kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Blockchain

Blockchain

05 Nov 2018

Blockchain has become a very popular technology recently due to the spread of Bitcoin. In this post, we’ll focus on the details of blockchain with a focus on Computer Science, studying it as a distributed data structure.

Motivation

Blockchain is a distributed data structure that can be used to implement a distributed ledger system. A distributed ledger orchestrates important operations (for example financial transactions) without the need of a centralized arbiter (such as a financial institution).

The reason to prefer decentralized systems could be from costs of operations: having a few financial institutions mediate all transactions require a lot of work; To avoid a single point of failure (more reliable), and finally to not have to trust a few companies with our assets.

Additionally, by being decentralized, the expectation is that it becomes less likely to regulate and thus far it has enable global currencies like bitcoin.

Challenges

The main challenge with a distributed ledger is how to distribute the work and data across nodes in a network and, more importantly, how to make sure we can trust that information.

An initial naive idea could be to store a copy of all accounts balances in every node of the network. The problem of storing only the balances of accounts is that it’s very hard to verify whether a given payment went through or make sure the balances are consistent. To address that, the blockchain also stores the whole history of transactions that led to the current balances (think of version control).

Safety. Even if we have the whole history of the transactions, it’s possible for a bad actor to tamper with this history on their own benefit, so we need a safety mechanism to prevent that.

Consistency. Finally, because we store copies of data that is changing all the time in multiple machines, we’ll invariably hit problems with consistency and sources of truth.

Blockchain is a data structure designed to address these challenges as we shall see next. We’ll use bitcoin as the application when describing examples.

Data Structure

A blockchain is a chain of entities called blocks that is replicated to several nodes in a network. Each block has a hash which is computed as a function of its contents and the hash of the previous node in the chain.

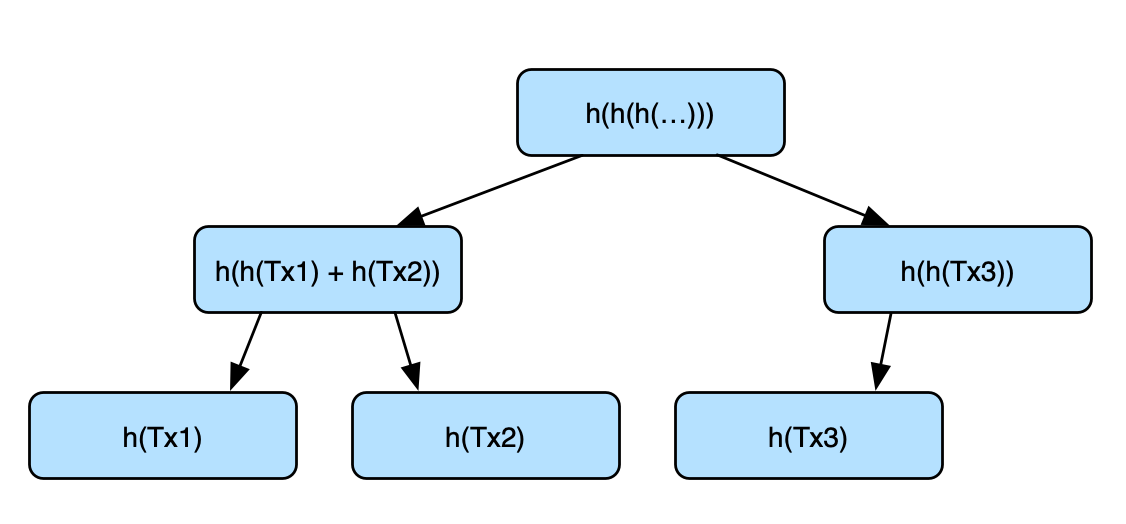

For the bitcoin case, the content of the block is a set of transactions adding up to 1MB. The hash of the contents is the hash of the combination of the hashes of individual transactions. More specifically, these hashes can be organized in a binary tree (also known as Merkle Tree) where the transactions hashes are the leaves and the hashes of individual inner nodes are the hash of the concatenation of the hashes of the children.

Source of truth. There might be several different versions of the chain around the network, either due to inconsistency or bad actors. The assumption is that the chain with most nodes that is agreed upon by the majority of the nodes (over 50%) is the accurate and most up-to-date version of the chain and the one that should be trusted.

Inserting Blocks

The insertion consists of adding a new transaction to the blockchain. In terms of our bitcoin example, this is essentially user A sending some amount of money to user B.

To start the process, node A broadcasts a message with the transaction, signing it with its private key. The other nodes on the network have node A’s public key, so they can check the authenticity of the transaction.

The transaction stays in a pool of unresolved transactions. At any time, there are many nodes in the network constructing a new block, which contains several transactions. These nodes are also called miners. Not all nodes in the network need to be miners. Note that each block can pick any transaction from the pool so the set of transactions in a block under construction can be different between miners.

Adding a transaction to its block consists of verifying things like its authenticity, the validity (e.g. to make sure there are enough funds to be spend), then inserting it to the Merkle Tree, which allows recomputing the root hash in O(log n) time.

Each block should be around 1MB in size, so when a miner is done collecting enough transactions it can start wrapping up its work. It needs to compute the block hash which is a string such that when concatenated with the Merkle tree root hash and the previous block in the largest chain will generate a hash with k leading 0s. Since the hash function used is cryptographic, it cannot be easily reverse-engineered. The only way to find such string is via brute force. The number k is a parameter that determines the difficulty in finding the hash (the value is controlled by some central authority but rarely changes). The idea of this hash computation is that it’s purposely a CPU-expensive operation, so that it’s too costly for attackers to forge hashes as we’ll see later.

Once it finds the hash, it can broadcast the new block to the network where other miners can start to validate this block. They can check that:

- The transactions in the block are valid

- The block was added to the largest chain known

- The hash generated for the block is correct The verification step should be much cheaper than the process of generating the hash. Once the block passes the validation, the miner adds it to the largest chain. Now, when there’s a call to get the largest chain, this last block will be included. On the other hand, if any of the validation steps failed, the block is rejected.

Because of this, miners building their blocks can also periodically check for updates in the network for larger chains. If, while they’re building their blocks or computing the hash a new larger chain arrives, it’s better to start over, since it will be rejected later anyway.

Checking for valid transactions

In the bitcoin example, suppose I’m a vendor and I want to verify that your payment to me went through before I ship you my product.

To check whether a transaction was validated, a node just needs to ask for the current longest blockchain, which is the source of truth, and see if the transaction appears in any of the blocks.

Double-Spending

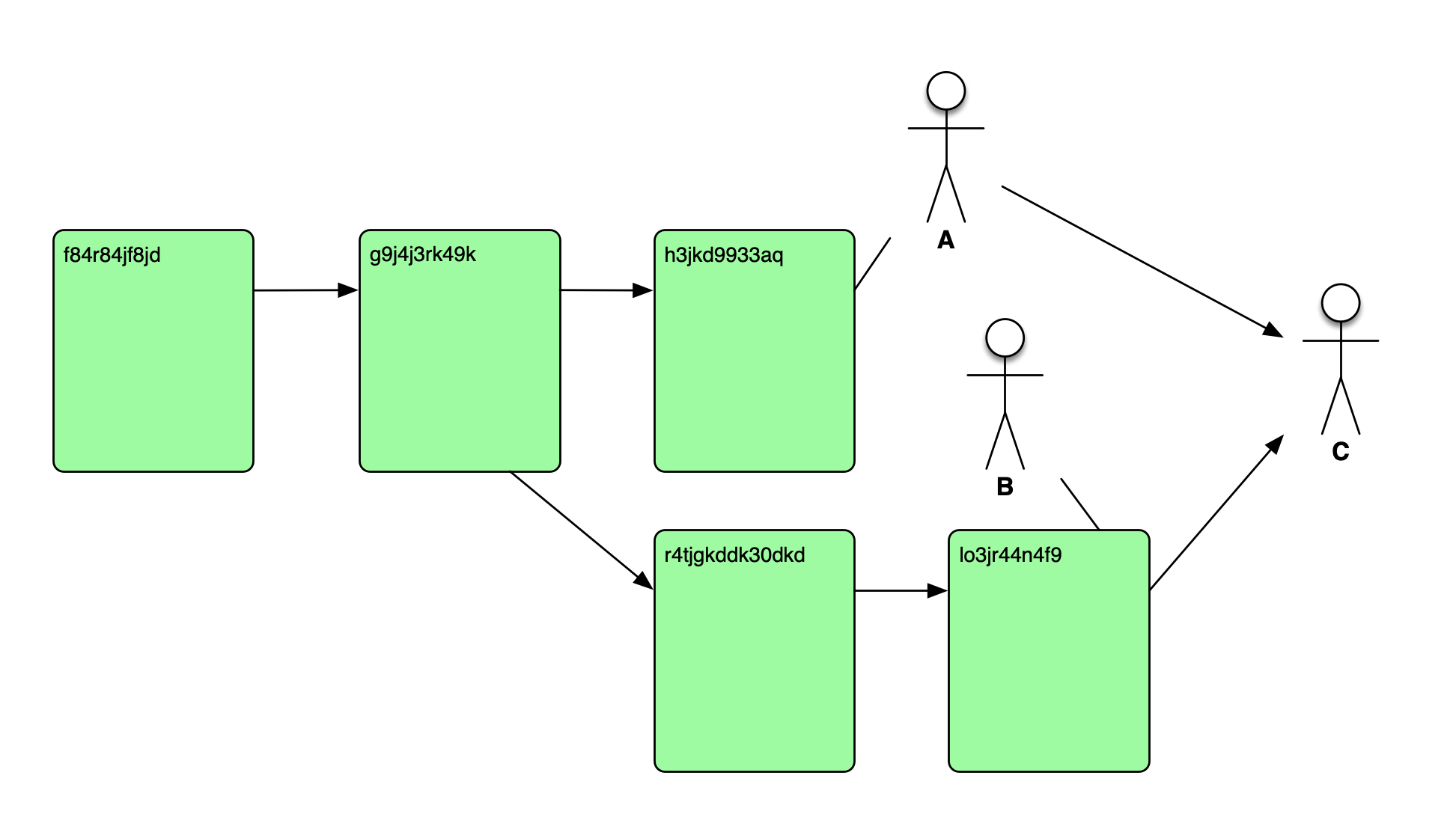

Say user A has exactly 1 coin, and that it sends to B as payment. Immediately after, A sends that same coin to another user C. How does C make sure that the coin it’s receiving is not spent before?

In a decentralized ledger, this could lead to problems since different nodes could disagree to where the coin went. In the blockchain, there are two scenarios:

- A to B got included in a block first which later became part of the longest chain (and hence the source of truth). The transaction from A to C would be rejected from being added to future blocks due to insufficient funds.

- A to B and A to C got picked up to be included in the same block. The miner constructing the block would consider the second transaction it picked up invalid. Even if it was malicious and it included both transactions, it would fail validation when broadcasting it to the network. The case in which A to C gets picked up first is analogous.

Changing History

Suppose that user A, after performing a payment to and receiving its product from user B, wants to reuse the transaction and send the money to another user C. In theory it could edit the destination of the transaction from the chain (or even replace the block entirely), but to make this modified chain become the source of truth, it would also need to make it the longest.

As we’ve seen above, adding a block to a chain with a valid hash is extremely expensive. To make it the new source of truth, it would need to add at least one block in addition to the forged one. This means it would need to outpace all the other miners in the network that are also continuously computing new blocks in parallel. The paper [1] claims that unless the attacker controls over 50% of the CPU power in the network, this is extremely unlikely to succeed.

Note that a user cannot modify the transactions it is not the sender of, since a transaction from user A to user B is signed with A’s private key. If user C wanted to redirect A’s money to itself, it would need to know A’s private key, so it could sign the transaction pretending it’s A.

Incentives

As we mentioned earlier, not all nodes in the network need to be miners. So why would any node volunteer to spend energy in form of CPU cycles to compute hashes? In bitcoin, the incentive is that the miner whose block gets added to the chain receives bitcoins as reward. These bitcoins are collected as fees from the normal transactions.

There must incentives to make sure that a miner won’t keep building blocks with one or zero transactions, to skip doing any validations for transactions. The reward should take into account the transaction, and possibly its value and their age (to make sure “unimportant” transactions won’t be ignored forever).

Conclusion

In researching the material for this post, I ran into a lot of articles and videos covering blockchain without going into much detail. As always, I only realized my understanding had a lot of gaps once I started writing this post.

Overall I know a good deal more about what Blockchain is and what it’s not. I’m curious to see what other applications will make use of this technology and if we can come up with a trustworthy system that doesn’t require wasting a lot of CPU power.

References

- [1] Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System

- [2] Hashcash: A Denial of Service Counter-Measure - A proof-of-work algorithm

- [3] Blockchain: how mining works and transactions are processed in seven steps

- [4] Bitcoin P2P e-cash paper - The proof-of-work chain is a solution to the Byzantine Generals’ Problem