kuniga.me > NP-Incompleteness > Flood it! An exact approach

Flood it! An exact approach

16 Sep 2012

Flood-it is a game created by LabPixies, which was recently acquired by Google.

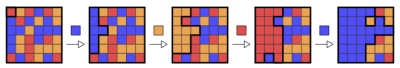

The game consists of a \(n \times n\) board with random colors cells. Let’s call the top-left cell a seed cell and the region connected to the seed cell and with the same color as it, the flooded region. At each round, the player chooses a color for the flooded region which may flood adjacent regions, expanding the flooded region. The final objective is to flood all the board.

In the original game, there are three different sizes of boards: 14, 21 or 28. The number of colors is always 6.

A paper from Clifford, Jalsenius, Montanaro and Sach [1], presents theoretical results regarding the general version of this problem, where the size of the board and the number of colors can be unbounded.

In this post we’ll highlight the main results of their paper and present an integer linear programming approach to solve it exactly.

NP-Hardness

For \(C \ge 3\), the game is shown to be NP-hard even if one is allowed to start flooding from an arbitrary cell. The proof given in [1] is based on a reduction from the shortest common supersequence problem (SCS for short).

Greedy approaches

There are two greedy approaches one might try:

- Pick the color that maximizes the number of cells covered.

- The most frequent color in the perimeter of the current region.

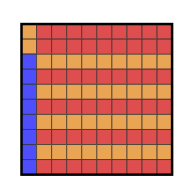

In Figure 2, we have an instance where this strategies can be arbitrarily bad [1]. They use \(n\) colors while the optimal solution is 3.

Approximation algorithms

Surprisingly, the naive strategy of cycling through all colors until the board is colored gives a solution with a value within a factor of the optimal value.

More specifically, if \(L\) is the optimal number of movements and \(C\) the number of available colors, then this algorithm solves the problem with no more than \(C L\) movements. To see why, let \(\{c_1, c_2, \cdots, c_L \}\) be the color sequence of the optimal solution. In the worst case, each cycle covers at least one color in the sequence. Thus, this algorithm is \(C\) approximated.

This can be refined to \(C-1\) observing that the cycle does not need to have the current color of the flooded region.

The authors improve this bound with a randomized algorithm that achieves a \(\frac{2c}{3}\) expected factor.

They also give a lower bound, proving that if the number of colors is arbitrary, no polynomial time approximated algorithm with a constant factor can exist unless P=NP.

Bounds

An upper bound for the number of movements required for solving any \(n \times n\) is given by the following theorem:

Theorem 1. There exists a polynomial time algorithm for Flood-It which can flood any n x n board with C colors in at most \(2n + (\sqrt{2C})n + C\) moves.

Conversely, we can set an lower bound for a \(n \times n\) board:

Theorem 2. For \(2 \le C \le n^2\), there exists an \(n \times n\) board with (up to) \(c\) colors which requires at least \((\sqrt{C - 1})n/2 - C/2\) moves to flood.

That is, we can’t expect an algorithm to perform much better than the one from Theorem 1 for arbitrary boards.

Integer Linear Programming

Let \(C\) be the number of colors and \(k\) an upper bound for the optimal solution. A component is a connected region of pixels with same color, considering 4-adjacency. Two components \(i\) and \(j\) are adjacenct if there exists at least a pixel in \(i\) adjacent to a pixel in \(j\).

We denote by \(N(i)\) the set of components adjacent to component \(i\). Let \(S\) be the set of components and \(m = \mid S \mid\). Furthermore, let \(c_{i}\) be the color of component \(i\).

We define the binary variable \(x_{ct}\) that is 1 if color \(c = 1, \cdots, C\) is chosen at iteration \(t = 1, \cdots, k\) or 0 otherwise. We also define the binary variable \(y_{it}\) that is 1 if component \(i = 1, \cdots, m\) is filled in some iteration \(t\) or 0 otherwise.

For simplicity, we’ll assume that the component of the seed cell has index \(i = 1\).

(1) Objective function:

\[\displaystyle \min \sum_{c=1}^{C} \sum_{t=1}^{k} x_{ct}\](2) For each component \(i\),

\[\displaystyle \sum_{t=1}^{k} y_{it} = 1\](3) For each iteration \(t\),

\[\displaystyle \sum_{c=1}^{C} x_{ct} \le 1\](4) For each component \(i\) and iteration \(t\),

\[\displaystyle y_{it} \le \sum_{j \in N(i)} \sum_{t' = 1}^{t - 1} y_{jt'}\](5) For each component \(i\) and iteration \(t\)

\[y_{it} \le x_{c_it}\](6) For each component \(i = 2, \cdots, k\),

\[y_{i,0} = 0\](7) For the component of seed cell,

\[y_{1,0} = 1\](8) For all component \(i\) and iteration \(t\),

\[y_{it} \in \{0, 1\}\](9) For all color \(c\) and iteration \(t\),

\[x_{ct} \in \{0, 1\}\]Constraint (2) states that we fill a component exactly in one iteration. Constraint (3) says that at each iteration we pick at most one color. Constraint (4) allow us to fill a component only if any of its adjacent components has been already filled (which means it currently has the same color as the seed pixel) and if its color is the same as the chosen color (5) .

Finally, constraints (6)-(9) state the variables are binary and each component starts unfilled except the component of the seed cell.

Computational Experiments

We’ve implemented this model in C++ using the COIN-OR Cbc library. The code is available, as always, on github.

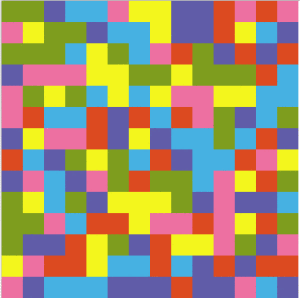

The first task was obtaining “real” instances. I don’t know whether the colors of Flood it! boards are uniformly chosen. Thus, I preferred to take some print screens from the original game and do some image processing to convert it matrices with integer representing colors.

Unfortunately the model is too big if we use \(k\) as the number of components, \(m\). The number of constraints (4) is then \(O(m^3)\) and for the instance in Figure 3, \(m = 127\).

In order to reduce its size, we tried two tricks.

First, we changed our model a little bit to decrease the number of contraints (4). Now, \(y_{it}\) may also be 1 if component \(i\) was covered some iteration before \(t\). Thus, we can rewrite (4) as,

(4’) For each component \(i\),

\[\displaystyle y_{it} \le \sum_{j \in N(i)} y_{j(t-1)}\]But now we need to allow a component to be “covered” if it was covered in a previous iteration, even if the current color does not match. Thus, (5) becomes:

(5’) For each component \(i\) and iteration \(t\)

\[y_{it} \le x_{c_it} + y_{i(t-1)}\]We also need to change (2) equality to \(\ge\) inequalities. Now, note that there are \(O(m^2)\) constraints (4’).

The second trick is based on the assumption that in general, the optimal number of movements is much less than the number of components. Thus, solve the model for increasing values of \(k\) starting with the number of colors until we find a feasible solution.

Even with these changes, we were not able to solve the instance in Figure 3. The 5x5 instance obtained from the first rows and cols of the matrix is solved in 2 minutes using 9 colors.

0 0 1 2 2

3 4 0 0 1

0 0 0 2 4

1 3 3 3 4

3 0 4 0 2Solution:

1 2 0 1 3 0 3 4 2For the 6x6 instance obtained the same way, the solver does not find the optimal solution in an hour.

Conclusion

In this post we gave a brief summary of Clifford et al. paper and then presented a integer linear programming approach to solve instances exactly.

As our experimental results showed, even for the smallest boards (14 x 14) we’re not able to obtain optimal solutions in feasible time.

As future work, we may try devising alternative models or find additional inequalities. Another possibility is to solve this same model using a commercial solver like CPLEX.