kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Zippers and Comonads in Haskell

Zippers and Comonads in Haskell

01 Oct 2013

In this post we are going to talk about Zippers and Comonads in Haskell. First we’ll present a basic definition of Zippers and show an application for trees. We’ll then talk about Comonads and how Zippers applied to lists can be seen as one.

The main reference for it was the corresponding chapter in Learn You A Haskell For Good [2] and a blog post relating Zippers and Comonads [5].

Definition

Zipper is a data structure first published by Gérard Huet [1] and it was designed to enable traversing and updating trees efficiently. It is called Zipper in an analogy to the movement of the zipper from clothes, because it was first applied to traverse trees and it can move up and down efficiently, like the zipper.

When traversing a tree using a zipper, we have the concept of focus which is the subtree rooted in the current node and an information that tell us from which direction we came.

We can define a simple binary tree (which we’ll call Tree) through the definition of a node as follows:

data Tree a = Empty

| Node a (Tree a) (Tree a)

deriving (Show)

The node can either be empty or have some content and a left and right children. When we are traversing the tree we want to keep contextual information that allow us to traverse back in the tree.

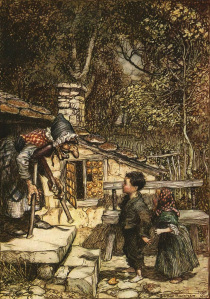

In [2], this context is called a bread crumb, in a reference to the tale Hansel and Gretel in which the kids use bread crumbs to find the way back home.

To be able to return to the previous node, we need to know whether we came taking the right or the left child and also the subtree we decided not to take. This idea is structure as the following datatype that we name Move:

data Move a = LeftMove a (Tree a)

| RightMove a (Tree a)

deriving (Show)A move only allows us to go one step back, but in our case we want to be able to go back to the root of the tree, so we keep a list of moves:

type Moves a = [Move a]Given this, we can define function to go down in the tree, taking the left child (goLeft) or the right one (goRight):

goLeft :: (Tree a, Moves a) -> (Tree a, Moves a)

goLeft (Node x l r, bs) = (l, LeftMove x r:bs)In goLeft, we pattern match a node to get the current element, the left subtree (l) and the right subtree (r). We also need the list of movements bs. What we do is to move to the left node at the same time that we add a LeftMove to our list of moves.

Note that the : operator has lower priority than the function application, so

LeftMove x r:bs is equivalent to (LeftMove x r):bs.

We do an analogous operation for the right move:

goRight :: (Tree a, Moves a) -> (Tree a, Moves a)

goRight (Node x l r, bs) = (r, RightMove x l:bs)Given the current node and a list of moves performed to get there from the root, we can go easily up in the tree:

goUp :: (Tree a, Moves a) -> (Tree a, Moves a)

goUp (t, LeftMove x r:bs) = (Node x t r, bs)

goUp (t, RightMove x l:bs) = (Node x l t, bs)Through pattern matching, we can decide whether we came from a left or a right movement, retrieve the parent node and the other subtree that we didn’t take. With that we can reconstruct the subtree in the level above.

We then conveniently call this tree enhanced with the “breadcrumbs” as the Zipper:

type Zipper a = (Tree a, Moves a)Comonads

While researching about Zippers, I found a blog post from Dan Piponi, relating Zippers to Comonads. It’s really nice because he writing a simple 1-D game of life and Zippers and Comonads are used to implement that in an elegant way.

A Comonad is a structure from Category Theory that represents the dual of a Monad. But for our purposes, we don’t need to know about it.

For his game, the author starts by defining an universe:

data Universe x = Universe [x] x [x]It’s basically a Zipper over a list, where the current element is represented by the second parameter, the first and third parameters represent the elements to the left and to the right of the element in focus, respectively.

One nice instance of this data type is representing the set of integers focusing in one particular element, say 0 for example:

let Z = Universe [-1,-2..] 0 [1,2..]In an analogy to the tree zipper, we can define functions to change the focus back and forth, in this case left and right. The implementation of these moves is straightforward:

goRight (Universe ls x (r:rs)) = Universe (x:ls) r rs

goLeft (Universe (l:ls) x rs) = Universe ls l (x:rs)The author then defines a new typeclass called Comonad which is a special case of a Functor. This structure is available at Control.Comonad but it belongs to the package comonad which is not installed by default, so we need to get it through cabal:

cabal install comonadThe documentation [6] for the Comonad says we need to implement the following methods:

extract :: w a -> a

duplicate :: w a -> w (w a)

extend :: (w a -> b) -> w a -> w bIn the original post [5], extract is called coreturn, duplicate is called cojoin. The =>> still exists and corresponds to extend which has the default implementation:

extend f == fmap f . duplicateSo in order to make the type Universe comonadic, we must make sure it implements Functor. Thus we can do:

import Control.Comonad

instance Functor Universe where

fmap f (Universe ls x rs) = Universe (map f ls) (f x) (map f rs)fmap() basically applies the function f to the entire list that this zipper represents. Now we can provide an implementation for the Comonad typeclass:

instance Comonad Universe where

extract (Universe _ x _) = x

duplicate x = Universe (tail $ iterate goLeft x) x (tail $ iterate goRight x)If we analyze the type description of duplicate and using the wrap analogy for Monads, we see that it’s wrapping an already wrapped element again.

The focus of this instance of Universe is the universe x we received as a parameter. The left list is an infinite list of all universes in which we go to the left of the current state of universe x. The right list is analogous. This forms a set of “parallel” universes.

The extract() function extracts the element in focus of the universe.

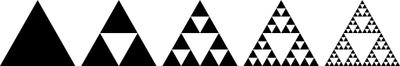

With that definition in hand, we can write a rule to act upon a universe. For the game of life we can work with a universe of boolean values, representing dead or alive. A rule determines the next value of the element in focus x based on its surroundings. We can define the following rule:

rule :: Universe Bool -> Bool

rule (Universe (l:_) x (r:_)) = not (l && x && not r || (l == x))Before applying that, let’s write a printing function for a Universe. Since it is infinite, we can only print a small sample of it. First we define a function to go n positions to the right (if n is positive) or to the left (if n is negative):

-- Move n positions to the right or i position to the left (if i is negative)

shift :: Universe a -> Int -> Universe a

shift u n = (iterate (if n < 0 then left else right) u) !! abs nand then a function to get a sample of len elements to the left of x and len to the right:

-- Return the array [-len, len] surrounding x

sample :: Int -> Universe a -> [a]

sample len u = take (2*len) $ half $ shift (-len) u

where half (Universe _ x ls) = [x] ++ lsand finally a function to convert an array of booleans to a string:

boolsToString :: [Bool] -> String

boolsToString = map (\x -> if x then '#' else ' ')Combining these functions yields simple way to print Universe with an window of size 20:

toString :: Universe Bool -> String

toString = boolsToString . sample 20We can print a sample universe:

toString (Universe (repeat False) True (repeat False))Notice that the rule applies only to the focused object. If we want to apply to ‘all’ elements, we can use the extend or the operator (=>>)

toString $ (=>> rule) (Universe (repeat False) True (repeat False))To run some iterations and print the whole process we can add some boilerplate code:

putStr . unlines . (take 20) . (map toString) $ iterate (=>> rule) example

where example = (Universe (repeat False) True (repeat False))This will print out 20 lines of a Sierpinski Triangle!

Conclusion

This subject was the last chapter of the Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! book which is excellent for newbies likes me. I’m still halfway in the Real World Haskell, which is more heavy-weight, but I also plan to finish it.

Zippers is the first non-trivial functional data structure I’ve learned. There is a famous book by Chris Okasaki, Purely Functional Data Structures, which I’m pretty excited to read.

Once again, going a step further and reading more about the subject, led me to learn a bit about Comonads. I’ve heard about that before and it sounded very complicated, but the its application to the example above is not very difficult.