kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > [Paper] FlumeJava

[Paper] FlumeJava

18 May 2022

In this post we’ll discuss the paper FlumeJava: Easy, Efficient, Data-Parallel Pipelines by Chambers et al [1]. In a nutshell, FlumeJava is a Java library to simplify the execution of multi-stage MapReduce jobs and was developed at Google.

Background

Before we start, let’s revisit MapReduce concept since it’s core to the premise of the FlumeJava library.

MapReduce

MapReduce is a distributed systems paradigm popularized by Google. It can be used to perform parallel computations by dividing the work across multiple machines.

A MapReduce job consists of 2 sets of machines: mappers and reducers. We provide a function to each of the mappers and another function to each of the reducers.

Each mapper receives a list of inputs and it applies the map function to each of them. Then, each result gets hashed to make up a key and depending on the key it goes to a reducer machine.

Each reducer receives the output from every single mapper that has the corresponding key. This distribution of the mappers’ outputs to the reducer’s input is called shuffling. The reducer applies the reduce function (often an aggregation) and writes the result to some persistent storage.

Suppose we want to count how many words start with each letter in a group a files, for example:

// a.txt

the early bird catches the worm

// b.txt

the squeaky wheel gets the greaseOne way to solve this using MapReduce is to provide a mapper function that returns the first letter of the word, for example:

def mapper(input: str) -> str:

return input[0]and then a reducer that counts how many entries with each letter exists

def reducer(key: str, values: List[str]) -> int:

return len(values)In our example, suppose we have 2 mappers and 2 reducers. File a.txt gets processed by the first reducer, and b.txt by the second. Let’s assume keys 'a'...'m' are processed by the first reducer and 'n'...'z' by the second.

The mappers will output:

// mapper 1's output

{t: 2, e: 1, b: 1, c: 1, w: 1}

// mapper 2's output

{t: 2, s: 1, w: 1, g: 2}The shuffling process will split the outputs into:

// mapper 1's split

{e: 1, b: 1, c: 1}, {t: 2, w: 1}

// mapper 2's split

{g: 2}, {t: 2, s: 1, w: 1}The reducers get and return:

// reducer 1:

{e: 1, b: 1, c: 1}, {g: 2} -> {e: 1, b: 1, c: 1, g: 2}

// reducer 2:

{t: 2, w: 1}, {t: 2, s: 1, w: 1} -> {t: 4, w: 2, s: 1}`The major value the MapReduce provides is to abstract the complexities of setting up and orchestrating a distributed system, including scaling and recovering from faults. In its most basic form, the user only needs to provide the mapper and reducer functions but it can get more complex.

Motivation

A single MapReducer provides a primitive that on its own can only be used to implement a limited set of computations. However, due to its simplicity it’s also highly modular and thus can be chained with other MapReducer jobs and form a direct acyclic graph (DAG).

This graph can become very complex and difficult to write and maintain. Moreover, it’s easy to construct inefficient graphs that perform redundant computations. The proposal from FlumeJava is an abstraction that makes expressing these graphs simpler and that performs optimizations behind the scenes.

I see an analogy here between MapReducer + FlumeJava and assembly + high-level languages. Assembly is harder to maintain while high-level languages provide better abstractions, and the compiler can optimize the code in a way that outperforms naive manual assembly optimizations.

API

Graph Building

The first part of interfacing with FlumeJava is to construct a graph by providing the functions to be computed and their dependencies.

Let’s consider a basic example. First we invoke a function readTextFileCollection() that reads strings from a file, stored in a distributed system (GFS). Note that this is not executing the actual reading, just building the graph. The P prefix stands for parallel.

PCollection<String> lines = readTextFileCollection(

"/gfs/data/shakes/hamlet.txt"

);For each line we read, we’ll split them into words by passing a corresponding lambda function to parallelDo(). The second argument to parallelDo() is collectionOf(strings()) which indicates the output type (PCollection<String>).

PCollection<String> words = lines.parallelDo(

new DoFn<String, String>() {

void process(String line, EmitFn<String> emitFn) {

for (String word : splitIntoWords(line)) {

emitFn.emit(word);

}

}

},

collectionOf(strings())

);We can then turn that list into a frequency map, to start each entry contains 1. Note that we use a list of pairs as opposed to a dictionary because it need to store duplicate keys.

PTable<String, Integer> wordsWithOnes = words.parallelDo(

new DoFn<String, Pair<String, Integer>>() {

void process(

String word,

EmitFn<Pair<String, Integer>> emitFn

) {

emitFn.emit(Pair.of(word, 1));

}

},

tableOf(strings(), ints())

);The variables words and wordsWithOnes should really computed in one pass though. This could be a good example of how a naive implementation ends up using two MapReduce jobs when one would suffice.

Finally we can group the pairs by key and then sum their values. The aggregation function SUM_INTS is part of the library but we could provide our own.

PTable<String, Collection<Integer>> groupedWordsWithOnes

= wordsWithOnes.groupByKey();

PTable<String, Integer> wordCounts =

groupedWordsWithOnes.combineValues(SUM_INTS);Note that combineValues() could replaced with parallelDo() but because the former assumes an aggregation, it can be optimized by also being executed by reducers as a pre-aggregation step (and reduce the amount of data on shuffling).

These basic primitives can be used to implement more complex operations common to SQL-engines like join() and top().

Execution

Then we call FlumeJava.run() which will optimize the graph, then create and run the MapReduce jobs. It’s then possible to consume the output as if the computation happened locally.

PObject<Collection<Pair<String, Integer>>> result =

wordCounts.asSequentialCollection();

FlumeJava.run();

for (Pair<String, Integer> count : result.getValue()) {

System.out.print(count.first + ": " + count.second);

}Optimization

Once the graph is built, there are a few performance optimizations that happen. The goal is to minimize the number of MapReduce jobs that get generated at the end.

ParallelDo Fusion

This consists in combining adjacent nodes corresponding to parallelDo() functions. This is a straightforward optimization. For example, if we have functions $f()$ followed by $g()$ we can combine them into a into a composition of them $(g \circ f)()$.

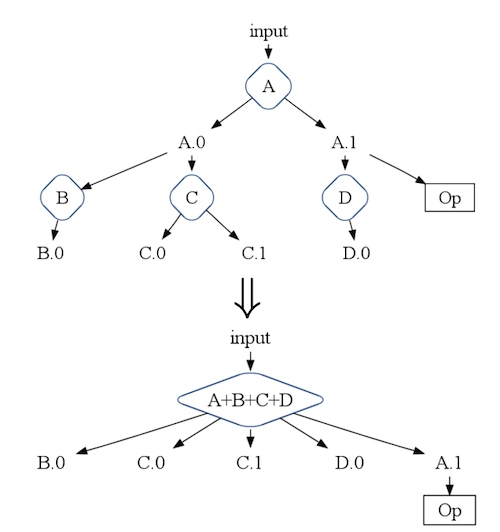

Since the reducer of the final MapReduce job allows multiple heterogenous output, we can also combine a parent and its children into one node, as in Figure 1.

Sink Flattening

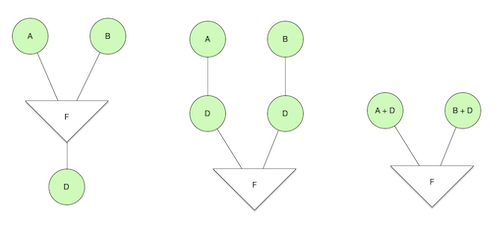

If two or more parallelDo()s, say A and B, follow a flatten operation and then fed into another parallelDo() D as in Figure 2, then we can duplicate D and “push it up” so it’s adjacent to A and B. This allows A + D and B + D to be fused, so we turned 3 functions into 2.

Grouping into MapReduce job units

The paper defines the MapShuffleCombineReduce (MSCR) abstraction, which is a 1:1 mapping with an actual MapReduce job. As the name suggests it encompasses a map, shuffle, combine and reduce sub-units.

Each groupBy() function will form its own MSCR and the combineValues() + parallelDo() nodes adjacent to it will be fused into its MSCR. Any remaining nodes after this process are parallelDo() ones, which go into trivial MSCRs with only a mapper.

Execution

For each MSCR the library will first determine whether to run the computation locally or to schedule a MapReduce job.

It stores the output of each MapReduce job in a temporary file (which I assume is in a distributed storage like GFS) but it deletes the file after the process is complete. These intermediate files can be also used as cache when the code is re-executed.

It also routes the stdout/stderr and exceptions of the user provided functions from the distributed machines back to the host machine.

Experiments

The authors compare FlumeJava with a naive MapReduce implementation, a hand-optimized MapReduce implementation and Sawzall, a DSL used for the same purposes as FlumeJava.

The experiments show that FlumeJava programs are smaller than their MapReduce counterparts but larger than Sawzall ones. It also shows that FlumeJava generates a number of MapReduce jobs comparable to hand-optimized MapReduce implementations and a fraction of those from naive MapReduce and Sawzall implementations.

FlumeJava vs. Lumberjack

The paper mentions a project called Lumberjack, a DSL that was also aimed at managing graphs of MapReduce jobs but was later scratched in favor of the Java-based FlumeJava. The motivations for this are:

- Cost in building and maintaining a DSL, not only the compiler/interpreter but the tooling around it.

- Low adoption due to having to learn a new language / syntax.

- Static generation of the graph which doesn’t allow dynamic use cases like re-running a graph until the results converges.

The interesting thing is that this paper was written in 2010, before Hive became popular. Hive is essentially a DSL that generates MapReduce jobs behind the scenes, but it uses SQL as its API.

It turns out that the API from FlumeJava can be naturally expressed in SQL and this is a familiar paradigm, especially for non-programmers. This explains the explosion in popularity of SQL=based distributed systems like Presto and Spark over the years.

Conclusion

To summarize, we learned that:

- FlumeJava is a Java library that abstracts the creation of a DAG of MapReduce jobs

- Users first define the graph via the FlumeJava API and then run it

- The library optimizes the graph to reduce the number of MapReduce jobs, including running things locally if possible

- The first attempt was a DSL (Lumberjack) but it had a lot of drawbacks

One thing the paper doesn’t seem to mention explicitly is how it handles fault-tolerance. I think it’s possible to completely defer it to the MapReduce framework which is fault-tolerant. If we assume each step of the execution is fault-tolerant I believe we can achieve fault-tolerance for the whole system though.

References

- [1] FlumeJava: Easy, Efficient Data-Parallel Pipelines - C. Chambers et al.