kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > On Complex Systems

On Complex Systems

20 Dec 2025

Four years ago I decided to change teams within my company. In doing so, I went from doing frontend work on internal tools to doing backend work on a large distributed system. In this new team it was the first time I had to deal with a really complex system.

In this post I’d like to share my thoughts on this topic.

Code vs. System Complexity

When I compare the projects I worked on, I can say that both had large and complex codebases.

However, the frontend system I worked on was relatively simple: usually we only had to think at a single node-level (user’s computer or a stateless webserver) and a single-thread. Also, at least at my company, there’s a dedicated team to handle scaling, running the webservers, deploying the code, etc.

For the backend system I work on nowadays, I often need to be aware of the existence of other nodes and how work is distributed among them, noisy neighbors, whether the code is thread-safe, or whether the work is I/O or CPU bound. In C++ in particular, I have to be aware of accidental copies and object lifetimes. Operationally, we need to scale the system ourselves (both horizontally and vertically), setup CI/CD, manually inspect stuck processes that escaped automated remediation.

This makes becoming familiar with a component of the system a lot harder, and a lesson I had to learn on transitioning is that I can’t expect to know all parts of the system and have to rely a lot more on teammates for day-to-day work.

Reasoning about a Complex System

I think a good way to determine how complex a system is, is based on the difficulty to reason about it. For example, in the old project I worked on, if something is slow, you usually can add cache, reduce the amount of payload, do things asynchronously, optimize SQL queries and there’s a good chance it will work.

In complex systems even finding the source of slowness can be very challenging. Sometimes a performance issue is data induced. The easy and obvious case is when the input throughput increases, in which case we can root cause it quickly. Other times it’s a bug in the data producer that started sending empty keys that then gets hashed to the same consumer, causing hot key issues.

Red herrings are also a common issue. For example, if the system is using a lot of memory, performance can be degraded by multiple mechanisms. It could be page swapping, memory backpressure mechanism by the consumer reading data, local cache hit rate reduced due to less available memory, etc. This might manifest as low throughput, not in memory saturation metrics.

Even once we find the potential cause, when we try to speed things up it often doesn’t work as we expect or makes things worse. Some examples:

- After identifying a slow function via profiling, we increased the parallelism factor, but then the bottleneck switched to a dependency. The dependency couldn’t handle the increase traffic and started throttling or crashing, making throughput worse.

- After identifying a slow function via profiling, we increased the parallelism factor, which increased memory utilization which started causing OOMs.

- After noticing a job with multiple servers struggling, we try to scale it horizontally by adding more servers. It turned out only a few servers were lagging and was due to hot keys. Since our servers have key-affinity, scaling doesn’t help because the same hot keys are still going to the same few servers.

Another complication in improving performance is the vast amount of knobs that can be tuned. Due to organic growth knobs added overlap in how they work or are add odds with each other. For example, we can have a throttling mechanism that works either by having a threshold on data size or number of rows. Sometimes tweaking one has no effect because the existing setting for the other is the threshold being violated.

Automation

Automation in complex systems makes it even harder to reason about them. One example is the memory backpressure mechanism mentioned above, which was added to regulate memory usage automatically, but on the other hand makes it difficult to root cause performance.

Another example is an auto-scaling system, which is supposed to respond to increase in input traffic and scale up or out. The main metric it monitors is memory usage and throughput. If memory usage increases or throughput drops it automatically scales the system, either vertically (increasing memory limits) or horizontally, adding more nodes to it.

Once, we introduced a bug that caused a hot path to become slower so the throughput dropped across all our jobs. The auto-scaler tried to scaled all the jobs at the same time, which depleted the capacity from the fleet! Also, depending on how sensitive the auto-scaling is and throughput patterns, it can cause flapping (constantly scaling up and down).

These mechanisms that react automatically to change in the system remind me of Donella Meadows’ book Thinking in Systems. It becomes exceedingly complex when there are multiple such mechanisms acting independently of each other.

The Human Body

For of course the body is a machine. It is a vastly complex machine, many, many times more complicated than any machine ever made with hands;

Whenever I muse about the human body I think about complex systems. However hard to reason about, human-made complex systems have at least the benefit of being very observable. We can log all sorts of metrics and profile systems on demand, often with arbitrary levels of granularity.

The human body is a vastly more complex and the set of observations we can make is a lot more limited: blood tests, x-rays, stool tests, etc.

Our body is so difficult to understand that many Nobel prizes in physiology were awarded to people who figured out how some part of it works.

Complexity and Soft-Sciences

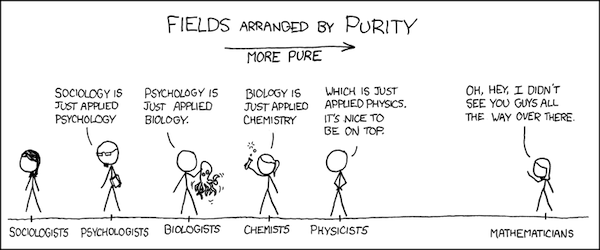

I’m of the opinion that the more you go to the right of the xkcd chart above, the deeper and more technical it becomes. It’s not because mathematicians are necessarily smarter than sociologists. It’s that the subject a sociologist studies is so complex that it’s impossible to be very deep or objectively precise about it.

I recently read i, robot by Isaac Asimov, which is a collection of short stories. One character that appears in most of the stories is Susan Calvin, which is a robo-psychologist, someone who can understand robots “minds”.

The idea is that AI gets so complex to understand that it becomes more like a soft-science. I share more on this topic in the section Robo-psychology of my review of the book.