kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Constructing Trees from a Distance Matrix

Constructing Trees from a Distance Matrix

10 May 2019

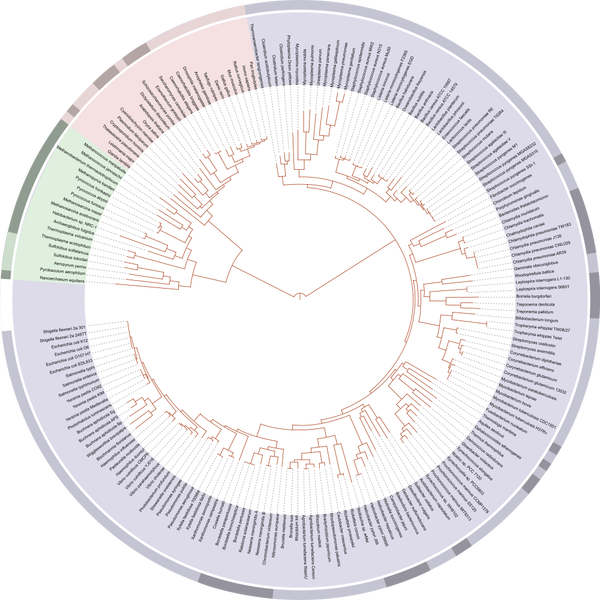

Richard Dawkins is an evolutionary biologist and author of many science books. In The Blind Watchmaker he explains how complex systems can exist without the need of an intelligent design.

Chapter 10 of that book delves into the tree of life. He argues that the tree of life is not arbitrary taxonomy like the classification of animals into kingdoms or families, but it is more like a family tree, where the branching of the tree uniquely describes the true ancestry relationship between the nodes.

Even though we made great strides in genetics and mapped the DNA from several different species, determining the structure of the tree is very difficult. First, we need to define a suitable metric that would encode the ancestry proximity of two species. In other words, if species A evolved into B and C, we need a metric that would lead us to link A-B and A-C but not B-C. Another problem is that internal nodes can be missing (e.g. ancestor species went extinct without fossils).

In this post we’ll deal with a much simpler version of this problem, in which we have the metric well defined, we know the distance between every pair of nodes (perfect information), and all our nodes are leaves, so we have the freedom to decide the internal nodes of the tree.

This simplified problem can be formalized as follows:

Constructing a tree for its distance matrix problem. Suppose we are given a $n \times n$ distance matrix $D$. Construct a tree with $n$ leaves such that the distance between every pair of leaves can be represented by $D$.

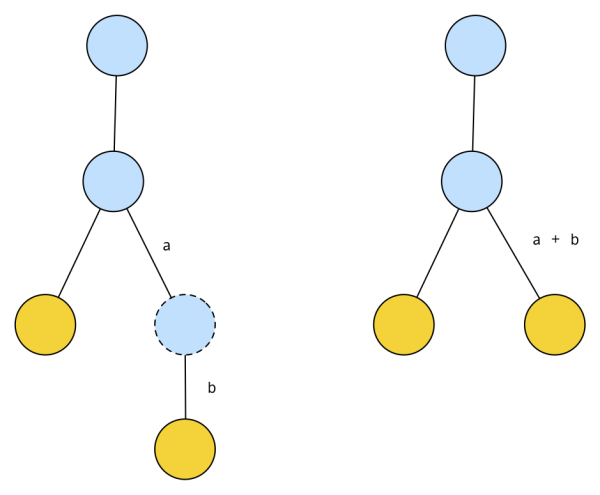

To reduce the amount of possible solutions, we will assume a canonical representation of a tree. A canonical tree doesn’t have any nodes with degree 2. We can always reduce a tree with nodes with degree 2 into a canonical one. For example:

Terminology

Let’s introduce the terminology necessary to define the algorithm for solving our problem. A distance matrix $D$ is a square matrix where $d_{ij}$ represents the distance between elements $i$ and $j$. This matrix is symmetric ($d_{ij} = d_{ji}$), all off-diagonal entries are positive, the diagonal entries are 0, and a triplet $(i, j, k)$ satisfy the triangle inequality, that is,

\[d_{ik} \le d_{ij} + d_{jk}\]A distance matrix is additive if there is a solution to the problem above.

We say two leaves are neighbors if they share a common parent. An edge connecting a leaf to its parent is called limb (edges connecting internal nodes are not limbs).

Deciding whether a matrix is additive

We can decide whether a matrix is additive via the 4-point theorem:

Four-point Theorem. Let D be a distance matrix. If, for every possible set of 4 indexes $(i, j, k, l)$, the following inequality holds (for some permutation):

\[(1) \quad d_{ij} + d_{kl} \le d_{ik} + d_{jl} = d_{il} + d_{jk}\]then D is additive.

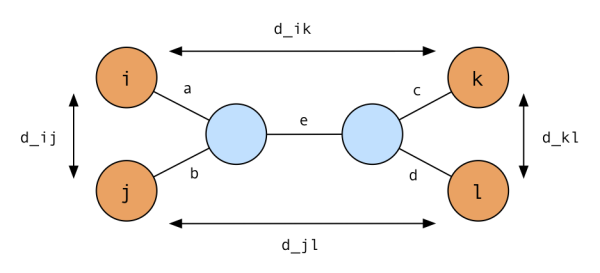

Sketch of proof. We can derive the general idea from the example tree below:

We can see by inspection that (1) is true by inspecting the edges on the path between each pair of leaves. This will be our base case for induction.

Now, we’ll show that if we’re given a distance matrix satisfying (1), we are able to reconstruct a valid tree from it. We have that $d_{ik} = a + e + c$, $d_{jl} = b + e + d$, $d_{ij} = a + b$ and $d_{kl} = c + d$. If we add the first two terms and subtract the last two, we have $d_{ik} + d_{jl} - d_{ij} + d_{kl} = 2e$, so we have

\[e = (d_{ik} + d_{jl} - d_{ij} + d_{kl}) / 2\]We know from (1) that $d_{ik} + d_{jl} \ge d_{kl} + d_{ij} > d_{kl}$, so $e$ is positive.

If we add $d_{ik}$ and $d_{ij}$ and subtract $d_{jl}$, we get $d_{ik} + d_{ij} - d_{jk} = 2a$, so

\[a = (d_{ik} + d_{ij} - d_{jk}) / 2\]To show that $a$ is positive, we need to remember that a distance matrix satisfies the triangle inequality, that is, for any three nodes, $x$, $y$, $z$, $d_{xy} + d_{yz} \ge d_{xz}$. In our case, this means $d_{ij} + d_{jk} \ge d_{ik}$, hence $d_{ij} \ge d_{ik} - d_{jk}$ and a is positive. We can use analogous ideas to derive the values for $b$, $c$ and $d$.

To show this for the more general case, if we can show that for every possible set of 4 leaves $(i, j, k, l)$ this property is held, then we can show there’s a permutation of these four leaves such that the tree from the induced paths between each pair of leaves looks like the specific example we showed above.

For at least one one of these quadruplets, $i$ and $j$ will be neighbors in the reconstructed tree. With the computed values of $a$, $b$, $c$, $d$, $e$, we are able to merge $i$ and $j$ into its parent and generate the distance matrix for $n-1$ leaves, which we can keep doing until $n = 4$. We still need to prove that this modified $n-1 \times n-1$ satisfies the 4-point theorem if and only if the $n \times n$ does.

Limb cutting approach

We’ll see next an algorithm for constructing a tree from an additive matrix.

The general idea is that even though we don’t know the structure of the tree that will “yield” our additive matrix, we are able to determine the length of the limb of any leaf. Knowing that, we can remove the corresponding leaf (and limb) from our unknown tree by removing the corresponding row and column in the distance matrix. We can then solve for the $n-1 \times n-1$ case. Once we have the solution (a tree) for the smaller problem we can “attach” the leaf into the tree.

To compute the limb length and where to attach it, we can rely on the following theorem.

Limb Length Theorem: Given an additive matrix $D$ and a leaf $j$, $\ell_j$ is equal to the minimum of

\[(2) \quad (d_{ij} + d_{jk} - d_{ik})/2\]over all pairs of leaves $i$ and $k$.

The idea behind the theorem is that if we remove the parent of $j$, $p_j$, from the unknown tree, it will divide it into at least 3 subtrees (one being leaf $j$ on its own). This means that there exists leaves $i$ and $k$ that are in different subtrees. This tells us that the path from $i$ to $k$ has to go through $p_j$ and also that the path from $i$ to $j$ and from $j$ to $k$ are disjoint except for $j$’s limb, so we can conclude that:

\[(3) \quad d_{ik} = d_{ij} + d_{jk} - 2 \ell_j\]which yields (2) for $\ell_j$. We can show now that for $i$ and $k$ on the same subtree $d_{ik} \le d_{ij} + d_{jk} - 2*\ell_j$, and hence

\[\ell_j \le (d_{ij} + d_{jk} - d_{ik})/2\]This means that finding the minimum of (2) will satisfy these constraints.

Finding Limb Length: a simple approach to find $\ell_j$ is to, for each $j$, iterate over all $i$ and $k$ and find the minimum of (2), which leads to an $O(n^2)$ algorithm. @balvisio pointed out in the comments that we can solve this in $O(n)$.

Recall that when we remove $p_j$ it will generate 3 trees ($j$, $T_1$ and $T_2$), $i$ will be in one of them, say $T_1$, and it’s possible to show there exists $k$ which is in $T_2$, which automatically satisifes (3).

The idea then is to fix $i \ne j$ and iterate over the other leaves looking for the minimum of (2). While the $k$ we’ll find is not guaranteed to be in $T_2$, but we’re guaranteed to find $k$ satisfying (3).

@balvisio provided the code as well:

def limb_length(d, n, j):

minDistance = float("inf")

i = 1 if j == 0 else j - 1

for k in range(n):

distance = (d[i][j] + d[j][k] - d[i][k])/2

if k != i and k != j and distance < minDistance:

minDistance = distance

return int(minDistance)Attaching leaf j back in. From the argument above, there are at least one pair of leaves $(i, k)$ that yields the minimum $\ell_j$ that belongs to different subtrees when $p_j$ is removed. This means that $p_j$ lies in the path between $i$ and $k$. We need to plug in $j$ at some point on this path such that when computing the distance from $j$ to $i$ and from $j$ to $k$, it will yield $d_{ij}$ and $d_{jk}$ respectively. This might fall in the middle of an edge, in which case we need to create a new node. Note that as long as the edges all have positive values, there’s only one location within the path from $i$ to $k$ that we can attach $j$.

Note: There’s a missing detail in the induction argument here. How can we guarantee that no matter what tree is returned from the inductive step, it is such that attaching $j$ will yield consistent distances from $j$ to all other leaves besides $i$ and $k$?

This constructive proof gives us an algorithm to find a tree for an additive matrix.

Runtime complexity. Finding $\ell_j$ takes $O(n)$. We can generate an $n-1 \times n-1$ matrix in $O(n^2)$ and find the attachment point in $O(n)$. Since each recursive step is proportional to the size of the matrix and we have n such steps, the total runtime complexity is $O(n^3)$.

Detecting non-additive matrices. If we find a non-positive $\ell_j$, this condition is sufficient for a matrix to be considered non-additive, since if we have a corresponding tree we know it has to represent the length of j’s limb. However, is this necessary? It could be that we find a positive value for $\ell_j$ but when trying to attach j back in the distances won’t match.

The answer to this question goes back to the missing detail on the induction step and I don’t know how to answer.

The Neighbor-Joining Algorithm

Naruya Saitou and Masatoshi Nei developed an algorithm, called Neighbor Joining, that also constructs a tree from an additive matrix, but has the additional property that for non-additive ones it serves as heuristic.

The idea behind is simple: It transforms the distance matrix D into another $n \times n$ matrix, $D^*$, such that the minimum non-diagonal entry, say $d_{ij}^*$, in that matrix corresponds to neighboring vertices $(i ,j)$ in the tree, which is generally not true for a distance matrix.

The proof that $D^*$ has this property is non-trivial and will not be provided here. Chapter 7 of [1] has more details and the proof.

Given this property, we can find $i$ and $j$ such that $d^*_{ij}$ is minimal and compute the limbs distances $\ell(i)$ and $\ell_j$, replace them with a single leaf $m$, and solve the problem recursively. With the tree returned by the recursive step we can then attach $i$ and $j$ into $m$, which will become their parents.

Conclusion

In this post we saw how to construct a tree from the distance between its leaves. The algorithms are relatively simple, but proving that they work is not. I got the general idea of the proofs but not 100% of the details.

The idea of reconstructing the genealogical tree of all the species is fascinating and is a very interesting application of graph theory.

References

- [1] Bioinformatics Algorithms: An Active Learning Approach – Compeau, P. and Pevzner P. - Chapter 10

- [2] The Blind Watchmaker - Richard Dawkins