kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > React.js introduction

React.js introduction

28 Apr 2015

React.js is a open source javascript framework created by Facebook. It abstracts a common pattern in dynamic UI applications and enables some syntax sugars like JSX, embedding XML in Javascript.

In the MVC (Model-View-Controller) pattern, React can be thought as the View. It uses the concept of virtual DOM to avoid unnecessary DOM manipulation (which is expensive) and it uses one-way reactive data flow that can the logic of the application * [1] .

In this post we’ll cover the basics concepts and features of React through a set of small examples.

Setup

React can be easily included with external libraries and is also available as npm packages, but for the sake of simplicity and ease of experimenting with the examples, we’ll be using JSFiddle in this tutorial.

JSFiddle requires some setup to work, especially due to JSX syntax. The easiest way to try the examples yourself is forking the examples we’ll provide here.

The basic example: Hello World

Let’s start with the simplest example: a simple stand alone component that renders the following markup:

<div>Hello World</div>The Javascript code is the following (jsfiddle):

var HelloWorld = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <div>Hello World</div>;

}

});

React.render(<HelloWorld />, document.body);There are a couple of observations we can make here. First off, the JSX syntax. Note how we pass an XML tag to the React.render() function. It’s a syntax sugar JSX provides, and it gets transpiled to a function call, in particular:

React.createElement(HelloWorld);where HelloWorld is the react class we created above. The same is true for the <div> tag in the render() method. In this case though, it’s a base HTML element, so it has a builtin function in React:

React.DOM.div()Finally, all React classes must implement the render() method, which returns other React components, which will eventually get converted to DOM elements and set as children to document.body. If we inspect the HTML source of the generated page we can see the generated tags:

Terminology. We refer to the object passed to React.createClass() as the React class and an instance of this class as the React component. When we talk about objects, we are referring to Javascript native objects.

Parametrizing the component using props

A static component is not very flexible, so to be able to customize the component, we can pass parameters. Let’s suppose that instead of rendering Hello World, we want our component to render Hello plus some custom message. We can use props (short for properties) for this (jsfiddle):

var Hello = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <div>Hello {this.props.text}</div>;

}

});

React.render(<Hello text={"Universe"} />, document.body);In this version, we are passing a property, text, to the Hello instance, and it’s read within the class using this.props.text. More generally, this.props is an object that contains all properties passed to it.

Even though it’s optional, I think it’s a good practice to list the accepted properties a component can take by setting the propTypes property in the react class definition. It expects an object where the keys are the possible properties and the values their types. The possible types are in React.PropTypes, which include the basic javascript one, but also allows for custom types (like other React classes for example) or multiple types (string or number for example) * [2] .

In our case, we expect text to be a string, so we can simply do (jsfiddle):

var Hello = React.createClass({

propTypes: {

text: React.PropTypes.string

},

render: function() {

return <div>Hello {this.props.text}</div>;

}

});

React.render(<Hello text={"Universe"} />, document.body);Besides documenting the component, it will add type-checking for free. In this case, passing something other than a string will raise a warning.

Making the component stateful

We can think of props as arguments to the constructor of a class. Classes are usually stateful, that is, they make use of internal variables to encapsulate logic, to isolate implementation details from the external world.

The same idea can be applied to React components. The internal data can be stored in an object called state.

Let’s create a simple element to display the number of elapsed of seconds since the page was loaded (jsfiddle).

var Counter = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {count: 0};

},

componentDidMount: function() {

setInterval(this.updateCount, 1000);

},

updateCount: function() {

var nextCount = this.state.count + 1;

this.setState({count: nextCount});

},

render: function() {

return <div>Seconds: {this.state.count}</div>;

}

});

React.render(<Counter />, document.body);There are a couple of new concepts to be understood in this example. First, we implemented the getInitialState(), which initializes the object this.state when the component is instantiated. In this case we are initializing one state called count. The render() method reads from that variable.

We also implement the componentDidMount() method. We’ll explain what it does in more detail later, but for now, it’s important to know it’s called only once and after the render() method. Here we are using the setInterval() function to execute the updateCount() method every second. In general, if we are passing a callback that is a “method” (function from an object), we usually want to provide the context, which is normally this, so we would need to call

setInterval(this.updateCount.bind(this), 1000);Instead, since React auto-binds , we can pass the method without binding * [3] .

The update() function will read from this.state and increase it. By calling this.setState(), not only it will set this.state.count with the new value, but will also call render() again. As we mentioned before, the second call of render() doesn’t cause the componentDidMount() to be called.

This pattern of calling render() constantly is pretty common in dynamic GUIs and in React it was modelled in a way that render() is a function of this.props and this.state and we don’t have to worry about keeping track of when to re-render the screen after changing data.

React Children

React components can return other custom components in their render() method and also we can nest React components. One simple example is the following (jsfiddle):

var Item = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <li>{this.props.text}</li>;

}

});

var List = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <ol>{this.props.children}</ol>

}

});

var Container = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return (

<List>

<Item text="apple" />

<Item text="orange" />

<Item text="banana" />

</List>

);

}

});

React.render(<Container />, document.body);Here, Container returns two other React components, Item and List, and Item is nested within List. The list of components nested within another component is available as this.props.children, as we can see in the List.render() method.

Updating. We saw that whenever we change states (by calling setState()), it triggers a re-render. When a component is instantiated from the render() method of another component, calling render() will also trigger updates to it (and recursively, the nested components). To illustrate that, let’s modify the example above with the following (jsfiddle):

...

var List = React.createClass({

render: function() {

if (this.props.ordered) {

return <ol>{this.props.children}</ol>;

} else {

return <ul>{this.props.children}</ul>;

}

}

})

var Container = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {ordered: true};

},

render: function() {

return (

<div>

<List ordered={this.state.ordered}>

<Item text="apple" />

<Item text="orange" />

<Item text="banana" />

</List>

<button onClick={this.toggleOrdered}>

Click Me

</button>

</div>

);

},

toggleOrdered: function() {

this.setState({ordered: !this.state.ordered});

}

});

...There are a couple of new things here. First, we added the native button component and passed a callback to the onClick property. It’s the equivalent to the onclick for DOM elements. Whenever the button is clicked, we toggle the state representing the type of list to render (ordered/unordered).

Whenever the Container.render() method is invoked, the render() method from List and Item is called as well. For the list it makes sense, because its render function depends on props.ordered that is being changed. None of the Items are changing thought, but it gets re-render nevertheless. That’s the default behavior from React. In the “Cached rendering” section, we’ll see how to customize this.

Again, note that a component is only updated if it’s instantiated starting from a render() method. For example, both List and Item are created when Container.render() is invoked. On the other hand, even though Item is used within List (through this.props.children) it’s not instantiated there, so it doesn’t get updated if List.render() is called (jsfiddle).

Virtual DOM

DOM manipulation is usually the most expensive operation in highly dynamic pages. React addresses this bottleneck by working with the concept of virtual DOM. After the first render() gets called, React will convert the virtual DOM to an actual DOM structure after which the component is considered mounted (and componentDidMount() is called).

Subsequent calls of render() changes the virtual DOM, but React uses heuristics to find one what changed between two virtual DOMs and only update the difference. In general only a few parts of the DOM structure is changed, so in this sense React optimizes the rendering process and let us simplify the code logic by re-rendering everything all the time.

This process of updating only part of the DOM structure is called reconciliation. You can read more about it in the docs * [4] .

We need to be careful with conditional rendering, since it can defeat the purpose of the virtual DOM. We used conditional rendering in the React Children section, in the List.render() function. Let’s create a similar example, to make the problem clearer (jsfiddle):

var Text1 = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <p>Hello</p>;

}

});

var Text2 = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <p>World</p>;

}

});

var Container = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {count: 0};

},

componentDidMount: function() {

setInterval(this.updateCount, 1000);

},

updateCount: function() {

var nextCount = this.state.count + 1;

this.setState({count: nextCount});

},

render: function() {

var content = null;

if (this.state.count % 2 == 0) {

content = <Text1 />;

} else {

content = <Text2 />;

}

return content;

}

});

React.render(<Container />, document.body);Here we introduced two dummy new React classes, Text1 and Text2, which render “Hello” and “World” respectively. The render() function of Container returns one of the other alternated.

If we run this example, we can verify Text1 and Text2 get mounted every time Container.render() is called. The reason is that whenever React runs the diff heuristic, the previous tree is completely different from the other.

One solution is to always render both components, but hide one of them using CSS. A proposed solution for the example above is here.

Cached rendering

As we saw in the React Children section, we may trigger render() of a component even when nothing has changed at all. In 99% of the cases, it’s probably fine, because React will be smart enough to prevent DOM manipulations, which is the expensive part anyway.

In case the render() call is expensive, we can control when it gets called by implementing the shouldComponentUpdate() method. By default, it always returns true, but it receives the next set of props and state, which we can inspect to determine whether anything has changed.

Comparing complex objects can be tricky if we don’t know the structures very well. Also caching in general introduces complexity. For example, whenever we do any changes to our code, we need to make sure to update the shouldComponentUpdate() logic, otherwise the render() function might not be called when it should.

Another issue is that props and state can be mutated without the parent component changing them or without calls to setState(). This can cause unexpected problems. Consider the following example (jsfiddle):

var Container = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {data: {key: "value"}};

},

shouldComponentUpdate: function(nextProps, nextState) {

return this.state.data.key != nextState.data.key;

},

render: function() {

return (

<div>

{this.state.data.key}

<button onClick={this.updateState}>Update</button>

</div>

);

},

updateState: function() {

// Modifying state is anti-pattern. We should clone it!

this.state.data.key = "new value";

this.setState({data: this.state.data});

}

});Here we only have one state, data, an object with a single key. This is a simple enough object to cache, right? But in the example, if you click “Update”, even though we did mutate the state and called setState(), it doesn’t do anything. The reason is that in shouldComponentUpdate(), nextState.data and this.state.data are references to the same object.

One idea is using immutable data structures as state and props. For example, Om is a ClojureScript interface to React and it works with immutable data * [5] .

Mixing with non-React code

React can be incrementally adopted in any existing Javascript codebase. Inserting Javascript under a DOM element is straightforward, since that’s what React.render() does.

Inserting an existing DOM subtree under a React component requires more work. As we saw, React works with the concept of virtual DOM, but we have access to the actual DOM after the component mounted. In particular, we can do it at the componentDidMount() method. In the example below, we create a toy text DOM node, and insert into the generated div DOM element (jsfiddle).

var Hello = React.createClass({

componentDidMount: function() {

var root = this.getDOMNode();

var text = document.createTextNode(" world");

root.appendChild(text);

},

render: function() {

return <div>hello</div>;

}

});

React.render(<Hello />, document.body);Here we are artificially creating a fake text node, but we could potentially insert an entire subtree under the div element. React enables referring to components by ids. In this case, we just need to add the ref property with an unique identifier. Later, when the component is mounted, the corresponding DOM element reference will be available at the this.refs object. More in refs * [6] .

One way communication

Some frameworks are created to implement patterns. There’s a natural tradeoff between how much boilerplate it saves someone vs. how much it limits it. React is relatively low-level, and thus it still offers a lot of flexibility. One constraint that is imposes it’s the one-way communication between components, that is, during render, we can only pass information from the parent to the children. It’s possible to pass information from children to parents via callbacks, but that usually triggers re-renders.

I struggled in this paradigm right in the beginning, but in the long run, this constraint makes the code much simpler, especially when we have many components interacting with each other, and tracking down what is affecting what is a pain. With the one-way communication, we tend to concentrate logic in fewer places, and if we think in terms of graph theory, each component bring a node, React forces us to have a tree, whereas in an unconstrained environment, we can have arbitrary graph structures.

To make it clearer, let’s try a very simple example. We want a component with a selector and a list, but depending which value of the selector, the list displays a different set of items (jsfiddle).

var List = React.createClass({

render: function() {

var items = {

color: ['Red', 'Green', 'Blue'],

fruit: ['Apple', 'Banana', 'Orange']

};

var reactItems = items[this.props.type].map(function(item) {

return <li>{item}</li>;

}, this);

return (

<ul>{reactItems}</ul>

);

}

});

var Selector = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return (

<select onChange={this.handleSelection} value={this.props.selected}>

<option value="color">Color</option>

<option value="fruit">Fruit</option>

</select>

);

},

handleSelection: function(e) {

this.props.onChange(e);

}

});

var Container = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {

selected: 'fruit'

}

},

render: function() {

return (

<div>

<Selector

onChange={this.handleSelection}

selected={this.state.selected}

/>

<List type={this.state.selected} />

</div>

);

},

handleSelection: function(e) {

this.setState({selected: e.target.value});

}

});Note how we store the selected value not in Selector, but rather in the parent of Selector (Container), because Selector cannot communicate with List directly. Now, Container is the source of truth and both Selector and List only read from this value.

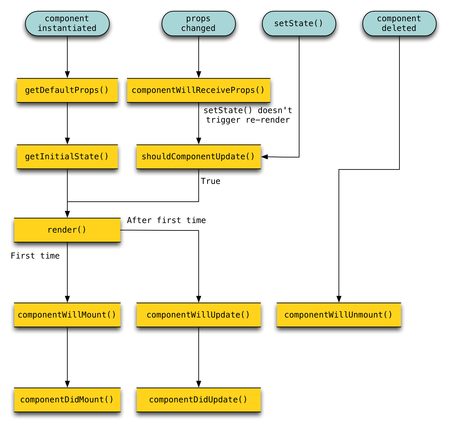

Component Lifecycle

React can be thought as a state machine with many stages. It offers hooks to some these stages, some of which we didn’t cover here, but it’s good to have a picture.

The following chart represents the sequence of function calls (click for a full image). The blue nodes at the top represent external actions and the yellow nodes represent the methods that get called in sequence when that happens:

More http://facebook.github.io/react/docs/component-specs.html

Conclusion

In this post we covered a couple of features from React by small examples.

React.js is a pretty neat framework and is very fun to work with. I’m trying to study more advanced use cases, especially regarding exception handling and performance, so if I find anything interesting, I can write new posts.