kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Numerical Representations as inspiration for Data Structures

Numerical Representations as inspiration for Data Structures

01 Sep 2017

In this chapter Okasaki describes a technique for developing efficient data structures through analogies with numerical representations, in particular the binary and its variations.

We’ve seen this pattern arise with Binomial Heaps in the past. Here the author presents the technique in its general form and applies it to another data structure, binary random access lists.

Binary Random Access Lists

These lists allows efficient insertion at/removal from the beginning, and also access and update at a particular index.

The simple version of this structure consists in distributing the elements in complete binary leaf trees. A complete binary leaf tree (CBLF) is one that only stores elements only at the leaves, so a tree with height i, has 2^(i+1)-1 nodes, but only 2^i elements.

Consider an array of size n, and let Bn be the binary representation of n. If the i-th digit of Bn is 1, then we have a tree containing 2^i leaves. We then distribute the elements into these trees, starting with the least significant digit (i.e. the smallest tree) and traversing the tree in

pre-order.

For example, an array of elements (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11) has 11 elements, which is 1011 in binary. So we have one tree with a single leave (1), a tree with 2 leaves (2, 3) and another containing 8 leaves (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11).

We use a dense representation of the binary number, by having explicit elements for the 0 digit. Here’s a possible signature for this implementation:

type 'a tree = Leaf of 'a | Node of {

size: int; (* Number of elements/leaves in the tree - not nodes *)

left: 'a tree; (* left sub-tree *)

right: 'a tree; (* right sub-tree *)

};;

(* Binary representation of the list *)

type 'a digit = Zero | One of 'a tree;;

type 'a t = 'a digit list;;Inserting a new element consists in adding a new tree with a single leave. If a tree already exists for a given size, they have to be merged into a tree of the next index. Merging two CBLFs of the same size is straightforward. We just need to make them children of a new root. Since elements are stored in pre-order, the tree being inserted or coming from carry over should be the left child.

Looping back to our example, if we want to insert the element 100, we first insert a tree with a single leaf (100). Since the least significant digit already has an element, we need to merge them into a new tree containing (100, 1) and try to insert at the next position. A conflict will arise with (2, 3), so we again merge them into (100, 1, 2, 3) and try the next position. We finally succeed in inserting at position 2, for a new list containing trees like (100, 1, 2, 3) and (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11).

The complexity of inserting an element is O(log n) in the worst case which requires merging tree for all digits (e.g. if Bn = 111...111). Merging two trees is O(1).

let size tree = match tree with

| Leaf _ -> 1

| Node ({size}) -> size

;;

let link tree1 tree2 = Node {

size = (size tree1) + (size tree2);

left = tree1;

right = tree2;

};;

let rec pushTree tree digits = match digits with

| [] -> [One tree]

| Zero :: restDigits -> (One tree) :: restDigits

| (One currentTree) :: restDigits ->

Zero :: (pushTree (link tree currentTree) restDigits)

;;

let push element digits = pushTree (Leaf element) digits;;Removing the first element is analogous to decrementing the number, borrowing from the next digit if the current digit is 0.

Searching for an index consists in first finding the tree containing the index and then searching within the tree. More specifically, because the elements are sorted beginning from the smallest tree to the largest, we can find the right tree just by inspecting the number of elements in each tree until we find the one whose range includes the desired index. Within a tree, elements are stored in pre-order, so we can find the right index in O(height) of the tree.

After finding the right index, returning the element at that index is trivial. Updating the element at a given index requires rebuilding the tree when returning from the recursive calls.

let rec updateTree index element tree = match tree with

| Leaf _ ->

if index == 0 then (Leaf element) else raise IndexOutOfBoundsException

| (Node {size; left; right}) -> if index < size / 2

then Node {size; left = updateTree index element left; right}

else Node {

size;

left;

right = updateTree (index - size / 2) element right;

}

;;

let rec update index element digits = match digits with

| [] -> raise IndexOutOfBoundsException

| Zero :: restDigits -> Zero :: (update index element restDigits)

| (One tree) :: restDigits ->

if index < size tree

then (One (updateTree index element tree)) :: restDigits

else (One tree) :: (update (index - (size tree)) element restDigits)

;;Okasaki then proposes a few different numbering systems that allow to perform insertion/removal in O(1) time. Here we’ll only discuss the less obvious but more elegant one, using skew binary numbers.

Skew Binary Random Access Lists

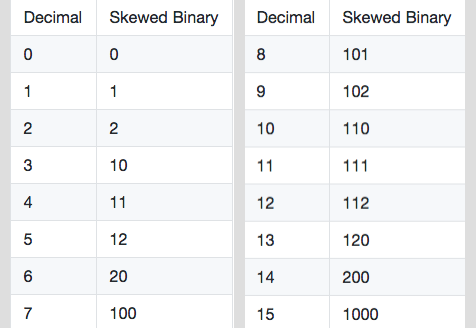

A skew binary number representation supports the digits 0, 1 and 2.

The weight of the i-th digit is 2^(i+1) - 1. In its canonical form, it only allows the least significant non-zero digit to be 2.

Examples:

It’s possible to show this number system offers a unique representation for decimal numbers. See the Appendix for a sketch of the proof and an algorithm for converting decimals to skewed binary numbers.

Incrementing a number follows these rules:

- If there’s a digit 2 in the number, turn it into 0 and increment the next digit. By definition that is either 0 or 1, so we can safely increment it without having to continue carrying over.

- Otherwise the least significant digit is either 0 or 1, and it can be incremented without carry overs.

The advantage of this number system is that increments (similarly, decrements) never carry over more than once so the complexity

O(1), as opposed to the worst-caseO(log n)for regular binary numbers.

A skew binary random access list can be implemented using this idea. We use a sparse representation (that is, not including 0s). Each digit one with position i corresponds to a tree with (2^(i+1) - 1) elements, in this case a complete binary tree with height i+1. A digit 2 is represented by two consecutive trees

with same weight.

type 'a node = Leaf of 'a | Node of {

element: 'a;

left: 'a node; (* left sub-tree *)

right: 'a node; (* right sub-tree *)

};;

type 'a tree = {size: int; tree: 'a node};;

type 'a t = 'a tree list;;Adding a new element to the beginning of the list is analogous to incrementing the number, which we saw can be done in O(1). Converting a digit 0 to 1 or 1 to 2, is a matter of prepending a tree to a list. To convert a 2 to 0 and increment the next position, we need to merge two trees representing it with the element to be inserted. Because each tree is traversed in pre-order, we make the element the root of the tree.

let push element ls = match ls with

| {size = size1; tree = tree1} ::

{size = size2; tree = tree2} ::

rest -> if size1 == size2 (* First non-zero digit is 2 *)

then {

size = 1 + size1 + size2;

tree = Node {element; left = tree1; right = tree2}

} :: rest

(* Add a tree of size 1 to the beginning, analogous to converting a

digit 0 to 1, or 1 to 2 *)

else {size = 1; tree = Leaf element} :: ls

| _ -> {size = 1; tree = Leaf element} :: ls

;;Elements are inserted in pre-order in each tree, so when searching for an

index, we can first find the right tree by looking at the tree sizes and within a tree we can do a “binary search” in O(height) of the tree.

let rec updateTree index newElement tree size = match tree with

| Leaf element -> Leaf newElement

| Node {element; left; right} ->

let newSize = ((size + 1) / 2) - 1 in

if index == 0 then Node {element = newElement; left; right}

else if index <= newSize then

Node {

element;

left = updateTree (index - 1) newElement left newSize;

right;

}

else

Node {

element;

left;

right = updateTree (index - newSize - 1) newElement right newSize;

}

;;

let rec update index element ls = match ls with

| [] -> raise IndexOutOfBoundsException

| {size; tree} :: rest -> if index < size

then {size; tree = updateTree index element tree size} :: rest

else {size; tree} :: (update (index - size) element rest)

;;Binomial Heaps

In this chapter, this technique is also applied to improve the worst case runtime of insertion of binomial heaps. The implementation, named Skewed Binomial Heap, is on github.

Conclusion

This chapter demonstrated that binary representations are a useful analogy to come up with data structures and algorithms, because they’re simple. This simplicity can lead to inefficient running times, though. Representations such as skewed binary numbers can improve the worst case of some operations with the trade-off of less intuitive and more complex implementations.

Appendix A - Proof

Sketch of the proof. First, it’s obvious that two different decimals cannot map to the same binary representation. Otherwise the same equation with the same weights would result in different values. We need to show that two binary representations do not map to the same decimal.

Suppose it does, and let them be B1 and B2. Let k be the largest position where these number have a different digit. Without loss of generality, suppose that B1[k] > B2[k].

First case. suppose that B1[k] = 1, and B2[k] = 0 and B2 doesn’t have any digit 2. B1 is then at least \(M + 2^{k+1} - 1\), while B2 is at most \(M + \sum_{i = 1}^{k} (2^{i} - 1)\) which is \(M + 2^{k + 1} - k\) (M corresponds to the total weight of digits in positions > k). This implies that B2 < B1, a contradiction.

Second case. suppose that B1[k] = 1, but now B2 does have a digit 2 at position j. It has to be that j < k. Since only zeros follow it, we can write B2’s upper bound as

Since \(2(2^{j + 1} - 1) < 2^{j + 2} - 1\), we have

\[\sum_{i = j + 1}^{k} (2^{i} - 1) + 2^{j + 1} - 1 < \sum_{i = j + 2}^{k} (2^{i} - 1) + 2^{j + 2} - 1\]We can continue this argument until we get that B2 is less than \(M + 2(2^{k} - 1)\) which is less than \(M + 2^{k + 1} - 1\), B1.

Third case. Finally, suppose we have B1' such that B1'[k] = 2, and B2'[k] = 1. We can subtract \(2^{k+1} - 1\) from both and reduce to the previous case. ▢

Appendix B - Conversion algorithm

Converting from a decimal representation to a binary one is straightforward, but it’s more involved to do so for skewed binary numbers.

Suppose we allow trailing zeros and have all the numbers with k-digits. For example, if k=2, we have 00, 01, 02, 10, 11, 12 and 20. We can construct the numbers with k+1-digits by either prefixing 0 or 1, and the additional 2 followed by k zeros. For k=3, we have 000, 001, 002, 010, 011, 012, 020, 100, 101, 102, 110, 111, 112, 120 and finally 200.

More generally, we can see there are 2^(k+1) - 1 numbers with k digits. We can construct the k+1 digits by appending 0 or 1 and then adding an extra number which is starts 2 and is followed by k zeros, for a total of 2^(k+1) - 1 + 2^(k+1) - 1 + 1 = 2^(k + 2) - 1, so we can see this invariant holds by induction on k, and we verify that is true for the base, since for k = 1 we enumerated 3 numbers.

This gives us a method to construct the skewed number representation if we know the number of its digits say, k. If the number is the first 2^(k) - 1 numbers, that is, between 0 and 2^k - 2, we know it starts with a 0. If it’s the next 2^(k) - 1, that is, between 2^k - 1 and 2^(k+1) - 3, we know it starts with a 1. If it’s the next one, exactly 2^(k+1) - 2, we know it starts with a 2.

We can continue recursively by subtracting the corresponding weight for this digit until k = 0. We can find out how many digits a number n has (if we’re to exclude leading zeros) by find the smallest k such that 2^(k+1)-1 is greater than n. For example, for 8, the smallest k is 3, since 2^(k+1)-1 = 15, and 2^(k)-1 = 7.

The Python code below uses these ideas to find the skewed binary number representation in O(log n):

def decimalToSkewedBinaryInner (n, weight):

if n < weight:

return (n, [])

else:

rest, skewDigits = decimalToSkewedBinaryInner(n, 2*weight + 1)

if rest == 2*weight :

return (0, skewDigits + [2])

elif rest >= weight :

return (rest - weight, skewDigits + [1])

else:

return (rest, skewDigits + [0])

def decimalToSkewedBinary (n):

if n == 0:

return [0]

remainder, digits = decimalToSkewedBinaryInner(n, 1)

assert remainder == 0

return digitsOne might ask: why not OCaml? My excuse is that I already have a number theory repository in Python, so it seemed like a nice addition. Converting this to functional code, in particular OCaml is easy.

This algorithm requires an additional O(log n) memory, while the conversion to a binary number can be done with constant extra memory. My intuition is that this is possible because the weights for the binary numbers are powers of the same number, 2^k, unlike the skewed numbers’ weights. Is it possible to work around this?