kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Emacs Lisp Introduction

Emacs Lisp Introduction

01 Mar 2014

Richard Stallman is an american programmer and software freedom activist. He graduated from Harvard magna cum laude in Physics and started his PhD in Physics at MIT, but after about one year, he decided to focus on programming at the MIT AI Laboratory. There, he developed several softwares, including Emacs, which we’ll talk about in this post.

Emacs is named after Editor MACroS, since it was originally a macro editor for another editor, called TECO.

I’ve been using emacs since 2005, but never took the time to learn about elisp, which is the emacs dialect of Lisp and which emacs uses to implement a lot of its functions and the way it allows users to extend it.

In this post we’ll cover the basics of the elisp language. Most of if was based in the “Introduction to Programming in Emacs Lisp” by Robert Chassell and the Emacs Lisp Manual.

Setting up the environment

In the following sessions we’ll have a lot of examples, so let’s setup an environment to run them.

Interpreter. For an interactive way to test the code snippets, we can use the elisp interpreter, integrated with emacs, called ielm. To open it, just run M-x ielm.

Running from a text file. An alternative to using the interpreter is by evaluating the code in a given region. To do that, select a region and run eval-last-sexp (C-x C-e).

Now, let’s cover some of the basic aspects of emacs lisp.

Basics

List Centered. Lisp stands for list processing and as this suggests, it is highly centered on lists. Usually we use lists to perform the evaluation of some expression (which is also referred to form). One common expression is a function call. In this case, the first element of the list is the function and the other elements are parameters to the function. For example, we can call the function max:

(max 3 4) ;; returns 4Similarly, for operators, we first provide the operator and then the parameters. For example, to add two numbers:

(+ 2 3)We can see then that for arithmetic expressions we use the prefix (polish) notation, instead of the infix notation as in languages such as C++, Python and Haskell.

To use a elisp list to represent an actual list, we use the single quote.

'(1 2 3)Printing. For simple cases, printing can be handy. On elisp we can use the function message. Run the following in the interpreter or run eval-last-sexp with that text selected:

(message "hello world")This will print out the hello world string in the messages buffer, which can be viewed by running switch-to-buffer command (M-x b) and going to the *Messages* buffer.

Comments. In elisp, comments are inline and start after a semi-colon (unless it’s part of a string): ;.

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;; This is a way to emphasize a comment

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

(message "hello; world") ; simple inline comment

; will print hello; worldVariables

As in other languages, elisp has variables. But in elisp, variable names can contain symbols that wouldn’t be allowed as in some more common languages like +,-,*.

That is possible because in elisp we don’t have in-fix notation, so a variable named a+b is not ambiguously mistaken by a plus b, which has to be defined as (+ a b)

To set a variable you can use the set function:

(set 'x '(1 2))We quote both elements because we want their literal and not to evaluate them. In most of the cases, we want the left hand side of the assignment to be a literal (representing the variable), so we use the shortcut setq:

(setq x '(1 2)) ;; Equivalent to (set 'x '(1 2))Another option is to use defvar. The difference between defvar and setq is that defvar won’t set the variable again if it was already defined.

(setq x '(1 2))

(defvar x '(3 4)) ;; x still holds (1 2)When we use set/setq/defvar, we create a variable in the global scope. To restrict variables to a local scope, we can use the let.

(let (a (b 5))

(setq a 3)

(+ a b)

) ;; returns 8For this function, the first argument is a list of the variables which will be in the local scope. You can initialize a variable with a value by providing a pair (variable value) like we did with b above.

To indicate that a variable should not be changed, we can use the defconst macro. Note that it doesn’t actually prevent from overriding with setq though.

Another form of setting variable is using the special form defcustom. The first three parameters are the same of defvar. In addition, we can provide a documentation string as the fourth parameter and following are any number of arguments in the form

<keyword>:<value>

Common examples of keywords are type, option and group.

The type can have a different set of values such as string, integer, function, etc.

A custom group represents a series of custom variables and or other custom groups. Thus, one can organize groups in a tree hierarchy. When specifying the group keyword, we can provide an existing group such as applications, or define our own.

Let’s define our custom group for learning purposes:

(defgroup my-custom-group nil

"This is my first custom group"

:group 'applications

)In the definition above, we’re creating a group called my-custom-group. The second argument is the list of custom variables in the group, which in our case is empty. The third argument is a description of the group and then there’s a list of key-value pairs, as in defcustom. In the example above, we’re making our new group a subgroup of the existing applications group.

Now, let’s create a custom variable in that group:

(defcustom my-custom-var nil

"This is my first custom variable."

:type 'string

:group 'applications)Let’s add these definitions to our init file (e.g. .emacs or .emacs.d/init.el) and re-open emacs.

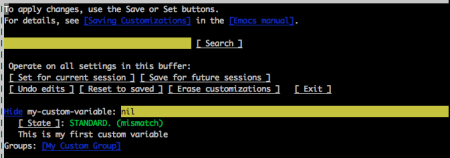

We can browse the custom variables by typing M-x customize to go the *Customize Apropos* buffer. In this buffer, there’s the option to search for variable names or groups. Let’s search for my-custom-variable in the search box:

We can edit its value by changing from nil in the yellow box above. Let’s put an arbitrary string, such as "some-value" and then hit the [Save for future sessions] button.

This should change the init file with something like:

(custom-set-variables

'(my-custom-variable "some-value")

)List Manipulation: cons, car and cdr

One distinct trait of Lisp and Emacs is their alternative naming conventions. For example, what most people refer to copy and paste, emacs uses kill and yank.

Lisp, on its merit, has two important list functions curiously named car and cdr. The function car stands for Contents of the Address part of the Register and cdr for Contents of the Decrement part of the Register.

The car function will retrieve the first element of the list and cdr will get the remaining part of it.

(car '(1 2 3)) ;; 1

(cdr '(1 2 3)) ;; (2 3)Another important function with a more intuitive meaning is cons, a short for constructor. It takes an element and a list, and preprends the element to the list and returns a new list:

(cons 1 (2 3)) ;; (1 2 3)For those familiar with Haskell, cons is like the (:) operator, car is head and cdr is tail.

Conditionals

In elisp we can use the if special form, which can take 2 or 3 arguments.

(if <condition> <then clause> <optional else clause>

The first argument is a predicate. A predicate is anything that after evaluated returns true or false. In elisp, both nil and the empty list are considered false. Anything else is true.

If the condition evaluates to true, the second argument is evaluated and returned. If it’s false and the third argument is provided, it will evaluate it and return. If it’s false and the third argument is not provided, it will just return false (nil).

Let’s do a dummy example. Suppose we have an existing variable x and we want to print a message depending on whether it’s negative:

(if (> x 0)

(message "x is positive")

(message "x is negative")

)Block of code. If besides printing a message we want to do some calculations, we would need to evaluate multiple statements, but the second argument of if takes a single one. To solve this, we can use the progn function, which will combine a list of statements into a single one.

In our example above, if besides printing a message in case the number is negative, we wanted to set x to positive, we could do something like:

(if (> x 0)

(message "x is positive")

(progn

(message "x is negative")

(setq x (* -1 x))

)

)Loops

We can use a loop with the while function. It takes a predicate as the first argument and one ore more arguments which will be executed while the predicate evaluates to true. Another simple example:

;; Print numbers from 0 to 9

(let ((x 0))

(while (< x 10)

(message (number-to-string x))

(setq x (+ x 1))

)

)For the example above, we can alternatively use the dotimes function, which executes a series of statements an specified number of times, much like a for in other languages.

(dotimes (x 10 nil)

(message (number-to-string x))

)It takes two or more parameters. The first is a list of three elements, the first element will represent the counter (which starts at 0), the second is the number of repetitions and the third is executed after the loop is over. The other parameters are evaluated in the loop.

Another handy function is the dolist, which will iterate through a list for us. For example:

(dotimes (elem '("a" "b" "c") nil)

(message elem)

)It takes two or more parameters, the first is a list of three elements: a variable which will contain the an element at each iteration; the list to be iterated on; an expression to be evaluated when finishing the loop. The other parameters are the body of the loop.

Functions

To define a function, we can use the special defun form.

(defun add (a b)

"This simple function adds to numbers"

(+ a b)

)It takes several arguments. The first one is the name of the function, the second is a list representing the parameters of that function, the third, optional, is a string describing what the function does. The remaining arguments are executed and we evaluate a function and the last evaluated argument is returned.

Anonymous functions. W can also create an anonymous (lambda). The example above would be done as:

(setq add (lambda (a b)

(+ a b)

))But this time we need to call this function through funcall. This is because at runtime, add can potentially have any type (not necessarily a function), so we might not know it can be invoked as a function.

(funcall add 3 4)Recursion. We can also define a function in terms of itself to implement recursion. The classical factorial example can be done as:

(defun factorial (n)

"Computes the factorial of n"

(if (<= n 1)

1

(* n (factorial (- n 1)))

)

)Commands. Within emacs, it’s handy to ask for the input parameters from the user. For that we can use the interactive option. Using the example above, we can ask the input for the factorial function:

(defun printFactorial (n)

(interactive "n")

(message (number-to-string (factorial n)))

)To run this, first execute execute-extended-command and then execute printFactorial. After hitting enter, you’ll be prompted to input a number, which will feed the function printFactorial.

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve learned a bit about elisp. In future posts, we’ll cover some of the API emacs provides for extending it.

Robert Chassell mentions that “Introduction to Programming in Emacs Lisp” is a book for non-programmers, but he digs into functions definitions and implementation details that would be uninviting for people learning how to program.