kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > [Paper] Spanner: Google's Globally-Distributed Database

[Paper] Spanner: Google's Globally-Distributed Database

27 Apr 2017

This is the first post under the category “Paper Reading” which will consist in summarizing my notes after reading a paper.

In this post we’ll discuss Spanner: Google’s Globally-Distributed Database. We’ll provide a brief overview of the paper’s contents and study in more details the architecture of the system and the implementation details. At the end, we provide an Appendix to cover some distributed systems and databases concepts mentioned throughout the paper.

Paper’s Overview

Spanner is a distributed database used at Google. It provides a SQL API and several features such as reading data from a past timestamp, lock-free read-only transactions and atomic schema changes.

In Section 2, Implementation, it describes how the data is distributed in machines called spanservers, which themselves contain data structures called tablets, which are stored as B-tree-like files in a distributed file system called Colossus. It describes the data model, which allows hierarchy of tables, where the parent table’s rows are interleaved with the children tables’.

The paper puts emphasis on the TrueTime API as the linchpin that address many challenges in real-world distributed systems, especially around latency. This is described in Section 3.

Section 4 describes technical details on how to implement the distributed transactions and safe schema changes.

In Section 5, the authors provide benchmarks and use cases, in particular F1, a database built on top of Spanner and used by Google’s AdWords team, to address some scaling limitations of a sharded MySQL database.

Architecture

Spanservers

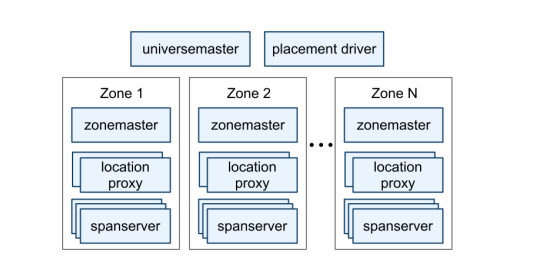

As we can see in Figure 1, Spanner is organized in a set of zones, which are the unit of administrative deployment. Even though there might be more than one zone per data center, each zone correspond to a physically disjoint set of servers (cluster). Within a zone, we have the zonemaster, which the paper doesn’t delve into, the location proxy, which serves as a index that directs requests to the appropriate spanserver, and the spanserver itself, which is the main unit in the system, containing the actual data.

A spanserver contains multiple tablets, which are a map

(key, timestamp) -> value

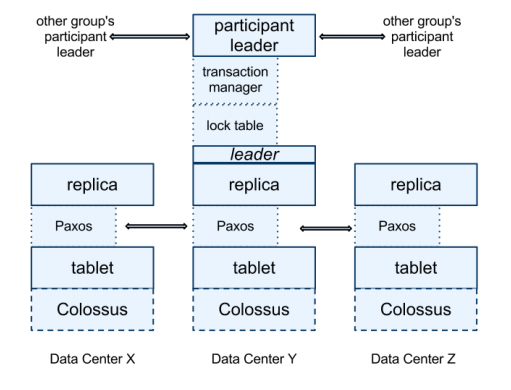

They are stored in Colossus, a distributed file system (successor of Google File System). A spanserver contains multiple replicas of the same data and the set of replicas form a Paxos group, which we can see in Figure 2. Reads can go directly to any replica that is sufficiently up-to-date. Writes must go through a leader, which is chosen via Paxos. The lock table depicted on top of the leader replica in Figure 2 allows concurrency control. The transaction manager is used to coordinate distributed transactions (that is, across multiple groups) and it also chooses the participant leader. If the transaction involves more than one Paxos group, a coordinator leader must be elected among the participant leaders of each group.

Within a tablet, keys are organized in directories, which is a set of contiguous keys sharing a common prefix. A directory is the unit of data, meaning that data movement happens by directories, not individual keys or rows. Directories can be moved between Paxos groups.

Data Model

The paper mentions that its data is in a semi-relational table. This is because it has characteristics from both relational tables (e.g. MySQL tables) and non-relational table (e.g. HBase tables). It looks like a relational table because it has rows, columns and versioned values. It looks like a key-value store table because rows must have a unique identifier, which acts a key, while the row is the value. The qualifier schematized seems to denote that these tables have well-defined schemas (including column types and primary keys).

In particular, the schema supports Protocol Buffers. This means that besides the native types existing in databases (string, int, etc.), the schema supports the strongly typed structures from Protocol Buffers.

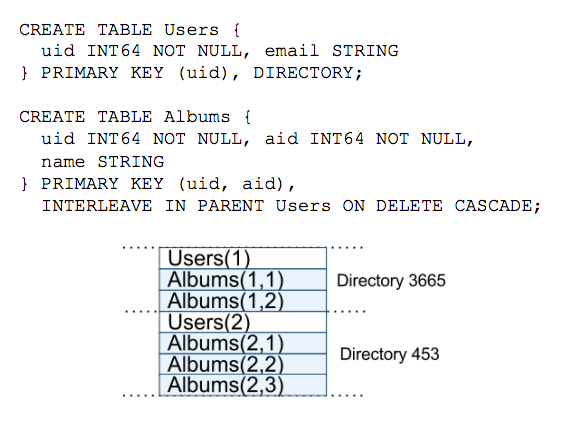

Another feature of this database is how it allows storing related tables with their rows interleaved. This helps having data that is often queried together to be located physically close (co-located). In the example of Figure 3, it stores the Users and Albums interleaved. If we think of this as an use case for the Google Photos application, it should be a pretty common operation to fetch all albums of a given user.

TrueTime API

The main method from the true time API (TT) is:

TT.now(): [earliest, latest]

It returns the current universal time within a confidence interval. In other words, there’s a very strong guarantee that the actual time lies within the returned time range. Let \(\epsilon\) be half of a given confidence interval length and \(\bar\epsilon\) the average across all \(\epsilon\)’s. According to their experiments, \(\bar\epsilon\) varied from 1 to 7ms during the pollings.

Of course, the strength doesn’t lie on the API itself, but the small confidence interval it can guarantee. They achieve this through a combination of atomic clocks and GPSs, each of which have different uncorrelated synchronization and failure sources, which means that even if one of them fails, the other is likely working properly.

Implementation Details

Spanner has three main types of operations: read-write transaction, read-only transaction and snapshot read at a timestamp.

Read-write transactions

The writes in a read-write transaction, or RW for short, are buffered in the client until commit, which means the reads in that transaction do not see the effects of the writes.

First, the client perform the reads, by issuing read requests to each of the leader of the (Paxos) groups that have the data. The leader acquires read locks and reads the most recent data.

Then the client starts the 2 phase commit for the writes. It chooses a coordinator group (a representative among the Paxos groups) and notify the leaders of the other groups with the identity of the coordinator plus the write requests. A non-coordinator group’s leader first acquires write locks and then chooses a prepare timestamp that is greater than all the timestamps issued by this group, to preserve monotonicity, and sends this timestamp to the coordinator’s leader.

The coordinator’s leader acquires write locks and receives all the timestamps from the other leaders and chooses a timestamp s that is greater than all of these, greater than the TT.now().latest at the time it received the commit request and greater than any timestamps issued within the coordinator group.

The coordinator’s leader might need to wait until it’s sure s is in the past, that is, until TT.now().earliest > s. After that, the coordinator sends s to all other leaders which commit their transactions with timestamp s and release their write locks.

This choice of timestamp can be shown to guarantee the external consistency property, that is, if the start of a transaction T2 happens after the commit of transaction T1, then the commit timestamp assigned to T2 has to be grater than T1’s.

Read-only transactions

If the read involves a single Paxos group, then it chooses a read timestamp as the timestamp of the latest committed write in the group (note that if there’s a write going on, it would have a lock on it). If the read involves more than one group, Spanner will choose for timestamp TT.now().latest, possibly waiting until it’s sure that timestamp is in the past.

Conclusion

In this post we learned about some of the most recent Google’s databases, the main pioneer in large-scale distributed systems. It addresses some limitations with other solutions developed in the past: Big Table, which lacks schema and strong consistency; Megastore, which has poor write performance; and a sharded MySQL, which required the application to know about the sharding schema and resharding being a risky and lengthy process.

One thing I missed from this paper is whether Spanner can perform more advanced relational database operations such as aggregations, subqueries or joins. Usually performing these in a distributed system requires some extra component to store the intermediate values, which was not mentioned in the paper.

Appendix: Terminology and concepts

I was unfamiliar with several of the terminology and concepts used throughout the paper, so I had to do some extra research. Here I attempt to explain some of these topics by quoting snippets from the paper.

Spanner is a database that shards data across many set of Paxos. Sharding is basically distributing the data into multiple machines. It’s used commonly in a database context meaning partitioning the table’s rows into multiple machines.

Paxos is a protocol used to solve the consensus problem, in which a set of machines (participants) in a distributed environment must agree on a value (consensus). We discussed it in a previous post, and it guarantees that at least a quorum (subset of more than half of the participants) agree on a value. In “set of Paxos”, it seems that Paxos is an allegory to represent a set of machines using the Paxos protocol.

Spanner has two features that are difficult to implement in a distributed database: it provides externally consistent reads and writes, and globally-consistent reads across the database at a timestamp.

In the context of transactions in a concurrent environment, we need to have a total order of the transactions. This is to avoid problems such as the concurrent balance updates [2]: Imagine we have a bank account with balance B and two concurrent transactions: Transaction 1 (T1) reads the current balance and adds $1. Transaction 2 (T2) reads the current balance and subtracts $1. After T1 and T2 are executed (no matter in which order), one would expect that the final balance remains B. However, if the read from T2 happens before the write from T1 and the write from T2 after, T1 will be overridden and the final balance would be B-$1. The total ordering guarantees that T1 and T2 are disjoint (in time).

To obtain external consistency, the following property must hold: T1’s start time is less than T2’s, then T1 comes before T2 in the total order.

Google has datacenters all over the world. By providing globally-consistent reads at a timestamp, it guarantees that, given a timestamp, it will return the same data no matter which datacenter you ask the data from.

Running two-phase commit over Paxos mitigates the availability problems.

Two-phase commit or 2PC is a protocol to guarantee consistency of distributed transactions. It guarantees that either all transactions will succeed or none will be performed (they’ll rollback). The protocol requires the election of a coordinator among the participant transactions and such election can be performed using the Paxos protocol, which seems to be the case here. In the first phase, the leader must obtain an agreement from all participants and after that it starts the second phase and sends a message to each participant informing them to proceed with the transaction.

To support replication, each spanserver implements a single Paxos state machine on top of each tablet

A Paxos state machine is a method for implementing fault-tolerance [4]. This seem complicated enough to warrant an entire post on this topic, but the basic idea seems to use replicas, each of which containing a copy of a state machine and use this information to guarantee correctness and availability under failures.

Reads within read-write transactions use woundwait to avoid deadlocks

Wound-wait lock. See [6].

A converse approach is the wait-die mechanism. The comparison of these methods is explained here. I haven’t researched enough to understand what the tradeoffs between these two approaches are and why Spanner decided on the first.

References

- [1] Spanner: Google’s Globally-Distributed Database

- [2] Principles of Computer Systems - Distributed Transactions

- [3] Radar - Google’s Spanner is all about time

- [4] Implementing Fault-Tolerant Services Using the State Machine Approach: A Tutorial

- [5] System level concurrency control for distributed database systems

- [6] Distributed Systems Cheat Sheet