kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Shortest String From Removing Doubles

Shortest String From Removing Doubles

25 May 2020

I recently ran into this interesting programming puzzle: given a string S, find the shortest string that can be obtained by repeatedly removing any two consecutive characters which are the same.

For example abcdeefgh can be reduced to abcdfgh by erasing the ee. Some other examples:

abbbc -> abcaaaa -> aa -> (empty string)abba -> aa -> (empty string)abcddcbe -> abccbe -> abbe -> ae

We will call a pair of consecutive characters that are the same a double.

The first idea that came to mind is to use a greedy algorithm removing the first double we find and repeat for the resulting string. This turns out to be the optimal solution but it isn’t obvious to me why.

Isn’t there a particular example where the order in which we remove doubles might yield a shorter resulting string? We now provide a sketch of a proof on the optimality.

Theorem. Always removing the first double from the string will yield the shortest string possible.

Proof. Suppose there is an optimal order of removing doubles p1, p2, p3, …, pn. Suppose the first double is at position (i, i+1). By our choice of i, we can see that until (i, i+1) is removed, there are no doubles to the “left” of it.

We claim that the double (i, i+1) will always be removed. The only case this would not be true is if we have a triplet (i, i+1, i+2) with the same character and we choose to remove the (i+1, i+2) double instead, but we can see that the resulting string would be the same if we removed (i, i+1), so our claim can be made true without loss of generality. Let’s assume then (i, i+1) is removed in the k-th iteration of the optimal solution, so pk=(i, i+1).

Because (i, i+1) is the first double, all removals in the optimal solution before removing pk=(i, i+1) happen strictly to the “right” of it, and all this time (i, i+1) is a choice. Conversely removing (i, i+1) doesn’t affect the doubles available for removal up to when (i, i+1) would be removed. Thus if the first k removals in an optimal sequence is given p1, p2, p3, …, pk=(i, i+1), we can reorder this to pk, p1, p2, … pk-1 and the resulting string will be the same. QED.

Using this, we can now solve this problem using Python recursively:

def remove_doubles(s):

if s == '':

return ''

for i in range(len(s) - 1):

if s[i] == s[i + 1]:

return remove_doubles(s[:i] + s[i + 2:])

return sThis solution is O(n^2), but can we do it in O(n)? There are two things we can try: one is to remember the position of the last double removed so we don’t have to start over searching for the next double and the other is to not generate a new string but update the character locally.

Remembering the position. When removing the first double (i, i+1), we know the next first double in the resulting string will be either in (j, j+1) for j >= i+2 or (i-1, i+2). The latter is true because for (k, k+1), k <= i-2 was not a double before and none of these pairs changed, hence the only double that could have been created is (i-1, i+2). Thus we need only to check for (i-1, i+2) before moving on.

Constant time removal. Strings are a list of characters, so removing characters require O(n) time in the worst case. A more suitable data structure for this operation is a doubly-linked list, which allows us perform all the operations describe above in O(1), including removing doubles.

In this particular case, since we don’t need to insert new elements, we can use a hybrid approach by using an additional array for the pointers, prev (representing the linked list pointers). Instead of removing an element of an array, which is expensive, we simply update the pointers such that it looks like they were removed.

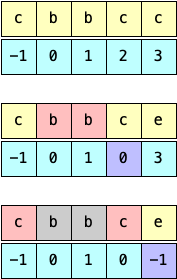

More concretely, the pointer at position p points to the first non-removed element to its left. If there are no elements to the left, we use -1 as sentinel. We initialize the pointers at each position so that it points to the previous element, that is, prev[i] = i - 1.

We then iterate over the characters of the string. At any given iteration there are two cases we need to consider: when the new pair is ahead (e.g. aa) and when the new pair shows up because deleting a previous pair made them adjacent (e.g. abba after deleting bb).

Case 1. When we remove a pair of adjacent indexes such as (i, i+1), we need to make the next index, i+2 point to the previous index. However, the index prior to i might have been removed. The source of truth of the previous element is in prev[i], so we have prev[i + 2] = prev[i].

Case 2. In our solution we might need to remove non-adjacent elements. For example in abba. We first remove bb, leaving us with a--a. The a’s are not adjacent in the original array, but they’re in regards to prev, such that s[3] = s[prev[3]] = s[0]. In general terms, we can check if s[i] = s[prev[i]]. Removing them requires updating the pointer of the next element prev[i+1] = prev[prev[i]].

Going back to Case 1, we note that (i, i+1) can be seen as (prev[i], i), in case both Case 1 and Case 2 can be neatly implemented via:

prev[i] >= 0 and s[i] == s[prev[i]]:

prev[i + 1] = prev[prev[i]]We can finally reconstruct the remaining string, if any, by backtracking on prev:

i = prev[len(s)]

r = ''

while i != -1:

r += s[i]

i = prev[i]It’s worth noting that prev is only correct for indices that were not deleted themselves. Consider the example: abccddba. When we remove cc, index 4 now points to index 1. However, once dd is removed, then bb, index 4 is incorrect, but that’s fine because it was deleted with dd. Also worth noting that the resulting string r is reversed.

The full code is given:

def remove_doubles(s):

# Points to the first non-empty position to the left

# Add a sentinel at the end

prev = list(range(-1, len(s)))

for i in range(len(s)):

if prev[i] >= 0 and s[i] == s[prev[i]]:

prev[i + 1] = prev[prev[i]]

i = prev[-1]

r = ''

while i != -1:

r += s[i]

i = prev[i]

# Reverse

return r[::-1]Complexity. The first loop is clearly linear and if we notice that p[i] < i, we can see the second loop is also linear.

Conclusion

This was an nice problem because while the greedy solution works, understanding why requires more thought.

The code challenge has only small strings, so an O(n^2) passes easily. But by introducing the artificial constraint that the code must run in O(n), we made the problem more challenging and interesting.

My initial solution handled Case 1 and Case 2 separately and had a bunch of corner-case checks and off-by-one adjustments. I spent extra time to clean it up and was really pleased to come up with a much shorter solution!