kuniga.me > Books > The Innovator's Dilemma

The Innovator's Dilemma

In this book, the late Clayton M. Christensen presents his theory of the Innovator’s Dilemma. The idea is to explain why established companies are sometimes unable to innovate and are overtaken by entrant start ups.

In this review, I’ll try to summarize what I think are the key points of this theory, then provide my review and rating.

Poorly-Managed Companies

A common argument used to justify the failure of companies is that they have bad leadership. The author argues that even companies that are well managed many measures fall prey of the innovator’s dilemma.

The key factor is that well managed companies listen to their users needs. This makes their product well tailored to their existing users, but it misses the ones that are currently not users.

Cost-Structure

The incumbent company operates at a given profit margin and cannot afford to lower it, either because of logistical reasons, but also because a public shared company is accountable to investors who might themselves not agree with investments in low-end markets.

A hypothetical situation provided by the author is helpful: imagine a company wants to avoid the innovator’s dilemma and sets a new division to develop for a low end market. As soon as some urgent need arises on the “high profit” division, people from the “low profit” division are pulled in to help.

The author suggests creating a completely separate small subsidiary that can run with a different cost-structure and avoid such pressures.

Sustaining vs. Disruptive Technologies

Another reason given to why companies fail is that they fail to innovate. The author claims this is not true: well managed companies are able to invest in R&D and come up with improved products, either gradual improvements (incremental change) or some requiring a technological leap (radical change). These innovations, called sustaining technologies, are monotonic improvements: they’re faster, smaller, more efficient, etc.

The author claims that what makes company be left behind are the disruptive technologies. These are technology that are in some dimension worse than the current ones, to a point that most customers (or at least the profitable ones) are not interested in, so the company doesn’t invest in it. However, there might be a niche market that sees value in that technology and that is okay with the downsides.

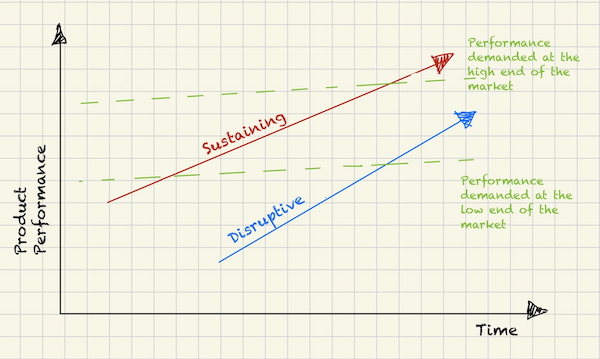

The key is that over time this disruptive technology keeps improving, to a point that most users actually prefer this new technology, but by then the incumbent company failed to capture the market. I found the chart in Figure 1 illuminating.

Disruptive technologies are often cheaper, so by the time they satisfy the basic needs of customers, price becomes a selling point. Another observation from Figure 1 is that companies improve their sustaining so much that is surpasses the need of even the high end customers.

Electric Cars

In Chapter 10 of his book Christensen does a case study on electric cars (EVs), and was wondering if electric cars are a disruptive technology and whether they would displace internal combustion engine cars (ICE).

My review

I had heard of the Innovator’s Dilemma before but I always assumed it meant companies failed to innovate to avoid “eating its own lunch”, that is, launch a new product that competes with their leading one.

The book counters that notion with examples where a company replaced its product with a new improved one. The key is that it was aimed at the same customers as the incumbent product.

Book History

I got this book from a Little Free Library! I had this book on my wishlist since Meta had launched Threads. I thought it could be a case of a company overcoming the Innovator’s Dilemma by launching a competitor to its own products (Facebook and Instagram), but turns out, as discussed above, this is not what the dilemma is about.

Book Structure

The copy I have (from 2000) has about 250 pages, but I found that the bulk of the theory can be obtained from the introduction, which is around 25 pages. The rest of the book is mostly applying the theory to examples.

Electric Cars

I was very curious about the last chapter, since we can check the innovator’s dilemma theory with the benefit of hindsight.

According to this theory, some startup company would come up with a niche use case where electric vehicles may be employed, perhaps golf carts or forklifts. They would be more convenient than ICEs, especially for indoor spaces. Then the technology of electric vehicles would steadly improve to a point where it can capture most of the personal car market.

We can take a look at what happened. By many measures, Tesla was the first company that captured a significant market for EVs. However, it did not follow Christensen’s playbook, quite the opposite: they started targeting the high-end market with a sports car, the Tesla Roadster.

The market for sports car was well served by ICE models, so it’s hard to believe that Tesla provided something that wasn’t being fulfilled by the incumbents. If we only look at the market for electric cars though, the Roadster provided something new: range.

It seems like battery life has always been what held electric cars back. Tesla entered the market as lithium-ion batteries were improving the battery life significantly but were still costly. By starting within the category of expensive vehicles, Tesla was able find users willing to pay the premium for the range.

So if we imagine that the incumbent market was “electric vehicles” and the niche market was “people with money who wanted a EV with high range”, then maybe we can consider this a disruptive technology.

Then we can look at the Toyota prius as a case where the incumbent failed to take that slice of the market. It’s an interesting parallel to make with an example provided in the book, on mechanical vs hydraulic (disruptive technology) excavators. The author mentions an incumbent company that came up with a hybrid of mechanical and hydraulic excavator but never went all in on the disruptive technology.

Survivorship Bias

One thing I’m skeptical about is that there’s a solution for the innovator’s dilemma. The suggestion from the author, as mentioned, is to create a independent subsidiary.

I feel like it’s just impossible to time the market. It just appears that startups did so due to survivorship bias. At any given moment there are multiple startups trying to break into some niche market and failing, disappearing from view.

It’s infeasible for a company to keep branching out into every possible small market and keep doing it continuously until the time is right.

Summary

I found the ideas behind the Innovator’s Dilemma theory novel and congruent. It clarified my (incorrect) preconception of the term. I’m however a bit skeptical of any one solution to the dilemma and that of simple theories for human endeavors. The book, like many books in the humanities (except for history), could have been a lot shorter.

Overall 4/5.