kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Haskell Profiling and Optimization

Haskell Profiling and Optimization

08 Oct 2014

I’ve been practicing my Haskell skills by solving programming challenges. During my ACM-ICPC competitor days, I used to practice a lot on SPOJ. The good thing about SPOJ is that it accepts submissions in many many languages (most other sites are limited to C, C++, Pascal and Java).

There’s a Brazilian fork of SPOJ, called SPOJ-Br. I preferred using this one because it contains problems of Brazil’s national high school contests, which are usually easier.

The problem

One of the problem I was just trying to solve boils down to: Given a list of numbers, one in each line from stdin, read the first line as N. Then return the sum of the next N lines. Repeat until N = 0.

This problem is pretty straightforward to do in C++, but for the Haskell version I started getting time limit exceeded (when you program takes more time than the problem setters expected). I had no clue on what was causing this, but I happened to read the Profiling and Optimization chapter from Real World Haskell.

This chapter is particularly well-written and introduces a lot of new concepts and tool, which will be the focus of this post.

The program

The code to solve the aforementioned problem is quite simple: we convert all lines to an array of int’s (using (map read) . lines,), read the first line as n, take the first n entries and recurse for the remaining of the entries:

main = interact $ unlines . f . (map read) . lines

f::[Int] -> [String]

f (n:ls)

| n == 0 = []

| otherwise = [show rr] ++ (f rest)

where (xs, rest) = splitAt n ls

rr = sum xs

f _ = []For this code, I’ve generated a random input of 10 chunks of 100k entries, for a total of 1M lines. Running it with the following command:

time ./test_unline_line arq.out

Resulted in:

` real 0m23.852s user 0m23.699s sys 0m0.147s `

Now, let’s profile to get more details.

Setting up profiling

To generate profiling traces from our program, we need to compile it using some extra flags. Suppose our source code is named program.hs. We can run:

ghc -O2 prog.hs -prof -auto-all -caf-all -fforce-recomp -rtsoptsLike in gcc, ghc has different levels of optimization, and in this case we’re using O2. The -prof tells ghc to turn on profiling.

When profiling our code, we need to specify the cost centers, that is, pieces of code we want to inspect. A way to do that is annotating functions. For example, we could annotate an existing function as follows:

foo xs = {-# SCC "foo" #-} ...

alternatively, we can use the -auto-all flag for adding automatic annotations to all functions, which is also less intrusive (no code modifications).

Haskell memoizes functions with no arguments, so even if we invoke then multiple times in the code, they’re only evaluated once. These functions are called Constant Applicative Forms, or CAF

We can turn on the profiling for CAF’s using the option -caf-all.

-fforce-recomp will force recompilation. ghc might not compile the file again if the source code didn’t change, but if we’re playing with different flags, then we want to force it.

Haskell compiled code is linked to a run time system (RTS) which offers a lot of options. To be able to provide this options in when running a program, we have to use the flag -rtsopts.

Static report

A quick way to gather some statistic from the running program is by passing the -sstderr flag to the RTS, so we can do

time ./prog +RTS -sstderr < arq.in

Which generated:

18,691,649,984 bytes allocated in the heap

1,300,073,768 bytes copied during GC

7,155,200 bytes maximum residency (240 sample(s))

335,312 bytes maximum slop

21 MB total memory in use (0 MB lost due to fragmentation)

Generation 0: 35414 collections, 0 parallel, 0.76s, 0.81s elapsed

Generation 1: 240 collections, 0 parallel, 0.35s, 0.39s elapsed

INIT time 0.00s ( 0.00s elapsed)

MUT time 11.89s ( 11.97s elapsed)

GC time 1.10s ( 1.20s elapsed)

RP time 0.00s ( 0.00s elapsed)

PROF time 0.00s ( 0.00s elapsed)

EXIT time 0.00s ( 0.00s elapsed)

Total time 12.99s ( 13.18s elapsed)

%GC time 8.5% (9.1% elapsed)

Alloc rate 1,572,435,294 bytes per MUT second

Productivity 91.5% of total user, 90.2% of total elapsedWith this report, we can see things like the amount of memory used and the time spent by the garbage collector.

Time and Allocation Profiling Report

If we want a break-down by cost centers, we can run our program with the -p argument. This will generate a prog.prof file:

time ./prog +RTS -p < arq.in

Sat Sep 27 16:25 2014 Time and Allocation Profiling Report (Final)

test_unline_line +RTS -p -RTS

total time = 0.34 secs (17 ticks @ 20 ms)

total alloc = 10,736,138,528 bytes (excludes profiling overheads)

COST CENTRE MODULE %time %alloc

main Main 100.0 98.8

f Main 0.0 1.2

individual inherited

COST CENTRE MODULE no. entries %time %alloc %time %alloc

MAIN MAIN 1 0 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

main Main 242 2 100.0 98.8 100.0 100.0

f Main 243 11 0.0 1.2 0.0 1.2

CAF Text.Read.Lex 204 4 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF GHC.IO.Handle.FD 174 3 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF GHC.IO.Encoding.Iconv 135 2 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF GHC.Conc.Signal 128 1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0From the above, we can see most of the time is being spent on the main function.

Graphic Allocation Profiling Report

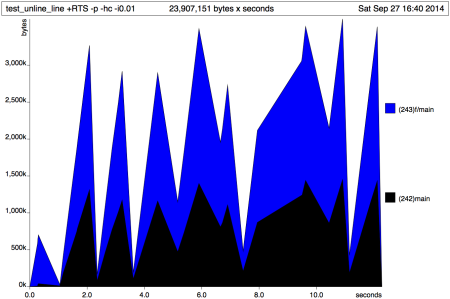

The report above is useful for profiling the overall time and memory allocation in the program. We can also see a time-series of heap allocation. We can break down by different dimensions, one common is by cost-center, which is done simply by adding the -hc flag:

time ./prog +RTS -p -hc < arq.in

This will generate a prog.hp file (heap profile). In our case, the file contained only a few samples (points), which might not give a good picture of the memory behavior. We can provide another parameter -iP, where P is the period of sampling. Doing it with P=0.01,

time ./prog +RTS -p -hc -i0.01 < arq.in

We get much more samples. Now we can use a tool to parse this data into a chart using gnuplot. The output format is post script. In my case, I find it better to use a pdf viewer, so I’ve used another tool, ps2pdf :)

` $ hp2ps -c prog.hp $ ps2pdf prog.ps `

The -c option tells hp2ps to use colors in the charts (it’s grayscale by default). After opening the generated prog.pdf in our favorite pdf reader we get:

The spikes in the chart represent the chunks of lists. Ideally haskell could be completely lazy and stream the lists instead of loading it up into memory.

Optimizing our code: Bang Patterns

One way to avoid loading up the entire list in memory is to write the sum function as an accumulator. In the example below, g' will recursively accumulate the sum of each chunk and append the result with the results of the remaining chunks:

main = interact $ unlines . g . (map read) . lines

g::[Int] -> [String]

g (n:ls)

| n == 0 = []

| otherwise = g' n ls 0

g _ = []

g' n (l:ls) cnt

| n == 0 = [show cnt] ++ (g (l:ls))

| otherwise = g' (n-1) ls (cnt + l)If we run this code this won’t actually improve the memory footprint comparing to the previous attempt. The reason it that at each recursion call, because we’re doing it lazily, we keep a reference to the variable cnt until we reach the end of the chunk to compute the sum.

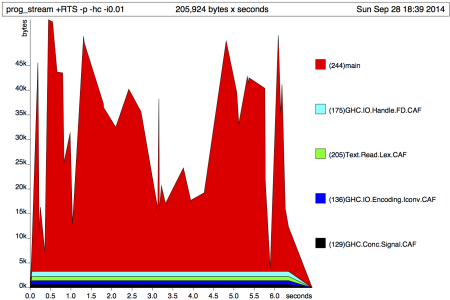

A way to force strictness for cnt is using a language extension, the Bang Patterns. We just need to do two changes in the code above: add the macro at the top of the file and in the g' function definition, use !cnt. This will force cnt to be evaluated strictly (instead of lazily).

{-# LANGUAGE BangPatterns #-}

main = interact $ unlines . g . (map read) . lines

g::[Int] -> [String]

g (n:ls)

| n == 0 = []

| otherwise = g' n ls 0

g _ = []

g' n (l:ls) !cnt

| n == 0 = [show cnt] ++ (g (l:ls))

| otherwise = g' (n-1) ls (cnt + l)The resulting heap graph shows the benefits of doing this:

Note that now the maximum memory usage is 45K, 2 orders of magnitude less than the 3M of our initial version. Even though changing the code we managed to use less memory, it didn’t improve the runtime significantly (both were around 4 secs). It’s time to investigate other tools and strategies.

The core

Another idea to improve the performance of a program is to get the optimized code that is generated by the ghc compiler before transforming it into imperative machine code, which is know as the core. It’s still a valid Haskell syntax, but it’s very hard to read. In [1], the authors suggest investigating the core to identify where the compiler is not optimizing properly and then modify the original code to help it.

We can generate the core code by compiling with the following instructions:

$ ghc -O2 -ddump-simpl prog.hs

The problem is that this generates a inlined code, which makes it hard to understand what’s going on. I couldn’t get any good idea from the core from prog.hs, but we can take a learn a bit how to better interpret it. There are some interesting constructions here:

Function annotations. Every function generated has annotations, which make it harder to read:

Main.f [...]

[GblId, Arity=1, Caf=NoCafRefs, Str=DmdType S]According to [2], those are used by ghc for later stages of compilation. For inspecting the code though, we could remove the annotations.

Primitive types and boxed types. Most Haskell types are high-level abstractions that only point to data in the heap, but to not contain the actual values. For one side, it leads to cleaner programs and simpler APIs, but on the other hand it adds an overhead. When optimizing code, the compiler will try to convert types to the primitive versions (unboxing), so it’s rare that we’ll need to work with primitive types directly.

By convention primitive types are ended on the # sign. For example, comparing to C primitive types in parenthesis, we have Int# (long int), Double# (double), Addr# (void *).

We also see the GHC.Prim.State# type. GHC.Prim contains a collection of unboxed types. In particular, the State monad has a primitive type and it appears in the generated code because the IO monad (used in the function main through interact) can be written in terms of the State monad [2].

Gonzalez studies the core in more depth in this blog post, especially in regards to the IO monad. It’s an interesting read.

Strings vs. Bytestrings

Still stuck in the running time problem, I decided to ask a question on Stack Overflow and even though the main question was not answered, someone suggested using ByteStrings instead of Strings.

Chapter 8 of Real World Haskell actually talks about ByteStrings as a cheaper alternative to Strings [1]. The reason is that Strings are essentially a List of ` Chars, so we have 2 layers of abstraction, while ByteString` is a data structure specialized for strings.

One limitation of ByteStrings is that it only works with 8-bit characters. For Unicode handling, the most common alternative is Data.Text, which also has a low overhead compared to String and can handle Unicode [3].

Converting the code was basically changing the Prelude function calls dealing with Strings to use the ByteStrings. Since most of the functions have the same name, we had to qualify them.

import qualified Data.ByteString as B

import qualified Data.ByteString.Char8 as BC

main = BC.interact $ BC.unlines . f . (map (getInt . BC.readInt)) . BC.lines

getInt::Maybe (Int, BC.ByteString) -> Int

getInt (Just (x, _)) = x

getInt Nothing = 0

f::[Int] -> [B.ByteString]

f (n:ls)

| n == 0 = []

| otherwise = [(BC.pack . show) rr] ++ (f rest)

where (xs, rest) = splitAt n ls

rr = sum xs

f _ = []Running this code yields a running time of 0.4s, roughly 10x faster than the String version. This was enough to make this program pass in the online judge.

Conclusion

This post was motivated by a slow running program when solving a programming challenge. While looking for ways to improve it, we learned some techniques for profiling code. We also learned about the core, which is a optimized (and hard to read) Haskell code generated by ghc during the compilation.

It turned out it the improvement necessary to speed up the code was only swapping String with ByteString. Henceforth, I’ll make sure to always use ByteStrings, at least when writing programming challenges solutions.

Upon writing this post, I stumbled into Zyang’s posts, which seem to delve into great detail on the core functionality. I didn’t have time to read, but I’ve bookmark those for future reading: Unraveling the mystery of the IO monad and Tracing the compilation of Hello Factorial!.