integer linear programming:

\[\max \sum_{i \in S} x_i c_i\]Subject to

\[\sum_{i \in S} x_i w_i \le W\]The Inverse Knapsack Problem is NP-Complete

The decision version of the knapsack problem can be defined as:

($D_1$) Is there any solution with total value of at least $C_1$ weighing no more than $W_1$?

In general this is an NP-complete problem. The decision version of the inverse knapsack problem can be defined as:

($D_2$) Is there any solution with total cost of at most $C_2$ weighing no less than $W_2$?

If we can reduce the knapsack problem to the inverse knapsack problem, we prove that the later is also an NP-complete problem.

Consider an instance of $D_1$ with $C_1$ and $W_1$.

Let $X$ denote a subset of $S$ and $c(X)$ and $w(X)$ the total value and weight of the items in $X$, respectively. Let $C_T$ be the sum of values of all items, i.e. $C_T = c(S)$. Let $W_T$ be the sum of weights of all items, i.e. $W_T = w(S)$.

We create an instance of $D_2$ with $C_2 = C_T - C_1$ and $W_2 = W_T - W_1$.

Suppose $D_1$ is true. Then there’s a set of items $X^*$ such that $c(X^*) \ge C_1$ and $w(X^*) \le W_1$. Let $Y^*$ be the set of items not in $X^*$ (i.e. $S \setminus X^*$).

Their weight is $w(Y^*) = W_T - w(X^*)$, and since $w(X^*) \le W_1$, $w(Y^*) = W_T - w(X^*) \ge W_T - W_1 = W_2$. Similarly we can see that $c(Y^*) \le C_2$, which means $Y^*$ is a solution to $D_2$.

This implies tht if $D_1$ has a solution, then $D_2$ has one too. We can use a symmetric argument to show that if $D_2$ has a solution, then $D_1$ has too. This constructive proof that shows we can reduce the decision version of the knapsack problem into the inverse knapsack problem.

While this problem is NP-complete, for many real-world instances it can be solved exactly via dynamic programming as we’ll see next.

Dynamic Programming

The reduction from the decision version of the knapsack problem into the inverse knapsack problem can also be used to reduce the optimization version of the inverse knapsack problem (let’s call it $O_2$) into the knapsack problem ($O_1$).

Let $Y^*$ be the optimal solution for $O_2$ with $W_2$. We create an instance of $O_1$ with $W_1 = W_T - W_2$, and $X^* = S \setminus Y^*$. Since $Y^*$ is a feasible solution, $w(Y^*) \ge W_2$ and we can show that $w(X^*) \le W_1$, so $X^*$ is a feasible solution to $O_1$.

We now claim $X^*$ is the optimal solution for $O_1$. Suppose it’s not. Then there is $\hat{X}$ such that $c(\hat{X}) > c(X^*)$ and $\hat{Y} = S \setminus \hat{X}$. Since $c(X^*) = C_T - c(Y^*)$ and $c(\hat{X}) = C_T - c(\hat{Y})$ we get $C_T - c(\hat{Y}) > C_T - c(Y^*)$, which means $c(\hat{Y}) < c(Y^*)$, which is a contradiction.

Hence we can solve the original problem by creating $O_1$ with $W = 538 - 270 = 268$, solve the knapsack problem and reverse our picks. We can solve the knapsack problem in $O(nW)$ using dynamic programming, where $n$ would be the number of states + DC, 51.

Implementation

He’s a Python implementation that uses a $O(nW)$ matrix ks, where ks[i][w] represents the best possible knapsack value using only the first i-1 items and with size w.

We can use ks to retrieve the elements used in the optimal solution.

def solve_knapsack(items, W):

# Empty set

k = [-1]*(W + 1)

k[0] = 0

ks = [k]

for item in items:

next_k = k.copy()

for w in range(len(k)):

next_w = w + item['w']

if next_w > W:

break

if k[w] < 0:

continue

next_c = k[w] + item['c']

if k[next_w] == -1 or k[next_w] < next_c:

next_k[next_w] = next_c

k = next_k

ks.append(k)

# Find the best size

max_w = W

while ks[-1][max_w] == -1:

max_w -= 1

# Backtrack to find which items were used

picked = []

curr_w = max_w

for idx in reversed(range(len(ks))):

if ks[idx][curr_w] > ks[idx - 1][curr_w]:

picked.append(idx - 1)

curr_w -= items[idx - 1]['w']

return pickedWe can reduce the inverse knapsack problem to the knapsack problem by the procedure we described above ($W_1 = W_T - W_2$) and then get the complement of the items:

def solve_inverse_knapsack(items, W):

total_weight = sum([item['w'] for item in items])

solution = solve_knapsack(items, total_weight - W)

solution_lookup = set(solution)

# the complement of items in solution

return [i for i in range(len(items)) if i not in solution_lookup]The full source is on Github.

Results

We obtained the following optimal number of popular votes:

| A (winner) | B | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 29,152,906 | 10,7516,331 | 136,669,237 |

| 21.3% | 78.6% | 100% |

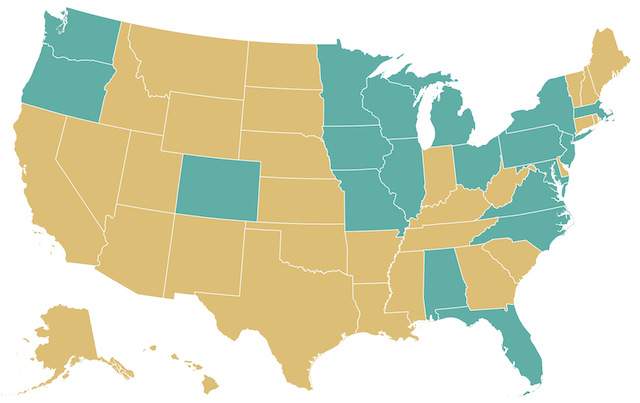

We also generate the map with the states where A gets $\lfloor v/2 \rfloor + 1$ votes in gold and 0 votes in green:

Analysis

It’s theoretically possible for a candidate to win the US election (with the caveat of the Maine-Nebraska simplification) by wining only 21.3% of the popular votes. This ratio is not too far from our ballpark estimate of 25%.

While populous states yield a lot of electoral votes, it also requires a lot of popular votes to be won, so it doesn’t matter too much in finding the optimal solution. A better heuristic are picking states with low voter turnout (like Texas, ~50%), since it requires a smaller subset of the population to win, but it still yields electoral votes that are proportional to the full population.

If we didn’t fix the number of votes per state, the problem would be less interesting, because A would just need one vote to win a state (and B would get 0), whereas where A lost, we’d assume there was 100% turnout and B got all the votes. Candidate A would need just 12 popular votes to win, by picking the top states by electoral votes!

Conclusion

It’s election time and was interesting to be able to model a real world example as a combinatorial optimization problem. I didn’t recall the inverse knapsack problem, though it’s likely I’ve seen it in some form before.

I had forgotten how to retrieve the items of the knapsack using dynamic programming, and was only able to come up with a $O(nW)$-memory solution. Is it possible to do it using $O(W)$ memory?

This post was a good way for me to learn how the voting system works in the US. I’ve recently read The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, and learned how there needed to be compromises to make the Constitution pass, which left a lot of power to states. This can be seen in the fact that the number of senators is proportional to the number of states (not population) and also the electoral votes, in which 48 states treat them as a unit.

Related Posts

- US as an hexagonal map describes an alternative way that represents US states in a uniform way, since the geographical representation puts too much emphasis in large states like Alaska. A similar issue exists with electoral votes where states like New York feels underrepresented even though it was a large number of votes. There are alternative representation as well, like here.

- Shortest String From Removing Doubles is another puzzle in which we use backtracking to recover the solution from an auxiliary array. I don’t know if the solution can be classified as dynamic programming because it doesn’t build open smaller instances of the problem explicitly.

References

[1] Wikipedia - 2016 United States presidential election