kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Tree Ring Matching using the KMP Algorithm

Tree Ring Matching using the KMP Algorithm

13 Mar 2016

Disclaimer: trees and rings are concepts found in Mathematics and Computer Science, but in this post they refer to the biology concepts ;)

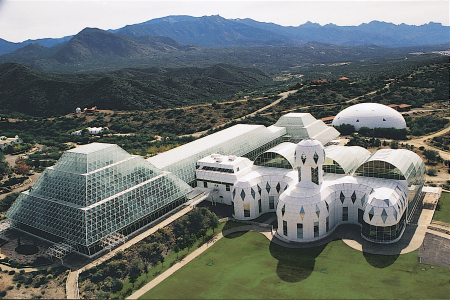

Biosphere 2

Earlier this year I went to Arizona and visited the Biosphere 2. Its initial goal was to simulate a close environment where a group of 6 humans should survive for 2 years without any exchange with the exterior (except sunlight, of course). They had different biomes, including a rain forest, an ocean to a desert.

The plan didn’t go well because they had missed interaction of the plants in one of the seasons, which causes the level of oxygen to fall under the accepted level, so they had to get extern supply. The mission did last 2 years, but was not a perfect closed environment.

Later, another mission was attempted, but had to be abandoned after a few months. The project lost its funding and no more attempts were performed. Nowadays, the place is used by biologists to study environments under controlled conditions and also open to the public for tours (the Nautilus magazine recently wrote more about this).

The tour includes a small museum explaining some of the research, one of them is analyzing trees to understand the ecosystem from the past. According to one of the exhibits, tree rings can be used to determine the age of the tree and also some climate from that period, a process called dendrochronology. The more rings a tree has, the old it is and the width of the tree varies with the climate during the period of its growth.

A lot of the trees alive today are not too old. On the other hand they have fossil of older trees. Since they possibly co-existed for a period of time, it’s possible to combine the data from the rings of both trees by matching the outer rings of the fossil tree with the inner rings of the recent tree.

The Longest Prefix-Suffix String Overlap problem

I thought about the tree ring matching for a while and realized this can be reduced to the problem of finding the longest overlap between the suffix and prefix of two strings. More formally, given strings A and B, find the longest suffix of A that is also a prefix of B.

This problem can be easily solved using a simple quadratic algorithm, which is is probably fast enough for real world instances, possibly in the order of thousands of rings. In Python, we can use the array access to do:

def longest_suffix_prefix_naive(suffix, prefix):

minlen = min(len(prefix), len(suffix))

max_match = 0

for match_len in range(1, minlen + 1):

if prefix[:match_len] == suffix[-match_len:]:

max_match = match_len

return max_matchIn the code above, A is named suffix and B prefix.

But can we do better? This problem resembles a string search problem, where we are given a text T and a query string Q and want to find whether Q appears in T as substring. One famous algorithm to solve this problem is the KMP, named after their authors Knuth Morris and Pratt (Morris came up with the algorithm independently from Knuth and Pratt) which is linear on the size of T and Q.

We’ll see how to use the ideas behind the KMP to solve our problem. So let’s start by reviewing the KMP algorithm.

The KMP Algorithm: A refresher

The most straightforward way to search for a query Q in a text is for every character in T, check if Q occurs in that position:

def substr(Q, T):

tlen = len(T)

qlen = len(Q)

for i, _ in enumerate(T):

match = 0

# Searches for Q starting from position i in T

while match < qlen and \

i + match < tlen and \

Q[match] == T[i + match]:

match += 1

if match == qlen:

print 'found substring in position', iAvoiding redundant searches

Imagine that our query string had no repeated characters. How could we improve the search?

Q = abcde

T = abcdfabcde

^ mismatch in position 4If we were using our naive idea, after failing to find Q in position 4, we’d need to start the search over from T(1) = 'b'. But since all characters are different in Q, we know that there’s no 'a' between positions 1 and 3 because they matched the rest of strings of Q, so we can safely ignore positions 1 to 3 and continue from position 4.

The only case we would need to look back would be if 'a' appeared between 1 and 3, which would also mean 'a' appeared more than once in Q. For example, we could have

Q = ababac

T = ababadac...

^ mismatch in position 5When there is a mismatch in position 5, we need to go back to position 2, because 'abababac' could potentially be there. Let MM be the current mismatched string, 'ababad' above and M the string we had right before the mismatch, i.e., MM without the last letter, in our case, 'ababa'. Note that M is necessarily a prefix of Q (because MM is the first mismatch).

The string M = 'ababa', has a potential of containing Q because it has a longest proper suffix that is also a prefix of Q, 'aba'. Why is it important to be a proper prefix? We saw that M is a prefix of Q, hence the longest suffix of M that is a prefix of Q would be M itself. We are already searched for M and know it will be a mismatch, so we’re interested in something besides it.

Let’s define LSP(A, B) as being the length of the longest proper suffix of A that is a prefix of B. For example, LSP(M, Q) = len('aba') = 3. If we find a mismatch MM, we know we need to go back LSP(M, Q) positions in M to restart the search, but we also know that the first LSP(M, Q) positions will be a match in Q, so we can skip the first LSP(M, Q) letters from Q. In our previous example we have:

Q = ababac

T = ababadac...

^ continue search from here

(not from position 2)We’ll have another mismatch but now MM = 'abad' and LSP(M, Q) = len('a') = 1. Using the same logic the next step will be:

Q = ababac

T = ababadac...

^ continue search from here

(not from position 2)Now MM = 'ad' and LSP(M, Q) = 0. Now we shouldn’t go back any positions, but also won’t skip any characters from Q:

Q = ababac

T = ababadac...

^ continue search from hereIf we know LSP(M, Q) it’s easy to know how many characters to skip. We can simplify LSP(M, Q) by noting that M is a prefix of Q and can be unambiguously represented by its length, that is M = prefix(Q, len(M)). Let lsp(i) = LSP(prefix(Q, i), Q). Then LSP(M, Q) = lsp(len(M)). Since lsp() only depends on Q, so we can pre-compute lsp(i) for all i = 0 to len(Q) - 1.

Suppose we have lsp ready. The KMP algorithm would be:

def kmp(Q, T):

lsp = precompute_lsp(Q)

i = 0

j = 0

qlen = len(Q)

tlen = len(T)

while i < tlen and j < qlen:

if j 0:

j = lsp[j - 1]

else:

i += 1

# string was found

if j == qlen:

print i - jWe have to handle 3 cases inside the loop:

1: A match, in which case we keep searching both in T, Q.

2: A mismatch, but there’s a chance Q could appear inside the mismatched part, so we move Q the necessary amount, but leave T.

3: A mismatch, but there’s no chance Q could appear in the mismatched part, in which case we can advance T.

This algorithm is simple but it’s not easy to see it’s linear. The argument behind it is very clever. First, observe that lsp[j] < j, because we only account for proper suffixes. It’s clear that i is bounded by len(T), but it might not increase in all iterations of the while loop. The key observation is that (i - j) is also bounded by len(T). Now in the first condition, i increases while (i - j) remains constant. In the second, i might remain constant but j decreases and hence (i - j) increases. So every iteration either i or (i - j) increases, so at most 2T iterations can occur.

The pre-computed lsp

How can we pre-compute the lsp array? One simple idea is to, for every suffix of Q, find the maximum prefix it forms with Q. In the following code, i denotes the start of the suffix and j the start of the prefix.

def precompute_lsp_naive(Q):

qlen = len(Q)

lsp = [0]*qlen

i = 1

while i < qlen :

j = 0

while (i + j < qlen and Q[j] == Q[i + j]):

lsp[i + j] = max(lsp[i + j], j + 1)

j += 1

i += 1

return lspThe problem is that this code is O(len(Q)^2). In practice len(Q) should be much less than len(T), but we can do in O(len(Q)), using a similar idea from the main idea of the KMP, but this time trying to find Q in itself.

The main difference now is that we’ll compute lsp on the fly. While searching for Q in Q, when we have a matching prefix, we update the lsp. When we have a mismatch, instead of re-setting the search to the beginning of Q we skip some characters given by the lsp. This works because j < i and we had lsp(k) for k <= i defined. In the following code, the only changes we performed were adding the lsp attribution and having T = Q.

def precompute_lsp(Q):

qlen = len(Q)

lsp = [0]*qlen

i = 1

j = 0

while i 0:

j = lsp[j - 1]

else:

i += 1

return lspWe can use exactly the same arguments from the main code of KMP to prove this routine is O(len(Q)). The total complexity of KMP is O(len(Q) + len(T)).

Solving our problem

At this point we can observe that the problem we were initially trying to solve, that is, find the lsp(A, B), is the core of the KMP algorithm. We can search B, the prefix, in A, the suffix. If we can keep track of the indices i and j, we just need to find when i equals to the length of T, which means there was a (partial) match of B in the suffix of A.

We can generalize our kmp function to accept a callback that yields the indices of the strings at any step:

def kmp_generic(Q, T, yield_indices):

lsp = precompute_lsp(Q)

i = 0

j = 0

qlen = len(Q)

tlen = len(T)

while i < tlen:

if j 0:

j = lsp[j - 1]

else:

i += 1

yield_indices(i, j)Now, if we want an array with the indices of all occurrences of Q in T, we can do:

def kmp_all_matches(Q, T):

matches = []

qlen = len(Q)

def match_accumulator(i, j):

if j == qlen:

matches.append(i - j)

kmp_generic(Q, T, match_accumulator)

return matchesHere we use a nested function as our callback. We can also use kmp_generic to solve our original problem:

def longest_suffix_prefix(suffix, prefix):

slen = len(suffix)

max_match = [None]

def max_matcher(i, j):

if max_match[0] is None and i == slen:

max_match[0] = j

# Search prefix in suffix

kmp(prefix, suffix, max_matcher)

return 0 if max_match[0] is None else max_match[0]Note that the nested function has read-only access to the variables in the scope of the outer function, like max_match and slen. To be able to share data with the nested function, we have to work with references, so we define max_match as a single-element array.

Conclusion

I used to participate in programming competitions. One of the most interesting parts of the problems are their statements. It’s usually an interesting random story from which you have to extract the actual computer science problem. A lot of the times though, the problem writer thinks about a problem and then how to create a story around that problem. It’s nice when we can find real-world problems that can be modelled as classic computer science problems.

I’ve used the KMP several times in the past but never took the time to study it carefully until now, which only happened because I wrote it down as a post.