kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Largest sets of subsequences in OCaml

Largest sets of subsequences in OCaml

22 May 2017

I’ve noticed that there is this set of words in English that look very similar: tough, though, through, thought, thorough, through and trough. Except thought, they have one property in common: they’re all subsequence of thorough. It made me wonder if there are interesting sets of words that are subsequences of other words.

This post is an attempt to answer a more general question: given a list of words, what is the largest set of these words such that they’re subsequences of a given word?

A word A is a subsequence of a word B if A can be obtained by removing zero or more characters from B. For example, “ac” is a subsequence of “abc”, so is “bc” and even “abc”, but not “ba” nor “aa”.

A simple algorithm to determine if a word A is a subsequence of another is to start with 2 pointers at the beginning of each word, pA and pB. We move pB forward until pA and pB point to the same character. In that case we move pA forward. A is a subsequence of B if and only if we reach the end of A before B. We could then iterate over each word W and find all the words that are subsequences of W. If the size of the dictionary is n, and the size of the largest word is w, this algorithm would run in \(O(n^2 w)\).

For English words, we can use entries from /usr/share/dict/words. In this case, n is around 235k (wc -l /usr/share/dict/words), so a quadratic algorithm will take a while to run (around 5e10 operations).

Another approach is to generate all subsequences of words for a given word W and search the dictionary for the generated word. There are \(O(2^w)\) subsequences of a word of length \(w\). If we use a hash table, we can then do it in \(O(n w 2^w)\). In /usr/share/dict/words, the length of the largest word, w, is 24.

Running a calculation with the numbers (R script), the number of high-level operations is 4e10, about the same order of magnitude as the quadratic algorithm.

A third approach is to use a trie. This data structure allows us to store the words from the dictionary in a space-efficient way and we can search for all subsequences using this structure. The trie will have at most 2e6 characters (sum of characters of all words), less because of shared prefixes. Since any valid subsequence has to be a node in the trie, the cost of search for a given word cannot be more than the size of the trie t, so the complexity per word is \(O(\min(2^w, t))\). A back of envelope calculation gives us 2e9. But we’re hoping that the size of the trie will be much less than 2e6.

Before implementing the algorithm, let’s define out trie data structure.

The Trie data structure

A trie is a tree where each node has up to |E| children, where |E| is the size of the alphabet in consideration. For this problem, we’ll use lower case ascii only, so it’s 26. The node has also a flag telling whether there’s a word ending at this node.

module ChildList = Map.Make(Char);;

(*

Fields:

1. Map of chars to child nodes

2. Whether this node represent a word

*)

type trie = Node of trie ChildList.t * bool;;Notice that in this implementation of trie, the character is in the edge of the trie, not in the node. The Map structure from the stlib uses a tree underneath so get and set operations are \(O(log \mid E \mid)\).

The insertion is the core method of the structure. At a given node we have a string we want to insert. We look at the first character of the word. If a corresponding edge exists, we keep following down that path. If not, we first create a new node.

let rec insert (s: char list) (trie: trie) : trie =

let Node(children, hasEntry) = trie in match s with

| [] -> Node(children, true)

| first_char :: rest ->

let currentChild = if ChildList.mem first_char children

then (ChildList.find first_char children)

else empty

in

let newChild = insert rest currentChild in

let newChildren = ChildList.add first_char newChild children in

Node(

newChildren,

hasEntry

)

;;To decide whether a trie has a given string, we just need to traverse the trie until we either can’t find an edge to follow or after reaching the end node it doesn’t have the hasEntry flag set to true:

let rec has (s: char list) (trie: trie): bool =

let Node(children, hasEntry) = trie in match s with

| [] -> hasEntry

| first_char :: rest ->

if ChildList.mem first_char children then

has rest (ChildList.find first_char children)

else false

;;This and other trie methods are available on github.

The search algorithm

Given a word W, we can search for all its subsequences in a trie with the following recursive algorithm: given a trie and a string we perform two searches: 1) for all the subsequences that contain the first character of current string, in which case we “consume” the first character and follow the corresponding node and 2) for all the subsequences that do not contain the first character of the current string, in which case we “consume” the character but stay at the current node. In pseudo-code:

Search(t: TrieNode, w: string):

Let c be the first character of w.

Let wrest be w with the first character removed

If t contains a word, it's a subsequence of the

original word. Save it.

// Pick character c

Search(t->child[c], wrest)

// Do not pick character c

Search(t, wrest)The implementation in OCaml is given below:

(* Search for all subsequences of s in a trie *)

let rec searchSubsequenceImpl

(s: char list)

(trie: trie)

: char list list = match s with

| [] -> []

| first_char :: rest_s ->

let Node(children, _) = trie in

(* Branch 1: Pick character *)

let withChar = if Trie.ChildList.mem first_char children

then

let nextNode = Trie.ChildList.find first_char children in

let matches = searchSubsequenceImpl rest_s nextNode in

let Node(_, next_is_word) = nextNode in

let fullMatches = if next_is_word then ([] :: matches) else matches in

(* Add the current matching character to all matches *)

List.map (fun word -> first_char :: word) fullMatches

else []

in

(* Branch 2: Do not pick character *)

let withoutChar = searchSubsequenceImpl rest_s trie

in

(* Merge results *)

withChar @ withoutChar

let searchSubsequence (s: string) (trie: trie): string list =

let chars = BatString.to_list s in

let results = searchSubsequenceImpl chars trie in

List.map BatString.of_list results |> removeDuplicatesExperiments

Our experiment consists in loading the words from /usr/share/dict/words into a trie, and then, for each word in the dictionary, look for its subsequences. The full code is available on github.

The code takes 90 seconds to run on my laptop. Not too bad but I’m still exploring ways to improve the performance. One optimization I tried is to, instead of returning an explicit list of strings as mentioned in the search implementation, return them encoded in a trie, since we can save some operations due to shared prefixes. I have that version on github, but unfortunately that takes 240 seconds to run and requires more memory.

Another way is to parallelize the code. The search for subsequences is independent for each word, so it’s an embarrassingly parallel case. I haven’t tried this path yet.

The constructed trie has 8e5 nodes or ~40% of the size of sum of characters.

Subsequences of “thorough”

The question that inspired this analysis was finding all the subsequences of thorough. It turns out it has 44 subsequences, but most of them are boring, that is, single letter or small words that look completely unrelated to the original word. The most interesting ones are those that start with t and have at least three letters. I selected some of them here:

- tho

- thoo

- thoro

- thorough

- thou

- though

- thro

- throu

- through

- thug

- tog

- tou

- toug

- tough

- trough

- trug

- tug The word with most subsequences is pseudolamellibranchiate, 1088! The word cloud at the beginning of the post contains the 100 words with the largest number of subsequences. I tried to find interesting words among these, but they’re basically the largest words - large words have exponentially more combination of subsequences, and hence the chance of them existing in the dictionary is greater. I tried to come up with penalization for the score:

1) Divide the number of subsequences by the word’s length. This is not enough, the largest words still show on top. 2) Apply log2 to the number of subsequences and divide by the word’s length. In theory this should account for the exponential number of subsequences of a word. This turns out to be too much of a penalization and the smallest word fare too well in this scenario.

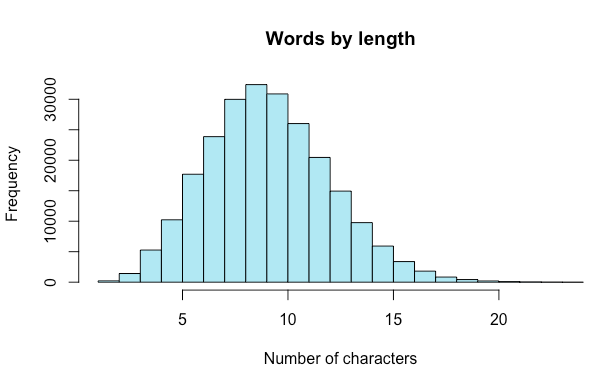

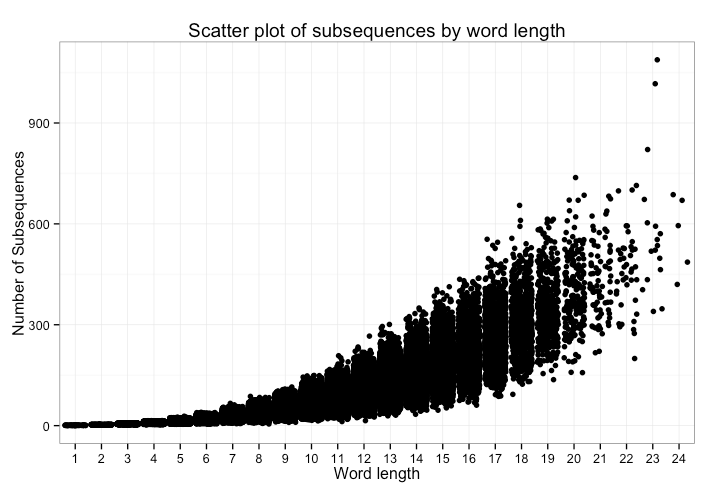

I plotted the distribution of number of subsequences by word lengths. We can see a polynomial curve but with increased variance:

In the chart above, we’d see all points with the same x-value in a single vertical line. One neat visualization trick is to add noise (jitter) so we also get a sense of density.

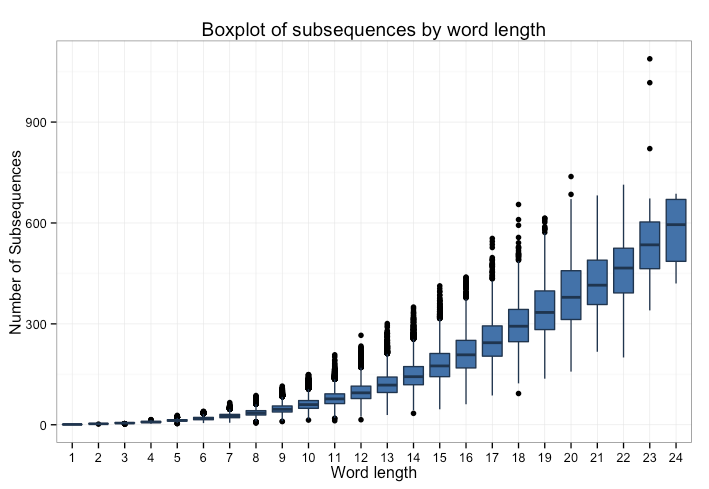

If we use a box plot instead, we can see a quadratic pattern more clearly by looking at the median for each length.

Given this result, I tried a final scoring penalization, by dividing the number of subsequences by the square of the length of the word, but it’s still not enough to surface too many interesting words. Among the top 25, streamlined is the most common word, and it has 208 subsequences.

One interesting fact is that the lowest scoring words are those with repeated patterns, for example: kivikivi, Mississippi, kinnikinnick, curucucu and deedeed. This is basically because we only count unique subsequences.

Conclusion

This was a fun problem to think about and even though it didn’t have very interesting findings, I learned more about OCaml and R. After having to deal with bugs, compilation and execution errors, I like OCaml more than before and I like R less than before.

R has too many ways of doing the same thing and the API is too lenient. That works well for the 80% of the cases which it supports, but finding what went wrong in the other 20% is a pain. OCaml on the other hand is very strict. It doesn’t even let you add an int and a float without an explicit conversion.

I learned an interesting syntax that allows to re-use the qualifier/namespace between several operations when chaining them, for example:

Trie.(empty |> insertString "abc" |> insertString "abd")I also used the library Batteries for the first time. It has a nice extension for the rather sparse String module. It allows us to simply do open Batteries but that overrides a lot of the standard modules and that can be very confusing. I was scratching my head for a long time to figure out why the compiler couldn’t find the union() function in the Map module, even though I seemed to have the right version, until I realized it was being overridden by Batteries. From now on, I’ll only use the specific modules, such as BatString, so it’s easy to tell which method is coming from which module.

References

OCaml