kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > A Puzzling Calendar

A Puzzling Calendar

28 May 2022

I got a puzzle as gift recently called A-Puzzle-A-Day by Dragon Fjord Puzzles. It’s a wooden board with 43 cells, one for each month and 31 for days, plus 8 pieces of different shapes. The goal is to place the pieces covering all cells except those for the current month and day.

Here’s a possible solution for today:

More than solving puzzles I like writing puzzle solvers. In this post we’ll document the process for generating the image above.

Brute-force Solver

Estimating Cardinality

I was initially trying to estimate how many solutions a brute-force solver would need to try as a proxy of how long it would take to find a solution.

A back of envelope calculation is that we have 8 pieces, each of which can be rotated and flipped for a total of 8 configurations. Each configuration can be placed in one of the 41 cells (43 minus the 2 to remain), so the number of possible combinations is $(8 \cdot 41)^8$ or ~$10^{20}$. This is impractical but also this is a vast overestimation. Once pieces are placed, there a lot less positions the remaining places can be put in.

Another calculation is to consider a permutation of the pieces. For each permutation we try to place each piece in order greedly at the first available position. For each permutation we have to account for the 8 configurations of each piece, so the number of possible combinations is $8! \cdot 8^8$ or ~$10^{12}$, which is still too much.

Some pieces have symmetry that reduces the number of different configurations, like the rectangle which has only 2. I wrote a Python script to try refine the estimate but it got so involved that I figured I should just write the solver and see how long it runs for.

Algorithm

There were two approaches I considered:

1) Recursion on the pieces: try to place the i-th piece in each of the available spaces and then recurse over the remaining pieces.

2) Recursion on the positions: try to fill the i-th position with each remaining piece and then recurse over the available positions.

My hunch is that approach 1 would be less efficient. Suppose the first piece we place has the following configuration:

##....

.#....

##.....

.......

.......

.......

...Approach 1 would go maybe 5 levels further in the search before realizing this is infeasible while approach 2 would go maybe 2-3 levels before determining the second row first column cannot be covered and with a smaller branching factor. So I opted to go with approach 2.

Python Code

We introduce the classes Piece, Board and Solver. The solver is the most interesting part so let’s focus on it, in particular the backtrack() method. The idea is essentially approach 2 above. The full code is available on Github.

Variable self.coords contains a list of pairs of all available coordinates at the beginning of the backtrack. When we have traversed all coordinates we found a solution. Otherwise, if the current coordinate is occupied, there’s nothing to do, so we keep going.

Finally, we try each piece in turn, in all its forms, and then recurse. If we ever get a true response, we know a solution was found and can stop the search.

class Solver:

...

def backtrack(self, idx = 0):

if idx == len(self.coords):

self.sol = self.b.pieces_map.copy()

return True

coord = self.coords[idx]

b = self.b

if b.is_set(coord):

return self.backtrack(idx + 1)

for piece_id, forms in self.pieces_forms.items():

if b.has_piece(piece_id):

continue

for form in forms:

if not b.fits_at(form, coord):

continue

b.place_piece(form, coord)

r = self.backtrack(idx + 1)

b.remove_piece(form, coord)

if r:

return True

return FalseThe other interesting method is Board.place_piece(). We define the primary coordinate as the one with the lowest i-index (vertical), breaking ties with the lowest j-index (horizontal). For example, in the L shape below, the primary coordinate is (0, 2):

..#

..#

###The relative coordinates are shifted so that the primary coordinate is (0, 0), so for the example above the original coordinates are: (0, 2), (1, 2), (2, 0), (2, 1), (2, 2) but the relative ones are (0, 0), (1, 0), (2, -2), (2, -1), (2, 0).

We then attempt to place the piece such that its primary coordinate lies at the at position. Note that in backtrack() we call Board.fits_at() beforehand to make sure it’s possible to place the piece:

class Board:

...

def fits_at(self, piece, at):

coords = piece.relative_coords

return all(self.is_valid(coord + at) for coord in coords)

def place_pice(self, piece, at):

coords = piece.relative_coords

for coord in coords:

self.set_at(coord + at, piece.id)

self.pieces_map[piece.id] = [piece, at]Once we find a solution we record the position of each piece and its orientation. We can then run the backtrack for each month and day.

Pre-compute?

I was initially undecided on whether to pre-compute all the solutions upfront or solve it on-the-fly. Solving for a given day in Python takes ~2s. I don’t know how much better or worse running in JavaScript would be but not wanting to re-implement the solver and the possibility of burning browser CPU unnecessarily, I decided to pre-compute.

The solver generates $31*12 = 372$ entries each of each contains information about the $8$ pieces: position of the primary coordinate, number of rotations and whether it’s reflected, amounting to $48k$ bytes.

Display

For displaying the board we use SVG + React. Like in Python, the configuration of each piece is provided as a string map and read into a 0-1 matrix which we can rotate and reflect as needed. The most interesting part was generating the SVG polygon from such a matrix.

Polygon from Matrix

I struggled a bit to find an algorithm to do this and even looked up the Marching Squares, but then realized for this problem the matrix is simpler: the cells within a piece are connected by their sides. This means we don’t have cells connected by their vertices like this:

#.

.#First we build a directed graph. For each cell in position (i, j) we build four directed edges: (i, j) -> (i, j + 1), (i, j + 1) -> (i + 1, j + 1), (i + 1, j + 1) -> (i + 1, j) and (i + 1, j) -> (i, j).

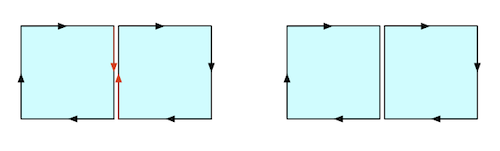

The key idea is that for adjacent cells, we’ll end up with “conflicting” edges a -> b and b -> a on their touching side. These are inner edges that do not show up in the polygon boundary. Once we remove these edges, we should be left with a circuit corresponding to the vertices of the polygon. See Figure 1 for an example.

There are many other ways to find the vertices of the polygon but I found this to have relatively few corner cases.

JavaScript Code

The JavaScript code (without some safety checks, for brevity) for computing the polygon coordinates follows. First we build the adjacency matrix. Piece.get_coords() is a list of [i, j] for the cells in the matrix equal to 1 and Pair is a utils to simplify 2-array arithmetic.

class Piece {

...

build_edge_map() {

const edges_map = {};

// vertices of square clock-wise

const deltas = [ [0, 0], [0, 1], [1, 1], [1, 0] ];

const coords = this.get_coords();

coords.forEach(coord => {

for (let k = 0; k < deltas.length; k++) {

const src = this.hash(Pair.add(coord, deltas[k]));

const next_delta = deltas[(k + 1) % deltas.length]

const dst = this.hash(Pair.add(coord, next_delta));

// rm duplicate edges

if (dst in edges_map && edges_map[dst].has(src)) {

edges_map[dst].delete(src);

} else {

if (!(src in edges_map)) {

edges_map[src] = new Set();

}

edges_map[src].add(dst);

}

}

});

return edges_map;

}

}Then we traverse the graph until we complete the circuit:

class Piece {

...

get_polygon_coords() {

// assumption: edges_map forms a circuit

const edges_map = this.build_edge_map();

const initial_coord = this.get_primary_coord();

let coord = initial_coord;

const pts = [initial_coord];

while (true) {

const adjs = Array.from(edges_map[this.hash(coord)]);

let next_coord = this.from_hash(adjs[0]);

if (Pair.eq(next_coord, initial_coord)) {

break;

}

coord = next_coord;

pts.push(coord);

}

// Normalize coordinates so primary coord is 0,0

return pts.map(pt => Pair.sub(pt, initial_coord));

}

}Generating the SVG polygon is now straightforward. We just need to translate and scale the coordinates so it is placed properly on the rest of the SVG board. sq_sz is the size of each cell in pixels and get_pos([i, j]) is the offset in pixels of the cell with indices [i, j].

const draw_polygon = (shape, [i, j], color) => {

const pts = shape.get_polygon_coords();

const pts_str = pts.map(pt => {

const pxl = get_pos([i, j]);

const [y, x] = Pair.add(Pair.mul(pt, sq_sz), pxl);

return `${x},${y}`;

}).join(" ");

return <polygon points={pts_str} fill={color} stroke="none" />;

}Stats

I modified the solver to count the number of solutions for each day and compute some statistics.

It took just under 1h to find 25,061 of them, with an average of 67.3 solutions per day! The day with the least solutions, October 6, has 7 and the day with the most solutions, January 25, has 216.

Conclusion

One thing I found surprising is how many solutions there are for any given day. I don’t have an intuition why this set of pieces yields so many valid arrangements.

I believe this is my first “live” post: the image of the puzzle changes every day.