kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Protein Folding Prediction

Protein Folding Prediction

06 Sep 2019

In this post we’ll study an important problem in bioinformatics, which consists in predicting protein folding using computational methods.

We’ll cover basic concepts like proteins, protein folding, why it is important and then discuss a few methods used to predict them.

Amino Acids and Proteins

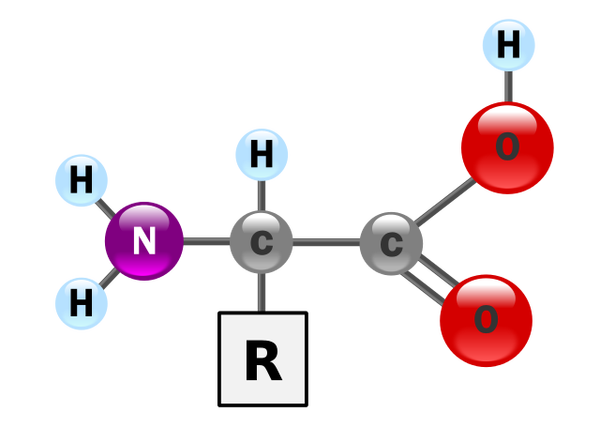

Amino acids are any molecules containing an Amino (-NH2) + Carboxyl (COOH) + and a side chain (denoted as R), which is the part that varies between different amino acids [1].

Etymology. A molecule containing a carboxyl (COOH) is known as carboxylid acid, so together with the Amino part, they give name to amino acids [2].

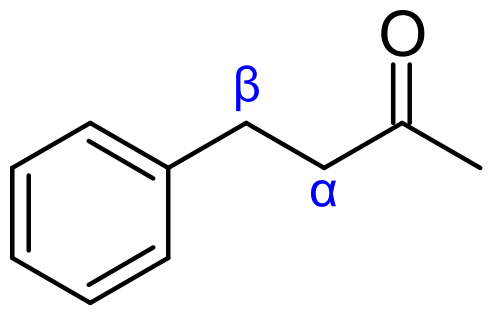

An amino acid where R attaches to the first carbon (see Figure 1) is known as α-amino acids (read as alpha amino acids).

There are 500 different amino acids known, but only 22 of them are known to be present in proteins and all of them are α-amino acids. Since we’re talking about proteins, we’ll implicitly assume amino acids are the alpha amino ones. See Figure 2.

Amino acids can be chained, forming structures known as pepitides, which in turn can be chained forming structures like polipeptides. Some polipeptides are called proteins, usually when they’re large and have some specific function, but the distinction is not precise.

Etymology.Peptide comes from the Greek to digest. According to [3], scientists Starling and Bayliss discovered a substance called secretin, which is produced in the stomach and signals the pancreas to secrete pancreatic juice, important in the digestion process. Secretin was the first known peptide and inspired its name.

Protein Folding

To be functional, a protein needs to fold into a 3-D structure. The sequence of amino acids in that protein is believed [6] to be all that is needed to determine the final shape of a protein and its function. This final shape is also known as native fold.

There are 4 levels of folding, conveniently named primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary.

- Primary structure is the non-folded form, the “linearized” chain of amino acids.

- Secondary structure is formed when parts of the chain bond together via hydrogen bonds, and can be categorized into alpha-helix and beta-strands.

- Tertiary structure is when the alpha-helix and beta-sheet fold onto globular structures.

- Quaternary structure is when 2 or more peptide chains that have already been folded combine with each other.

Prediction

The prediction of protein folds usually involves determining the tertiary (most common form) structure from its primary form. We’ve seen before in DNA Sequencing that reading amino acid sequences is easier when its denatured into a linear chain. On the other hand, analyzing the intricate folded forms can be very hard [7], even with techniques such as X-ray crystalography.

Why is this useful?

If the protein structure is known, we can infer its function on the basis of structural similarity with other proteins we know more about. One can also predict which molecules or drugs can efficiently bind and how they will bind to protein [7].

From Wikipedia’s Nutritious Rice for the World [8], protein prediction can also help understand the function of genes:

… prediction tools will determine the function of each protein and the role of the gene that encodes it.

Computational Methods

In this section we’ll focus on the computation methods used to aid the prediction of protein folds. There are 2 main types, template based and de novo.

Template based methods rely on proteins with known folds which can be used as template for determining the fold of a target protein with unknown fold. This only works well if the target protein is similar enough to the “template” one, or has some shared ancestry with it, in which case they are said to be homologous.

De novo methods do not rely on existing protein for templates. It uses known physico-chemical properties to determine the native structure of a protein. We can model the folding as an optimization problem where the cost function is some measure of structure stability (e.g. energy level) and steps are taken to minimize such function given the physico-chemical constraints. Molecules that have the same bonds but different structures are known as conformations, which form the search space of our optimization problem.

Let’s now cover some implementations of de novo methods.

Rosetta

One implementation of de novo method is the Rosetta method [9]. It starts off with the primary form of the protein. For each segment of length 9 it finds a set of known “folds” for that segment. A fold in this case is represented by torsion angles on the peptide bonds. The search consists in randomly choosing one of the segments and applying the torsion of its corresponding known folds to the current solution and repeat.

Note that while this method does not rely on protein templates, it still assumes an existing database of folds for amino acid fragments. However, by working with smaller chains, the chances of finding a matching template are much higher.

AlphaFold

One major problem with de novo methods is that they’re computationally expensive, since it has to analyze many solutions to optimize them, which is a similar problem chess engines have to.

Google’s DeepMind has made the news with breakthrough performance with its Go engine, AlphaGo. They used a similar approach to create a solver for protein folding prediction, AlphaFold. This approach placed first in a competition called CASP.

CASP is a competition held annually to measure the progress of predictors. The idea is to ask competitors to predict the shape of a protein whose native fold is known but not public.

Crowdsourcing

Another approach to the computational costs involved in the prediction is to distribute the work across several machines. One such example is Folding@home, which relies on volunteers lending their idle CPU time to perform chunks of work in a distributed fashion which is then sent back to the server.

An alternative to offering idle CPU power from volunteers’ machines is to lend CPU power from their own brains. Humans are good at solving puzzles and softwares like Foldit rely on this premise to find suitable folds. According to Wikipedia:

A 2010 paper in the science journal Nature credited Foldit’s 57,000 players with providing useful results that matched or outperformed algorithmically computed solutions

Conclusion

Here are some questions that I had before writing this post:

- What is protein folding? Why predicting it important?

- What are some of the existing computational methods to help solving this problem?

Questions that are still unanswered are details on the algorithms like the Rosetta method. I also learned about Protein Design in the process, which I’m looking into studying next. The approach used by DeepMind seem very interesting, but as of this writing, they haven’t published a paper with more details.

As a final observation, while researching for this post, I ran into this Stack Exchange discussion, in which one of the comments summarizes my impressions:

This field is pretty obscure and difficult to get around in. There aren’t any easy introductions that I know of. I found that the information available is often vague and sparse. I’d love to find a good textbook reference to learn more details. One possible explanation is that this field is relatively new, and there’s a lot of proprietary information due to this being a lucrative field.

References

- [1] Wikipedia - Amino acid

- [2] Wikipedia - Carboxylic acid

- [3] The Research History of Peptide

- [4] Wikipedia - Homology modeling

- [5] Wikipedia - Threading (protein sequence)

- [6] Wikipedia - De novo protein structure prediction

- [7] Quora: Why is protein structure prediction important?

- [8] Wikipedia - Nutritious Rice for the World

- [9] The Rosetta method for Protein Structure Prediction

- [10] AlphaFold: Using AI for scientific discovery