kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Cell biology and Programming

Cell biology and Programming

30 Apr 2018

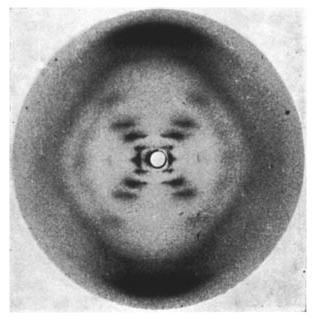

Rosalind Franklin was an English chemist and X-ray crystallographer. She is best known for her work on the X-ray diffraction images of DNA, particularly Photo 51 (Figure 1), while at King’s College, London, which led to the discovery of the DNA structure by Watson and Crick.

James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. According to Wikipedia [1], Watson suggested that Franklin would have ideally been awarded a Nobel Prize in Chemistry four years after Franklin passed away due to ovary cancer.

In this post we’ll study some basic concepts of cell biology, mostly around the DNA. We’ll start by introducing the structure of the DNA and then two of its main functions: replication and synthesis of protein. Since this is a programming blog, we’ll provide analogies (some forceful) to computer systems to help us relate to prior knowledge.

The end goal of this post to provide a good basis for later learning bio-informatics algorithms.

Genome

Genome is the set of information necessary for creating an organism. In a computer programming analogy we can think of the genome as the entire source code of an application.

Chromosome

Let’s recall that cells can be classified into two categories, eukaryotic (from the Greek, good + nucleus) and prokaryotic (before + nucleus). As the name suggests, eukaryotic cells have a well define nucleus surrounded by a membrane.

In eukaryotic cells the genome is divided across multiple chromosomes which are basically compacted DNA. They need to be compacted to fit within the nucleus. According to Science Focus [3], if stretched, the DNA chain would be 2 meters long.

Humans cells usually have 23 pairs of chromosomes, 22 of which are called autosomes and they are numbered based on size (autosome 1 is the largest). The remaining is a sex chromosome and can be of type either X or Y.

Men and women share the same types of autosomes, but females have two copies of chromosome X, and men one chromosome X and one Y.

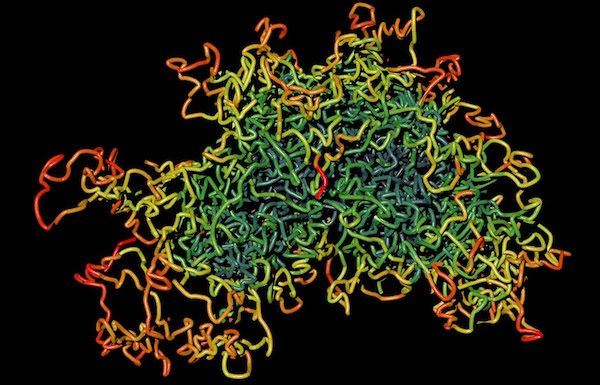

Chromosomes are usually depicted as X-like structures and neatly arranged [4], but recent research was able to visualize the actual structure and it looks more like Figure 2.

Prokaryotes (e.g. bacteria) on the other hand typically store their entire genome within a single circular DNA chain.

In our computer programming analogy, the chromosome serve as units of organization of the source code, for example the files containing the code. If your application is simple, like a bacteria, the entire source code could be stored in a single file!

We can push the analogy even further and think of the tangled DNA within the chromosome as the “minification” step that JavaScript applications apply to the original source code to reduce network payload.

DNA

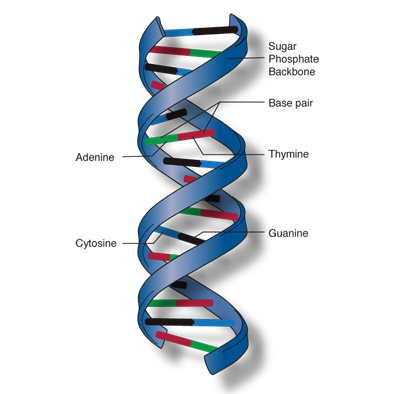

The deoxyribonucleic acid, more commonly known as DNA is a structure usually composed of two strands (chains) connected through “steps” to form a double helix, like in Figure 3.

In our analogy the DNA could represent the text of the source code.

Nucleotide

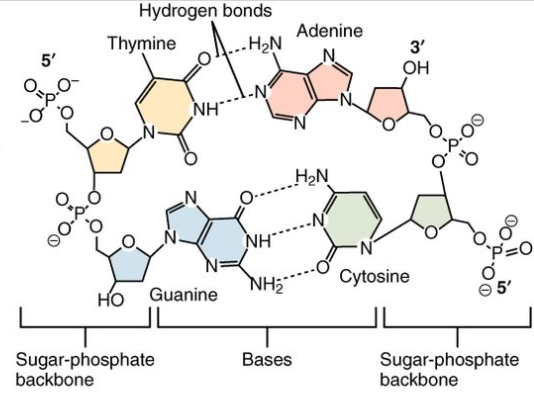

Nucleotides are the discrete units that form the base of the DNA. In the DNA it can be one of: Adenine, Cytosine, Guanine and Thymine.

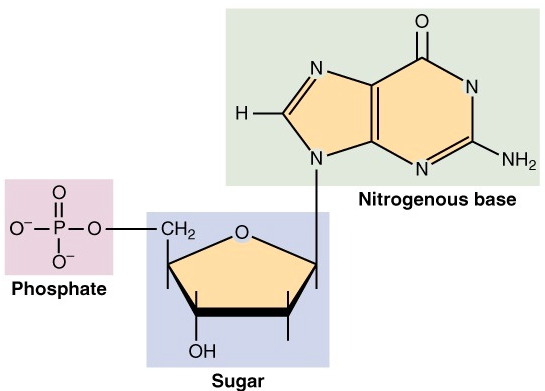

Chemically speaking, we can divide the nucleotide in 3 parts: a sugar group, a phosphate group and a nitrogen base (see Figure 4). The first two are common among the nucleotides, while the base differentiates them.

Any two nucleotides can be connected through their sugar and phosphate groups (the sugar group of one nucleotide links to the phosphate group of the next). Nucleotides linked this way form the backbone of a single strand of the DNA.

In addition, two nucleotides can be linked together via their nitrogen base (via a hydrogen bond), but in this case, there’s a restriction on which two bases can be linked together. Adenine can only be paired with Thymine, and Cytosine can only be paired with Guanine. These pairings form the “steps” in between two DNA strands. Figure 5 depicts these bonds.

Because the phosphate group of a nucleotide is linked to the sugar group of the next, we can define a direction for a chain of nucleotides. The endpoint that ends with the phosphate group has 5 carbon molecules and is called 5’ (read as five prime), while the sugar group has 3 and is called 3’ (three prime). The two strands in a DNA molecule are oriented in opposite directions, as depicted in the figure above.

We can now complete the analogy of computer programming by stating that nucleotides are the characters that compose the text of the source code (DNA). In our case, the alphabet contains 4 letters: A (Adenine), C (Cytosine), G (Guanine), T (Thymine).

The replication

The DNA is capable of replicating itself so that it can be passed down to new formed cells.

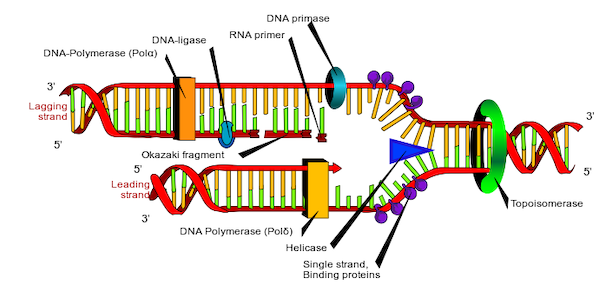

In high-level, the double strands of the DNA start separating and other structures start binding new nucleotides to each strand (templates) until both the strands are completely duplicated (and form a double strand again).

The separation of the strands is triggered by the protein helicase, and can happen at any point of the DNA and it might happen in many places at the same time. One way to visualize this is opening a zipper jacket from the middle and keep pushing it open in one direction.

While the strands are being separated, proteins called DNA polymerase starts scanning each strand and making a copy strand by adding nucleotides to it.

The DNA polymerase can only extend an existing chain of nucleotide, so it requires an initial fragment to start with. For that reason, in the beginning of the duplication process, a small fragment of DNA or RNA, called primer, needs to be connected to the strand.

One important limitation the polymerase has is that it can only process a strand in one specific direction: from 3’ to 5’. But since we saw that strands are oriented in opposite direction of each other, it means that the replication process doesn’t happen symmetrically on both strands.

For the strand oriented 3’ to 5’ the replication is smooth, generating a continuous strand. For the reverse strand though, it will be done in pieces, because the polymerase is adding nucleotides in the opposite side of where the opening is happening. These pieces are known as Okazaki fragments and later joined together by another protein called ligase.

We can see these two cases taking place in Figure 6:

One interesting fact about this process is that errors do happen and there are error corrections in place to minimize them. The result of the replication is also not 100% accurate, especially at the endpoints of the strands, where each new replica formed has its endpoints shorter than the original template. To compensate for this, the DNA has repeated redundant segments of nucleotides at the endpoints, know as telomeres, but eventually this extra segments get wore off to a point they cannot be used for replication. The shortening of telomeres is associated with aging.

In our analogy to computer programming, we could imagine the replication being the distribution of copies of the source code to other people. This analogy is weak, though. If we want to be precise, we’d need to come up with a program that is capable of printing its own source as output. This was named Quine by Douglas Hofstadter in Gödel, Escher, Bach [6] and it’s an example of a self-replicating automata, also studied by the famous computer scientist John von Neumann.

Protein Production

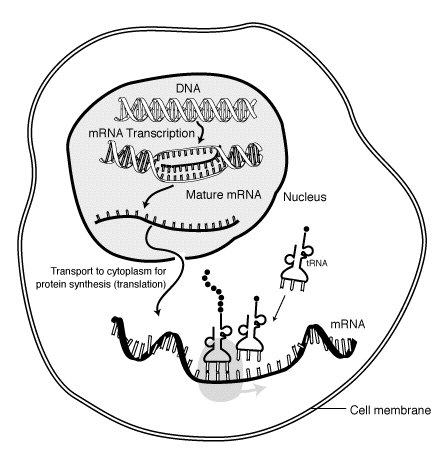

A second function of the DNA is the production of proteins. The first step, called transcription, is very similar to replication: One of the strands serve as template, and a new strand with complementary base is generated. The difference is that instead of Thymine, the nucleotide Uracil is used. The resulting structure is called mRNA, short for messenger RNA.

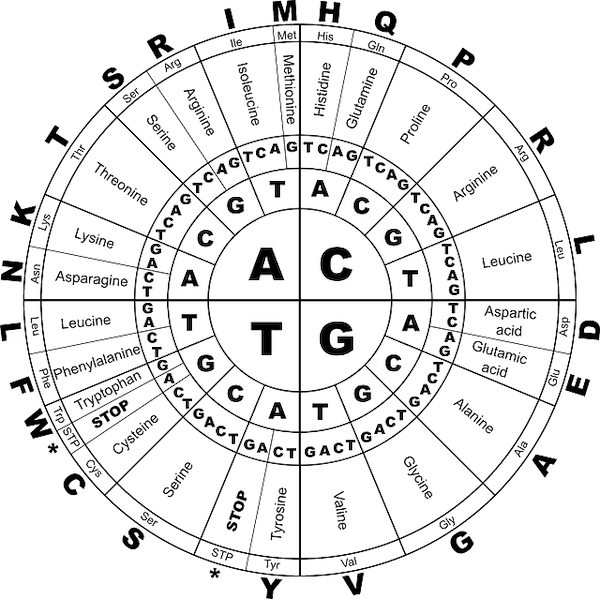

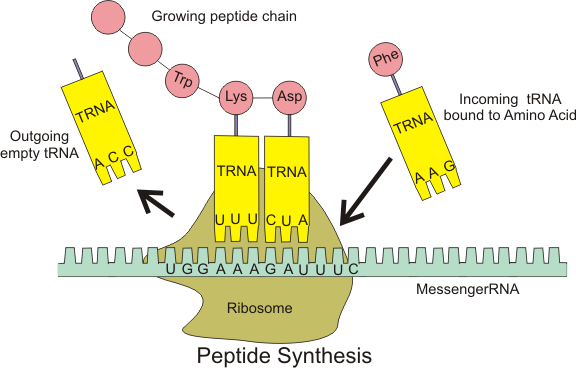

The mRNA detaches itself from the DNA strand and exits the nucleus to the cytoplasm where the second step, translation, begins. In there, it is “interpreted” by a structure called ribosome. Every 3 nucleotides, denominated codon, translates to an amino acid, which in turn form a protein. The mapping of every possible 64 combinations of codons are displayed in Figure 8.

The tRNA, short for transfer RNA, is a small chain of RNA that connects amino-acids to their corresponding codon in the mRNA. There are some special codons that indicate the end of the process. The output of this translation will be a peptide chain.

The production of protein is the actual functioning of the DNA. If we link to the computer programming model, we could think of the source code (DNA) being interpreted or compiled into an actual program that can be executed. It’s incredible how biological systems evolved to define an explicit code for the end of the translation, much like how a semi-color or new line often indicates the end of an expression.

Applications of Bio-informatics

How can computer science help with the study of biological systems? Computers are good at repetitive tasks and handling large amounts of data. Here are some applications according to Wikipedia [7].

- DNA sequencing - consists of determining the order of nucleotides in the DNA from raw data. Computers are useful here because the raw data often come as fragments that need to be merged.

- Protein structure prediction - given a sequence of nucleotides, determine the chain of amino-acids is well-understood, but predicting the structure of the final protein is an open problem.

- Reduce noise in massive datasets output by experiments.

Conclusion

From reading a lot of introductory material, I felt that there were a lot of imprecise or ambiguous descriptions. That seems to come from the sheer complexity of biological systems and most results coming from empirical evidence, which currently only provide an incomplete picture of the whole, but new information still comes at a very frequent pace, sometimes making existing models obsolete or incorrect.

I last studied Biology back in high school. I don’t intend to study it in depth, but just enough to understand how computer science can be used to solve particular problems.

The idea of modeling living organisms as organic computers is fascinating. As we discover more about the inner workings of cells, I hope we can come up with better models and be able to predict their outcome with greater accuracy.