kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Bulls and Cows

Bulls and Cows

04 Jun 2018

Bulls and Cows (also known as MOO) is a 2-player game in which one player comes up with a secret and the other has to guess the secret. The secret consists of 4 digits from 0 to 9, where each digit is distinct. Player 2 has to guess these 4 digits, in the right order. At each guess from player 2, player 1 provides feedback as hints. The hints are two numbers: one telling how many digits from the secret player 2 got in the right order (bull), and another telling how many digits they got but in the wrong order (cow).

For example, if player 1 came up with 4271, and player 2 guessed 1234, then bull is 1 (digit 2), and cow is 2 (1 and 4 are in the secret, but not in the order guessed by player 2).

The goal of the game is for player 2 to guess the secret with the least amount of guesses.

In this post we’ll present computational experiments to solve a game of Bulls and Cows optimally.

Objective function

We’ll focus on a search strategy to minimize the maximum number of guesses one has to make, for any possible secret (see caveat in the next section). Alternatively, John Francis’s paper [1] proposes heuristics that minimize the expected number of guesses, that is, for the worst case these heuristics might not be optimal, but they perform better on average.

Because the game has turns, our solution is not a single list of guesses, but rather a decision tree where at each node we branch depending on the hint we get back. The metric we are trying to optimize is then the height of such tree.

To break ties between trees of the same height, we consider the smallest tree (the one with least nodes).

Brute-force search

Our search algorithm is recursive. At any given recursion level, we are given a set containing all possible numbers that could be secrets. We’ll try all combinations of guesses and hints and see which ones yield the best solution.

When we simulate a given guess and hint, we are restricting the possible numbers that can still be secret, so in the next level of recursion, the set of potential secrets will be smaller. Caveat: as @Innoble points out in the comments, this restriction might lead to suboptimal solutions, so this brute-force search is solving a restricted version of the problem.

For example, say that the possible secrets are any 4-digit number with no repeated digits. We then use one of them as a guess, say, [0, 1, 2, 3]. One possible hint we could receive is (3, 0). What are the possible secrets that would cause us to receive this hint? [0, 1, 2, 4], [0, 1, 2, 5] and [7, 1, 2, 3] are a few of those. If we recurse for this guess and hint, the set of secrets in the next level will be restricted to those that would return a hint (3, 0) for [0, 1, 2, 3].

Continuing our example, is [0, 1, 2, 3] the best guess we can make at that point? After recursing for all possible hints, we’ll have a decision tree rooted on [0, 1, 2, 3]. The key idea of the search is that we can minimize the height of the final decision tree by minimizing the subtrees at each recursion level (greedy strategy). Thus, we want to find the guess with the shortest subtree.

In pseudo-code code, the search looks like this:

def search(possible_secrets):

for guess in possible_secrets:

for each hint:

new_possible_secrets # possible_secrets that would return hint for 'guess'

decision_subtree = search(new_possible_secrets)

if height(decision_subree) < height(best_subtree):

best_decision_subtree = decision_subree

best_guess = guess

return {guess: best_guess, subtree: best_decision_subtree}We start with all possible secrets (4-digit number with no repeated digits) and the tree returned should be optimal in minimizing the number of guesses for the worst case.

Rust implementation

I initially implemented the search in Python, but it was taking too long, even when artificially restricting the branching. I re-implemented it in Rust and saw some 20x speedups (caveat: I haven’t really tried to optimize the Python version).

The main difference between the pseudo-code and the actual implementation is that we pre-group possible_secrets by their hint for guess, which is more efficient than scanning possible_secrets for all possible hints:

fn group_possibilities_by_score(

guess: &[i32; N],

possibilities: &Vec<[i32; N]>

) -> [Vec<[i32; N]>; NN] {

let mut possibilities_by_score: [Vec<[i32; N]>; NN] = Default::default();

for i in 0..NN {

possibilities_by_score[i] = vec![];

}

for possibility in possibilities {

let mut new_possibility = possibility.clone();

let score = compute_score(&guess, &new_possibility);

let score_index = encode_score(score);

possibilities_by_score[score_index].push(new_possibility)

}

return possibilities_by_score;

}

fn compute_score(guess: &[i32; N], secret: &[i32; N]) -> (i32, i32) {

let mut perfect_matches = 0;

for i in 0..guess.len() {

if guess[i] == secret[i] {

perfect_matches += 1;

}

}

let mut look_up_position: [bool; D] = [false; D];

for i in 0..guess.len() {

let position = (guess[i] - 1) as usize;

look_up_position[position] = true;

}

let mut any_matches = 0;

for i in 0..secret.len() {

let position = (secret[i] - 1) as usize;

if look_up_position[position] {

any_matches += 1;

}

}

let imperfect_matches = any_matches - perfect_matches;

return (perfect_matches, imperfect_matches);

}

fn encode_score(score: (i32, i32)) -> usize {

let n = (N + 1) as i32;

return (score.0 * n + score.1) as usize;

}The function group_possibilities_by_score() above makes use of compute_score and it also uses a fixed-length array for performance. The set of hints is proportional to the squared size N of the guess, in our case N=4.

Turns out that the Rust implementation is still not efficient enough, so we’ll need further optimizations.

Optimization - Classes of Equivalence

What is a good first guess? It doesn’t matter! We don’t have any prior information about the secret and every valid number is equality probable. For example, if we guess [0, 1, 2, 3] or [5, 1, 8, 7], the height of the decision tree will be the same. An intuitive way to see why this is the case is that we could relabel the digits such that [5, 1, 8, 7] would map to [0, 1, 2, 3].

Francis [1] generalizes this idea for other cases. Say that at a given point we made guesses covering the digits 0, 6, 7, 8 and 9 at least once. Now say we our next guess is [0, 8, 9, 3]. In here, 3 is the only digit we haven’t tried yet, but using the re-labeling argument, we can see that [0, 8, 9, 1] would yield the same decision tree if we were to swap the labels of 1 and 3. This allow us to skip guesses that belong to the same class, which reduces the branch factor.

We can generate an ID representing a given class. A way to do this is by adding one to each digit we have tried before and making any digit we haven’t as 0, then converting that number from base 11 to base 10. For example, [0, 8, 9, 1] becomes [1, 9, 10, 0]. If this was a number in base 11, in base 10 it is 2530 ((((1*11) + 9)*11 + 10)*11 + 0). If we do the same with [0, 8, 9, 3], we’ll get the same number. The code below implements this idea.

fn get_class(visited_bits: u32, guess: &[i32; N]) -> i32 {

let mut class_id = 0;

let mut multiplier: i32 = 1;

let d = (D + 1) as i32;

for pos in 0..guess.len() {

let digit = guess[pos];

if visited_bits & (1 << digit) != 0 {

class_id += multiplier * (digit + 1);

}

multiplier *= d;

}

return class_id;

}In our case, D = 10 and we store the set of visited digits in a bitset, visited_bits (that is, bit i is 1 if digit i has been visited.

On the search side, we keep a set of classes ids already visited and skip a guess if its class is already in there.

let mut visited_classes = HashMap::new();

for guess in &possibilities {

let class_id = get_class(visited_bits, guess);

// Same equivalence class. Won't yield new results

if visited_classes.contains_key(&class_id) {

continue;

}

visited_classes.insert(class_id, true);

// Search continues...

}With this optimization the search algorithm runs in under 2 minutes. By inspecting the height of the resulting tree we conclude that the minimum number of guesses necessary for any secret is 7.

The complete code is available on Github.

Visualizing

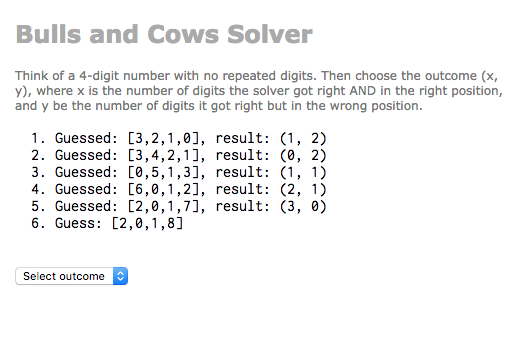

The JSON output by the search algorithm is quite big (the smallest tree with height 7 has almost 7000 nodes). A more interesting way to inspect the data is to create a Bulls and Cows solver. We feed the JSON to this application and ask the user to select the outcome based on the secret they have in mind. We are basically traversing the edges of the decision tree.

I’ve uploaded the application to my personal website and the source code is available on Github.

Conclusion

I learned about this game pretty recently and was curious to learn of good strategies to solve this problem. From what I’ve been reading, the heuristics that yield good solutions are very complicated for a human to perform. This leads to an question: is there are any solution which is simple to follow but that is reasonably good?

One natural extension for this problem is to use larger numbers of digits (N > 4) and have each element be sourced from 0 to D - 1. An exhaustive search might be prohibitive, but maybe we can come up with heuristics with constant guarantees. What is a lower bound for the number of guesses for variants with arbitrary N and D?

I struggled to implement this code in Rust, but I found the challenge worthwhile. I learned a bit more about its specifics, especially regarding memory management and data types.