kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Protein Design

Protein Design

30 Sep 2019

We previously learned about the problem of predicting the folding of a protein, that is, given a chain of amino acids, find its final 3D structure. This time we’re interested in the reverse problem, that is, given a 3D structure, find some chain of amino-acid that would lead to that structure once fully folded. This problem is called Protein Design.

In this post we’ll focus on mathematical models for this problem, studying its computational complexity and discuss possible solutions.

Mathematical Modeling

The 3D structure of a protein can be divided into two parts: the backbone and the side chains. In the model proposed by Piece and Winfree [3], we assume the backbone is rigid and that we’ll try to find the amino-acids for the side chains such that it minimizes some energy function.

This means we’re not really trying to predict the whole chain of amino acids, but a subset of those amino that will end up on the side chains.

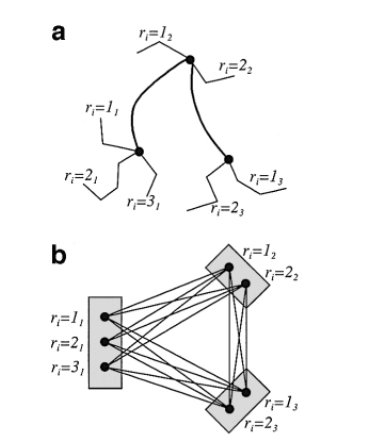

The amino acids on the side-chain can have a specific orientation [2, 3], known as rotamer, which in turn can be represented by a single value, its dihedral angle. We can define some arbitrary order for these amino acids and label them with an index, which we call position.

At each position there are multiple rotamers possible and we need to select them to minimize the overall energy function. More formally, for each position i, let \(R_i\) be the set of rotamers available and \(r_i \in R_i\) the chosen rotamer.

The model assumes the cost function of the structure is pairwise decomposable, meaning that we can account for the interaction of each pair independently when calculating the total energy:

Where \(E(r_i, r_j)\) is the energy cost of the interaction between positions i and j, assuming rotamers \(r_i\) and \(r_j\) respectivelly. The definition of E can be based on molecular dynamics such as AMBER.

In [3], the authors call this optimization problem PRODES (PROtein DESign).

PRODES is NP-Hard

Pierce and Winfree [3] prove that PRODES is NP-Hard. We’ll provide an informal idea of the proof here.

First we need to prove that the decision version of PRODES is NP-Hard. The decision version of PRODES is, given a value K, determine whether there is a set of rotamers such that the energy cost is less or equal K. We’ll call it PRODESd. We can then prove that PRODESd is NP-complete by showing that it belongs to the NP complexity class and by reducing, in polynomial time, some known NP-complete problem to it.

We claim that this problem is in NP because given an instance for the problem we can verify in polynomial time whether it is a solution (i.e. returns true), since we just need to evaluate the cost function and verify whether it’s less than K.

We can reduce the 3-SAT problem, known to be NP-complete, to PRODESd. The idea is that we can map every instance of the 3-SAT to an instance of PRODESd and show that the result is “true” for that instance of 3-SAT if and only if the result is “true” for the mapped instance of PRODESd.

Let’s start by formalizing PRODESd as a graph problem, with an example shown in the picture below:

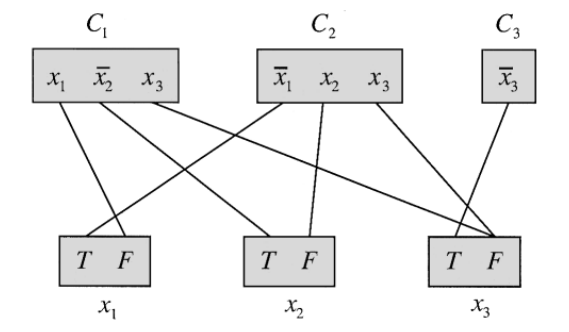

Now, given a 3-SAT instance, we create a vertex set for each clause \(C_i\) (containing a vertex for each literal), and a vertex set for each variable \(x_i\) (containing vertices T and F). For each literal \(x_i\) we add an edge of weight 1 to the vertex F of the set corresponding to variable \(x_i\). Conversely, for each negated literal, \(\bar x_i\), we add an edge of weight 1 to the vertex T. All other edges have weight 0.

For example, the instance \((x_1 + \bar x_2 + x_3) \cdot ( \bar x_1 + x_2 + x_3) \cdot (\bar x_3)\) yields the following graph where only edges of non-zero weight are shown:

We claim that this 3-SAT instance is satisfiable if and only if the PRODESd is true for K=0. The idea is the following: for each vertex set corresponding to a variable we pick either T or F, which corresponds to assigning true or false to the variable. For each vertex set corresponding to a clause we pick a literal that will evaluate to true (and hence make the clause true). It’s possible to show that if 3-SAT is satisfiable, there’s a solution for PRODESd that avoids any edge with non-zero weight.

Integer Linear Programming

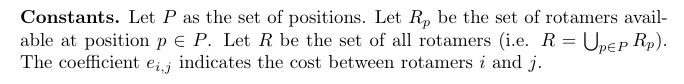

Now that we know that PRODES is unlikely to have an efficient algorithm to solve it, we can attempt to obtain exact solutions using integer linear programming model. Let’s start with some definitions:

We can define our variables as:

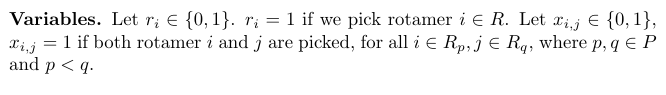

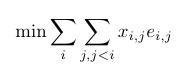

The object function of our model becomes:

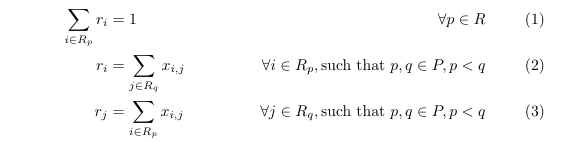

Finally, the constraints are:

Equation (1) says we should pick exactly one rotamer for each position. Constraints (2) and (3) enforce that \(x_{i, j} = 1\) if and only if \(r_i = r_j = 1\).

Note: the LaTeX used to generate the images above are available here.

Conclusion

The study of protein prediction led me to protein design, which is a much simpler problem, even though from the computational complexity perspective it’s still an intractable problem.

The model we studied is very simple and makes a lot of assumptions, but it’s interesting as a theoretical computer science problem. Still I’m not sure how useful it is in practice.