kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Negative Bloom Filters

Negative Bloom Filters

22 Jun 2024

Recently at work we were trying to solve a performance bottleneck. A part of the system was making requests to a remote key-value store but we saw that the majority of the requests resulted in the key not existing in the store.

An idea was to implement a negative cache: locally store the keys for which no value exist, to prevent unnecessary future requests. It should not use much memory and false negatives are fine (would result in redundancy), but false positives are not allowed (would result in incorrect results).

This seems like a problem we can solve with a variant of the classic Bloom filter, but with different guarantees of false negatives and positives, so I did some investigation and summarized in this post.

Recap: Bloom Filters

A Bloom filter [1] is a data structure that implements a set. In the most basic form, it allows efficient insertion and membership query. It’s also very space-efficient. The drawback however is that the membership query is not 100% accurate: If it says an element is not in the set, then it’s definitely not there. However, if it says an element is in the set, there’s some probability the element is actually not there.

We studied Bloom filters in detail in a previous post. Summarizing, the data structure itself is a simple bit array of size $m$. Whenever we want to insert a element in the set, we hash it using $k$ hash functions, obtaining $k$ indices on the bit array which we set.

To check if a element is in the set, we again hash it using the same $k$ hash functions, obtaining $k$ indices on the bit array and return true only if all the bits are set. The intuition is that different elements might collide on the same hash but the chances of them colliding on $k$ hashes is much smaller. However, as the bit array fills up, the chance of collisions with a set of different elements goes up.

In that post, we concluded that the probability of false negatives is 0, and the probability of false positives is $p = 0.62^{m/n}$, where $n$ is the number of elements inserted, with the optimal choice of $k = \ln(2)m/n$.

The complexity of insertion and removal is $O(k)$, but $k$ is usually a small constant. Space complexity is $O(m)$ bits.

Negative Bloom Filter

Now suppose we want a data structure like a Bloom filter but it has the opposite guarantees: If it says an element is in the set, then it’s definitely there. However, if it says an element is not in the set, there’s some probability the element is actually there.

All references I found suggest it’s not possible, but I haven’t been able to find a formal proof for this. One difficulty is that the problem is not well defined: what are the constraints of this data structure? Does it also have to use $O(m)$ bits and have the accuracy for the false negative be $p = 0.62^{m/n}$?

A Zero-element Filter

If we don’t have any guarantees on the probability, a simple way to satisfy the constraint is to always say the element is not in the set. We don’t have to store any elements, and it never reports false positives this way!

How about false negatives? Let $N$ be the number of elements on the domain (possibly infinite) and that the element we’re querying is selected at random from this domain. If there are $n$ elements currently in the set, then the probability of a random element being in the set is $n/N$, which is also the probability of false negative. If $N$ is much larger than $n$, that number is actually quite low.

In practice however, the elements queried are not uniformily distributed. In fact it’s very likely that an element shows up repeatedly, so the false negatives would be pretty high.

A One-element Filter

Let’s now add the constraint that for at least one element that exists in the set, it must correctly report it is in there.

The counterpart property in the regular Bloom filter is that for at least one element that doesn’t exist in the set, it must report so. If the filter is not nearly or completely full and the hash function is decent, this shall be safisfiable.

For the inverse case, let’s be lenient and say that it only has report the presence in the set for exactly one element $s$.

To know whether $s$ is in the set, we need to store something that identifies it in our data structure. We can store $s$ itself, but it might be larger than $m$ bits in size! So perhaps we can hash it and bring its size down to $m$ bits. But as long as $N$ (the size of the domain) is larger than $2^m$, by the pigeonhole principle there are other strings that will hash to the same value, i.e. collisions are unavoidable.

Let $s’$ be an element which hashes to the same value as $s$ and suppose $s’$ is not in the set. So when we query for $s’$, the structure won’t be able to tell it apart from $s$ and falsely report it is in the set, and we violated the 0 probability of false positives.

A Special Hash Table

So even a minimally useful negative Bloom filter is not possible. What can we do? A middleground is presented in [2]. The idea is that we use a regular hash table, except that:

- When we get a collision we replace the entry instead of keeping multiple entries

- We store part of the hash element as value.

Let’s cover it in more details. Let $l$ be an integer such that $m = 2^{l}$ and we construct an array of size $m$ with each element being of size $b$ (bits). We then choose a hash function that hashes a given element to at least $b + l$ bits.

To insert a element, we hash it and use the first $l$ bits as the index in the array, and the remaining $b$ bits as the value in that array. To check for membership, we repeat the process to find the index, but only claim the item is in the array if the remaining $b$ bits match what’s stored.

It’s a very simple process and yet it yields good practical gurantees:

Proposition 1. The probability of a false positive is less than $1/2^{b}$.

Now, assuming a completely random hash function, that position can be filled with any of the $2^b$ values with equal probability, so the chance of it being exactly $v$ is $1/2^b$.

If the number of elements inserted so far is small, there's also a chance that position $p$ hasn't even been set yet, but here we consider the worst case scenario.

Note that this probability doesn’t depend on how many elements have been inserted so far.

Proposition 2. The probability of a false negative is less than $n/2^{l}$, where $n$ is the number of elements inserted.

The algorithm computed a index $p$ and value $v$ for that element when inserting it. For any given element to replace it, it must match on $p$ and mismatch on $v$. The probability on mismatching on $v$ is very high, so we can simplify and assume the probability of replacement is $1/2^{l}$.

Let $n$ be the number of elements inserted after our element in question was inserted. For its value to not be replaced, we must have every single one of these entries to not be $p$, which has probability $(1 - 1/2^{l})^n$. Thus the probability of it being replaced is $1 - (1 - 1/2^{l})^n$.

For large values of $l$, $1 - 2^{-l} \approx \exp(-2^{-l})$, so the probability is $1 - \exp(-n2^{-l})$. Using that $1 - e^{-x} \lt x$, we conclude that $$Pr \lt n2^{-l}$$

In [2], the probability of a false positive is claimed to be $1/2^{p + b}$. This would be true if we stored the entire hash as value, but we only store $b$ bits of it. The other $p$ bits are used deterministically as the index in the array. However, this doesn’t change the conclusion.

Inserting and querying for a element are $O(1)$ operations. The space used by this structure is $O(2^l b)$ bits. In [2] Ilmari Karonen suggests $l = 16$ and $b = 128$, which corresponds to 1MB of memory, with a false positive rate of $1/2^{128}$ which is for most practical purposes indistinguishable from 0. The false negative rate will depend on how many elements are inserted.

This is a type of LRU cache, except that we don’t store the value and the key size is bounded by $O(b)$ bits.

Implementation

Here’s a simple implementation in Python. For lack of better ideas, I’ll call it ApproxSet:

import hashlib

class ApproxSet:

def __init__(self, b=128, l=16):

self.b = b

self.arr = [None] * (2**l)

def _get_hash_pair(self, value):

# 256-bit hash in hexadecimal

hash_hex = hashlib.sha256(str(value).encode()).hexdigest()

hash_int = int(hash_hex, 16)

# Use first l bits for index

index = (hash_int >> self.b) % len(self.arr)

# Use last b bits for value

value = hash_int & ((1 << self.b) - 1)

return (index, value)

def add(self, value):

(index, value) = self._get_hash_pair(value)

self.arr[index] = value

def __contains__(self, value):

(index, value) = self._get_hash_pair(value)

return self.arr[index] == valueAs we can see, the implementation is very simple, except for getting the index and value from the hash.

Experimentation

The setup is that we insert N random elements (sample from a domain of size M) into this data structure and when it reaches a multiple of 10 in percentage of occupancy, we query another N random elements to compute the probabilities.

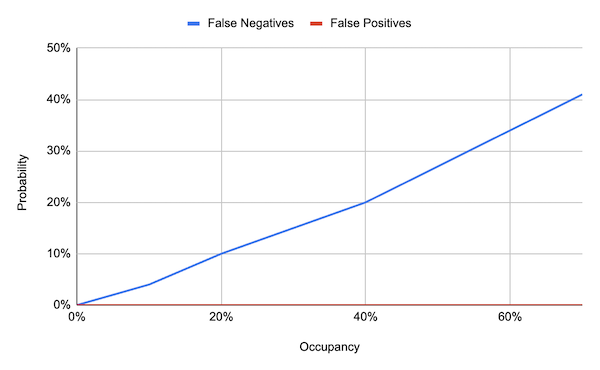

For l = 16, b = 128, N = 1,000,000 and M = 100,000, we obtain the following result:

The linear growth with occupancy (a loose proxy for the number of inserted $n$), matches the estimate of $n/2^{l}$ from Proposition 1.

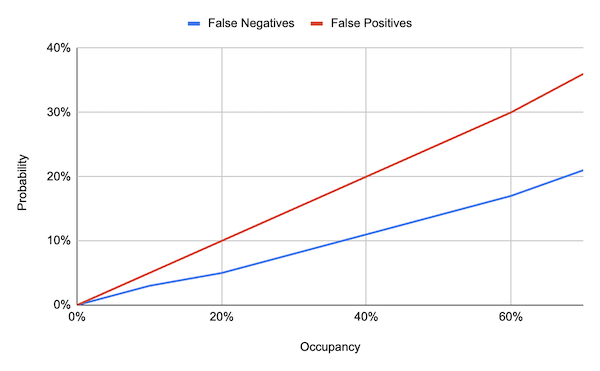

We can try to have some false positives by having b be very small, for example, just one bit. For l = 16, b = 1, N = 1,000,000 and M = 100,000, we obtain the following result:

This result suggests that the probability of false positives is not $1/2^{p + b}$, because for this case we’d have a probability of $1/2^{17}$, whereas for higher occupancy we observed $36\%$ of false positives. This is however consistent with $1/2^b = 50\%$ from Proposition 2.

The full implementation and experimentation code is available on Github.

Conclusion

The main takeway from the investigation is that negative Bloom filters don’t exist. In the process I did learn about an implementation of a LRU cache that is about 128 bigger than a Bloom filter but in practice it has the guarantees we needed for our problem.

In the end for our application the keys are 64-bit ids, so storing 128-bit for them wasn’t worth it and using a off-the-shelf LRU cache turned out to be simpler.

This cache solution also has builtin TTL support, which is very important for our use negative cache use case and is notably complicated to do with a Bloom filter. However the approximate set discussed above handles this nicely by replacing keys on collision.