kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Content Delivery Network

Content Delivery Network

21 Jul 2019

In this post we’ll explore the basics of a Content Delivery Network (CDN) [1].

Outline

Here are the topics we’ll explore in this post.

- Introduction

- Advantages

- Definitions

- Caching

- Routing

Introduction

Content Delivery Networks, in a simplistic definition, is like the cache of the internet. It serves static content to end users. This cache is a bunch of machines that are located closer to the users than data centers.

Differently from data centers that can operate in a relatively independent manner, the location of CDNs are subject to the infrastructure of internet providers, which means a lot more resource/space sharing between companies is necessary and there are more regulations.

Companies often use use CDNs via third-party companies like Akamai and Cloudflare, or, as it happens with large internet companies like Google, go with their own solution.

Let’s see next reasons why a company would spend money in CDN services or infrastructure.

Advantages

CDNs are closer to the user. Due to smaller scale and partnerships with internet providers, CDN machines are often physically located closer to the user than a data center can be.

Why does this matter? Data has to traverse the distance between the provider and the requester. Being closer to the user means lower latency. It also less hops to go through, meaning less required bandwidth [2].

Redundancy and scalability. Adding more places where data live increases redundancy and scalability. Requests will not go all to a few places (data centers) but will hit first the more numerous and distributed CDNs.

Due to shared infrastructure, CDN companies can shield small companies from DDoS attacks by distributing traffic among its own servers, absorbing the requests from the attack.

Improve performance of TLS/SSL connections. For websites that use secure HTTP connections, it’s necessary to perform 2 round-trips, one to establish the HTTP connection, another to validate the TLS certificate. Since CDNs must connect to the data center to retrieve the static content, it can leverage that to keep the HTTP connection alive, so that subsequent connections from client to data centers can skip the initial round trip [3].

Before we go into more details on how CDNs work, let’s review some terminology and concepts.

Definitions and Terminology

Network edge. is the part of network before a request traverses before reaching the data center. Think of the data center as a polygonal area and the edge being the perimeter/boundary.

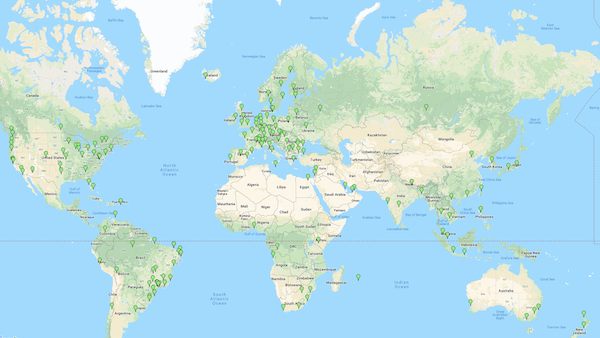

Internet exchange points (IXP). It’s a physical location containing network switches where (Internet Service Provider) ISPs connect with CDNs. The term seems to be used interchangeably with PoP (Point of Presence). According to this forum, the latter seems an outdated terminology [4]. The map below shows the location of IXP in the world:

Border Gateway Protocol (BGP). The BGP is used for routing traffic between different ISPs. To connect a source IP with its destination, the connection might need rely on a networks from different a different provider than the original one.

CDN peering. CDN companies rely on each other to provide full world coverage. The cost of having a single company cover the entire world is prohibitive. Analogous to connections traversing networks from multiple ISPs.

Origin server. To disambiguate between the CDN servers and the servers where the original data is being served from, we qualify the latter as origin server.

Modes of communication. There are four main modes [5]:

- Broadcast - one node sends a message to all nodes in the network

- Multicast - one node sends a message to a subset of the nodes in the network (defined via subscription)

- Unicast - one node sends a message to a specific node

- Anycast - one node sends a message to another node, but there’s flexibility to which node it will send it to. ISP Tiers. Internet providers can be categorized into 3 tiers based on their network. According to Wikipedia [6] there’s no authoritative source defining to which tier networks belong, but the tiers have the following definition:

- Tier 1: can exchange traffic with other Tier 1 networks without paying for it.

- Tier 2: can exchange some traffic for free, but pays for at least some portion of it.

- Tier 3: pays for all its traffic. Most of ISPs are Tier 2 [7].

Caching

One of the primary purposes of a CDN is caching static content for websites [8]. The CDN machines act as a look through cache, that is, the CDN serves the data if cached, or makes a request to the origin server behind the scenes, caches it and then returns it, making the actual data fetching transparent to the user. We can see that the CDN acts as a proxy server, or an intermediary which the client can talk to instead of the origin server.

Let’s consider the details of the case in which the data is not found in the cache. The CDN will issue an HTTP request to the origin server. In the response the origin server can indicate on their HTTP header whether the file is cacheable with the following property:

Cache-Control: public

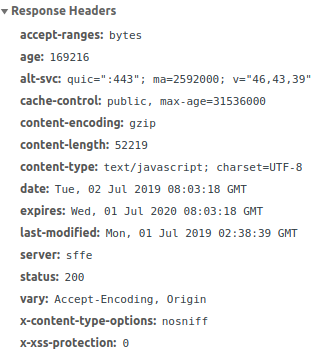

For example, if we visit https://www.google.com/, we can inspect the network tab and look at the HTTP response header of a random JavaScript file:

we can see the line cache-control: public. In fact, if we look at the origin of this file, we see it’s coming from the domain www.gstatic.com which is Google’s own CDN.

www.gstatic.com/og/_/js/k=og.og2.en_US.mOcfcqNpMkc.O/rt=j/m=drt,def/exm=in,fot/d=1/ed=1/rs=AA2YrTtfvY3V9vNuxwOxTw6H0xc0DK_I7ACaching and Privacy

One of the important aspect of caching is to make sure privacy is honored. Consider the case of a private photo that is cached by a CDN. We need to make sure that it’s highly unlikely that someone without access will be able to see it.

Since CDNs store the static content but not the logic that performs access control, how can we make it privacy-safe? One option is to generate an image path that is very hard to reverse-engineer.

For example, the origin server could hash the image content using a cryptographic hash function and use that as the URL. Then, the corresponding entry in the CDN will have that name.

In theory if someone has access to the URL they can see my private photo but for this to happen I’d need to share the image URL, which is not much different from downloading the photo and sending to them. In practice there’s an additional risk if one uses a public computer and happen to navigate to the raw image URL. The URL will be in the browser history even if the user logs out. For reasons like these, it’s best to use incognito mode in these cases.

To make it extra safe the server could generate a new hash every so often so that even if someone got handle of an URL, it will soon be rendered invalid, minimizing unintended leaks. This is similar to the concept of some strategies for 2-fac authentication we discussed previously where a code is generated that makes the system vulnerable very temporarily.

Routing

Because CDNs is in between client and origin server, and due to its positioning, both physical and strategical, they can provide routing as well. According to this article from Imperva [9], this can mean improved performance by use of better infrastructure:

Much focus is given to CDN caching and FEO features, but it’s direct tier 1 network access that often provides the largest performance gains. It can revolutionize your website page load speeds and response times, especially if you’re catering to a global audience. CDNs are often comprised of multiple distributed data centers, which they can leverage to distribute load and, as mentioned previously, protect against DDoS. In this context, we covered Consistent Hashing as a way to distribute load among multiple hosts which are constantly coming in and out of the availability pool.

CDNs can also rely on advanced routing techniques such as Anycast [10] that performs routing at the Network Layer, to avoid bottlenecks and single point of failures of a given hardware.

Conclusion

I wanted to understand CDNs better than being “the cache of the internet”. Some key concepts were new to me, including some aspects of the routing and the ISPs tiers.

While writing this post, I realized I know very little of the practical aspects of the internet: How it is structured, its major players, etc. I’ll keep studying these topics further.

References

- [1] Cloudflare - What is a CDN?

- [2] Cloudflare - CDN Performance

- [3] Cloudflare - CDN SSL/TLS | CDN Security

- [4] Cloudflare - What is an Internet Exchange Point

- [5] Cloudflare - What is Anycast?

- [6] Wikipedia - Tier 1 network

- [7] Wikipedia - Tier 2 network

- [8] Imperva - CDN Caching

- [9] Imperva - Route Optimization

- [10] Cloudflare - Load Balancing without Load Balancers