kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Linux Filesystems Overview

Linux Filesystems Overview

08 Feb 2021

In this post we’ll cover a diversity of topics concerning the Linux filesystem. We’ll start with a high-level overview a filesystem.

We then cover specific concepts such as types of filesystems, files, permissions. We continue by exploring some examples of commonly layout of the Linux directories hierachy.

This post expects some basic familiarity with Linux.

The Virtual Filesystem

The Virtual Filesystem, aka VFS, is a global class used by the kernel to represent a given filesystem.

The VFS Entities

There are 4 classes of objects the VFS keeps in memory.

Superblock. In-memory object with the metadata of a specific mounted filesystem.

Inode. In-memory object with the metadata for a specific file/directory (examples: permission, physical location - does not include filename or directory - see dentry)

Dentry. Short for directory entry. In-memory object that associates a file/directory with a path. According to [2]: dentry objects are constructed on the fly by th VFS.

File. Opened file associated with a process (more than one instance if multiple process are open)

All these objects provide an abstraction over specific implementations of the underlying filesystem (see Types of Filesystems) and are transparent to the kernel [2].

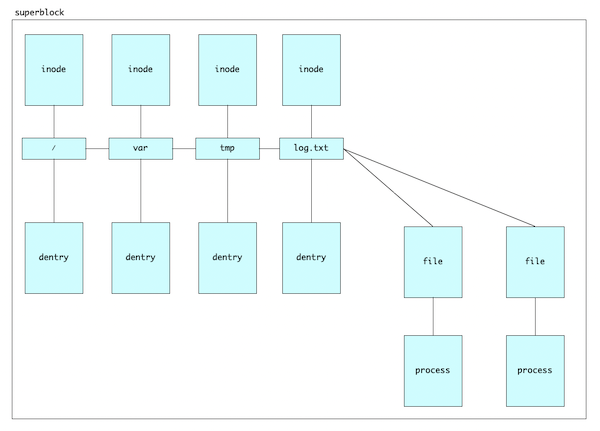

Example Diagram

Consider a file named log.txt located in /var/tmp/. The kernel will keep the following objects in memory:

Things to notice:

- Each “piece” of the path has a corresponding dentry object, including the root

/and the file itself. - The file object is not the source of truth for the file, but rather a connection (edge) between a process and the actual file.

- The inode has a 1:1 relationship with the file and has all the metadata about it.

Files

The anatomy of ls -l

We can get a lot of information from a file by typing (-l stands for “long”).

$ls -l

-rw-rw-r-- 1 kunigami kunigami 43315 Feb 6 09:48 tmp.txtThe first character on the first column (-) represents the file type which we’ll see in the File Types section.

The rest of the first column (rw-rw-r--) displays the permission information which we’ll see in the File Permissions section.

The next block has the number of files linked to that path. Note that is doesn’t include soft links. We’ll see hard and soft links within File Types > Links.

The third and fourth columns represent the user and group owners for that file. We’ll learn about groups in the section Groups.

The last columns (43315, Feb 6 09:48 and tmp.txt) represent the number of bytes in the file, the last modified date and its name.

Types of files

A lot of things are modelled as files in Linux, including directories and sockets. A common type of operation performed by the OS is transporting information from one place to another subject to some access control.

In Linux the concept of file abstracts such type of operations, so it can be seen as an interface which different components of the operating system can implement. Then many tools such as ls can operate over that abstraction.

As we saw above, we can inspect the type of a given file by reading the first character of ls -l:

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

- |

Regular file |

d |

Directory |

l |

Link |

c |

Character file |

s |

Socket |

p |

Named pipe |

b |

Block file |

We’ll now cover some of the types besides directories and regular files.

Link. represents a symlink or soft link file that is simply a pointer to another file. There are actually two types of file links:

- Soft link shares the same inode with the linked file.

- Hard link is a regular file with its own inode that points to the linked file.

Only the soft link is considered a special file. We can see this by running this code:

$touch file.txt

# soft link

$ln -s file.txt file_sl.txt

# hard link

$ln file.txt file_hl.txt

$ls -l

-rw-rw-r-- 2 kunigami kunigami 0 Feb 3 09:38 file_hl.txt

lrwxrwxrwx 1 kunigami kunigami 8 Feb 3 09:38 file_sl.txt -> file.txt

-rw-rw-r-- 2 kunigami kunigami 0 Feb 3 09:38 file.txtBlock and character files. These are hardware files and are used for reading/writing data. The major difference between block and character files as their names suggest is that the transferring of information is done block-by-block and character-by-character, respectively.

An example of a block file is the access to the hard disk and a character file the access to the keyboard. The /dev/ directory has a lot of these files:

$ls -l /dev/sda1

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 1 Dec 28 21:27 sda1$ls -l /dev/input/mice

crw-rw---- 1 root input 13, 63 Dec 28 21:27 /dev/input/miceNamed pipes. can be used to transfer data without having a backing file in disk [21]. For example, we can create a pipe using mkfifo and send some data to it:

$mkfifo my_pipe

$echo "hello world" > my_pipeNote: this will block! Then, in a separate process (e.g. a new terminal window) we can consume that information:

$cat my_pipewhich will also unblock the first process. The named pipe looks like a regular file, but we can see its type:

$ls -l my_pipe

prw-rw-r-- 1 kunigami kunigami 0 Feb 6 10:59 my_pipeSockets. we learned about network sockets in a previous post but sockets are a more general mechanism that can also be used for inter process communication. One example of a socket file is /var/run/dbus/system_bus_socket:

$ls -l /var/run/dbus/system_bus_socket

srw-rw-rw- 1 root root 0 Dec 28 21:27 /var/run/dbus/system_bus_socketFile Permissions

In our previous example rw-rw-r--, every 3 characters represent a level. They are the user, group, and others levels, respectively. user represents the permissions of the owner of the file. group refers to the permission of the group that owns the file (we’ll learn more in section Groups below). Finally others is regarding the permissions from everyone else.

Within each level, the first character represents whether reading is allowed, the second is about writing, the third about executing. Even though they’re displayed as letters, they’re really bits. For example, if reading is allowed, then the first bit is 1 and displayed as r, otherwise it’s 0 and represented as -.

For this reason, a level can be represent be alternatively represented by an octal (0-7), and their binary representation corresponds to the bits that are set. For example rw- is equivalent to 110, which is 6 in octal. This can be handy to succinctly represent the permissions using a 3-digit octal. For example rw-rw-r-- is 664.

We can change the permissions of a file using the chmod command. For example:

$chmod 464 my_file.txtThis has the effect of changing the permissions of my_file.txt to r--rw-r--. Another common operation using chmod is

$chmod +x my_file.txtIt sets (denoted by the + symbol) the execution bit (x) to all levels. There are plenty of different ways to change permissions, which are listed in man chmod.

The permissions when creating regular files is 666 (directories is 777). However, it can be configured by the user. It does so by applying the mask from umask to turn off bits. For example, if we type umask we see:

$umask

002The last digit is the octal of 010, which indicates that we want to turn off the second bit (write) of the third group (others). Another way to see this is by a bitwise operation. Suppose p is a 3-digit octal representing the initial file permission and m the 3-digit octal from umask. The resulting permission can be obtained via ~m & p. We can do the following in Python for example:

>>> p = 0o666

>>> m = 0o002

>>> oct(~m & p)

'0o664'Permission Groups

A user can belong to multiple groups but at any one time, one of the groups is the “active” one. By default the active group has the same name as the user. That’s why when running ls -l in the begining of this section it shows my user name twice:

$ls -l

-rw-rw-r-- 1 kunigami kunigami 43315 Feb 6 09:48 tmp.txtOne can see which groups they belong to by running:

$groups

kunigami adm cdrom sudo dip plugdev lpadmin sambashareThe first group listed is the active group. We can change the active group via newgrp:

$newgrp adm

$rm -f tmp2.txt # make sure the file won't exist

$touch tmp2.txt

$ls -l tmp2.txt

-rw-rw-r-- 1 kunigami admTo change the owner or group of the file, we can use the commands chown (change owner) and chgrp (change group). Worth noting that chown can change groups too.

Special Permission Flags

There are some special bits that can be added to the file. It’s added to the end of the first column in ls -l, so we can tell such bits are set if there are 11 characters in it instead of the usual 10.

The sticky bit mode (t). When this bit is set in a directory, then according to [22]:

… a user can only change files in this directory when she is the user owner of the file or when the file has appropriate permissions. This feature is used on directories like /var/tmp, that have to be accessible for everyone, but where it is not appropriate for users to change or delete each other’s data.

We can verify this bit in /var/tmp:

ls -ld /var/tmp

drwxrwxrwt 9 root root 4096 Jan 5 09:58 /var/tmpThe SUID / SGID - bit (s). On an executable, it will run with the user and group permissions on the file instead of with those of the user issuing the command, thus giving access to system resources. On a directory (group permission only): in this special case every file created in the directory will have the same group owner as the directory itself (while normal behavior would be that new files are owned by the users who create them) [22].

Types of filesystems

Here are some common types of filesystems

EXT Family (Extended filesystem) - These are the usual filesystems used by Linux, and include ext2, ext3 and ext4.

EFI (Extensible Firmware Interface) - EFI is a more general concept which represents a partition on the hard disk used during booting. It is formatted with a filesystem that was originally based on FAT but has its own specification

FAT (File Allocation Table) - Has variants like FAT16, FAT32 - was used by DOS and early versions of Windows

FUSE (Filesystem in Userspace) - It’s a user space filesystem, which means it can be loaded without having priviledges - it provides an interface for user-provided implementations [16].

NTFS (New Technology filesystem) - It’s the default filesystem used by Windows.

SquashFS - Is a read-only filesystem used to compress directories and store them - according to [9], it’s more efficient and flexible than tarball archive.

Tmpfs - This is a special type of filesystem used by the kernel that stores data in memory but adheres to a normal filesystem interface.

One way to get information about the filesystem running in your Linux is via the command df. Here’s a sample of the output I get on a Ubuntu Linux machine:

$df -aT

Filesystem Type Mounted On

/dev/sda5 ext4 /

/dev/sda1 vfat /boot/efi

tmpfs tmpfs /dev/shm

/dev/loop5 squashfs /snap/gnome-calculator/74Note that df doesn’t include the filesystem type by default (needs the option -T) but it has a column named Filesystem which has the entry tmpfs, which happens to also be the type (as we can see for /dev/shm). This can be confusing at first sight.

There are also a bunch of pseudo-filesystems such as sysfs and procfs which are not listed by default, so we need the -a (all) option. The different types of filesystems (including pseudo ones), is in the file /proc/filesystems.

Interesting to note the vfat type on the boot partition, since FAT is mostly associated with Windows. I haven’t found the reasoning behind but it could be so we can have dual operating systems.

We’ll look into what the “mounted on” represents in the next section.

Mount points

A key observation when thinking about the directory tree is that not all subtrees live under the same disk partition. They might be stored in different partitions, different disks, external devices, memory or not be stored at all.

The operation that makes it possible is mounting, which basically appends an entire subtree at a specific path of the directory subtree. Maybe a name with a more vivid analogy would be grafting:

a shoot or twig inserted into a slit on the trunk or stem of a living plant (…).

As we’ll see in Filesystems in the wild, there is a plethora of different mounts under /.

Bind mounts

From [5]:

A bind mount is an alternate view of a directory tree. Classically, mounting creates a view of a storage device as a directory tree. A bind mount instead takes an existing directory tree and replicates it under a different point. The directories and files in the bind mount are the same as the original. Any modification on one side is immediately reflected on the other side, since the two views show the same data.

Bind mounds vs. symlinks. These two concepts look relatively similar, but they have two major differences:

- Symlinks do not work across filesystems

- Binds do not persist any metadata to disk - it’s a in-memory/runtime abstraction

Filesystems in the wild

In this section we present some of the directories and files under /, which are related to the filesystem in some way or are examples of different types of filesystems.

/dev/

This directory corresponds to devices attached to the system.

/dev/hugepages/ - Hugepages is a way for the kernel to allocate pages with sizes much bigger than the default 4k. It’s a mount of the hugetlbfs (pseudo) filesystem. According to [17] Any files created under a directory mounting hugetlbfs uses huge pages

/dev/mqueue/ - stores message queues (used as inter-process communication, ICP) as files. It mounts a pseudo-filesystem called mqueue.

/dev/null - is a character file which discards all the data it receives

/dev/pts - is a mount of the devpts filesystem and is used to store character devices related to the master/slave in pseudoterminal communication [20].

/dev/random - is a character file which provides pseudo-random input

/dev/shm/ - is a mount of tmpfs, used for sharing memory (hence the name shm) between processes [3]. Some programs might use this as a temporary directory to speed things up, since tmpfs is in memory filesystem. More general discussion in [4].

/dev/zero - is a character file which provides 0 (NULL character)

/etc/

This directory contains files that configures parts of the system. The name really mean etcetera and it initially hosted files which didn’t belong into any other directory [10].

/etc/fstab - short for filesystem table, configures how a device (indicated by some ID) should be mounted by default.

/etc/group - contains information about which groups each user belongs to. We’ll cover groups later.

/lost+found/

Is used by fsck (a repair tool) to temporarily store file with corrupted metadata but which might still be useful. fsck can recreate the file metadata but because it doesn’t know where it was originally, it puts in there [6].

/media/

Directory for mounting media such as CD-ROMs and USB sticks [11]

/mnt/

Directory for mounting filesystems temporarily. Both /media/ and /mnt/ are meant for convention because a filesystem can be mounted anywhere in the tree directory, but tools and programs might make assumption on this convention.

/proc/

Directory containing information about processes. It is a mount of the pseudo filesystem called proc(fs). From Wikipedia [12]: The proc filesystem provides a method of communication between kernel space and user space. For example, the GNU version of the process reporting utility ps uses the proc filesystem to obtain its data, without using any specialized system calls.

/proc/filesystems - as described earlier, this file lists the all types of filesystems supported.

/sys/

Directory containing information about kernel processes. It is a mount of a pseudo filesystem called sysfs [13]. From [14]:

For every kobject that is registered with the system, a directory is created for it in sysfs. That directory is created as a subdirectory of the kobject’s parent, expressing internal object hierarchies to userspace. Top-level directories in sysfs represent the common ancestors of object hierarchies; i.e. the subsystems the objects belong to.

/sys/fs/cgroup - cgroup stands for control group which is a way to organize processes hierarchically so properties like access control and limits can be configured in bulk. Not surprisingly, there’s a pseudo filesystem for that purpose, cgroupfs. This path doesn’t have a cgroupfs mount though (mine in tmpfs), but subdirectories like /sys/fs/cgroup/pid do.

/sys/fs/pstore - directory for storing crash logs when the kernel panics. Upon reboot, the OS copies the contents of this directory to another place so the space can be reclaimed. According to [16], this started as a driver under sysfs but evolved into its own filesystem type:

pstore moved from its original firmware driver with a sysfs interface to a more straightforward filesystem-based implementation

/sys/fs/fuse/connections - The default mount point of FUSE filesystems

/sys/kernel/security - The default mount point of the securityfs filesystem, which is an in-memory pseudo file-system intended for secure application [19].

/var/

Variable size files (e.g. logs). Usually stored in a separate disk partition to avoid less important data affecting the main data (for example: avoiding rogue logs from filling up the disk).

Conclusion

I originally intended to write about the Virtual Filesystem from the kernel perspective, mainly looking up to Love’s book Linux Kernel Development but that focuses mostly on the actual C API of the system, and I didn’t have much content for a post.

Instead I decided to write about filesystems from the user perspective and looking up terms and concepts I didn’t know.

I learned a bunch of things I didn’t know through a process of exploration and following through rabbit holes and am relatively happy with the results.

That’s one aspect I like the most in writing posts which is to focus on one topic and try to learn as much as possible in a bounded window of time.

One conclusion from the last section is that not only files are a suitable abstraction for data transportation, but filesystems are a suitable for organizing these file interfaces, as we can see with the vast array of different types of pseudo filesystems.

Related Posts

- Sockets. As discussed in this post, we previously talked about network sockets, which is another case of data transfer (between different machines the network) that is modeled as a file. We can see that in that post where it mentions

socket()returns a file descriptor.

Mentioned by Local Inter-Process Communication.

References

- [1] Introduction to Linux: Chapter 3. About files and the file system

- [2] Linux Kernel Development, by Robert Love

- [3] Chapter 12 Shared Memory Virtual Filesystem

- [4] Superuser: When should I use /dev/shm/ and when should I use /tmp/?

- [5] Unix & Linux: What is a bind mount?

- [6] Unix & Linux: What is the purpose of the lost+found folder in Linux and Unix?

- [7] Unix & Linux: What is a Superblock, Inode, Dentry and a File?

- [8] Unix & Linux: How could Linux use ‘sda’ device file when it hasn’t been installed?

- [9] What is SquashFS

- [10] Linux Directory Structure: /etc Explained

- [11] Wikipedia: Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

- [12] Wikipedia: procfs

- [13] Wikipedia: sysfs

- [14] sysfs - The filesystem for exporting kernel objects

- [15] LWN.net: Persistent storage for a kernel’s “dying breath”

- [16] Github - libfuse/libfuse

- [17] The Linux Kernal Archives: hugetlbpage

- [18] cgroups(7) — Linux manual page

- [19] LWN.net: securityfs

- [20] Wikipedia: devpts

- [21] Wikipedia: Named pipe

- [22] Linuxtopia - 3.4.2.5. Special modes